Rural Labor-Intensive Public Works: Impacts of Participation on

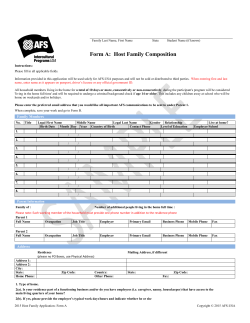

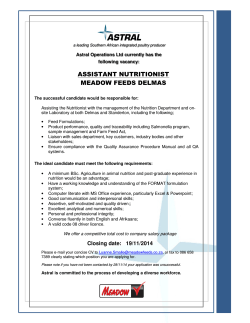

Rural Labor-Intensive Public Works: Impacts of Participation on Preschooler Nutrition: Evidence from Niger Author(s): Lynn R. Brown, Yisehac Yohannes and Patrick Webb Source: American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 76, No. 5, Proceedings Issue (Dec., 1994), pp. 1213-1218 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1243420 Accessed: 13-05-2015 10:46 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Agricultural & Applied Economics Association and Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Agricultural Economics. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Rural Labor-Intensive Public Impacts Nutrition: of Works: on Preschooler Participation Evidence from Niger Lynn R. Brown, Yisehac Yohannes,and Patrick Webb The high incidence of preschooler malnutrition Time Use, Income Generation, and Child continues unabated in many areas of the world. Nutrition Between 1980 and 1990 the number of underweight preschoolers rose from 164 million to Time is a direct input to child nutrition in terms 184 million. The percentage of preschool chil- of child care as well as a complementary input dren below two standard deviations of NCHS to both food and nonfood nutrition inputs. Genreference weight for age in 1990 ranged from eration of income, particularly for the poor, in58% in South Asia and 31% in South East Asia, volves allocation of time to labor activities. to 30% in Sub-SaharanAfrica. A concern is the Low household income requires more housemarginal increase in Sub-SaharanAfrica during hold members, particularly women, to be enthe 1980s [Administrative Committee on Coor- gaged in income-generating activities. This exdination/Sub Committee on Nutrition (ACC/ acerbates already tight female time constraints. SCN) 1992]. While the incidence of poverty Lipton and Ravallion note that "The burden of and malnutrition are highly correlated, income the 'double day'-market labor and domestic growth alone is not sufficient to reverse the labor-is more severe for women. Female agetrends in malnutrition. In Pakistan, despite a specific participation rates increase sharply as 6.3% annual growth rate in GDP per capita be- income falls toward severe poverty; yet so do tween 1977 and 1990 (World Bank), and a the ratios of children to adult women." In the current economic climate of structural marked reduction in poverty (Malik), the improvement in the prevalence rate of under- adjustment, the use of social services such as weight preschool children was less than 1% per health and education often entails both user fees and a complementary time input for seryear (ACC/SCN 1993). Weak linkages between income and improved vice use. Thus, the time demands of female nutritional outcomes have led to a growing fo- child caretakers may conflict with good child cus on nonfood inputs to nutrition. These in- nutritional outcomes. Time in income generaclude mothers education and social service tion activities (translated into higher food exinfrastructure in terms of health care, safe penditures) and time in utilizing health and education facilities improve child nutrition outwater, and adequate sanitation (Thomas, Strauss, and Henriques; Strauss; Alderman comes, but the loss of direct time spent in child and Garcia). However an input that has re- care may worsen nutritional outcomes. The net ceived relatively little attention is time in- effects, therefore, of female employment outside the home are complex, involving a realloputs to child care. cation of time and changing expenditure patterns. A further potential consequence of female Lynn R. Brown and Yisehac Yohannes are research analysts, and is a change in internal household employment Patrick Webb is a research fellow, all at the International Food decision-making processes. The resultant Policy Research Institute. The authors would also like to acknowledge the unfailing suphigher share of female income relative to male port of Lawrence Haddad, and contributions from Harold Aldercan tilt the power base inside the income man, Saroj Bhattarai, Jane Hopkins, Shubh Kumar, Carol Levin household toward women. Evidence indicates and Tesfaye Teklu. Amer. J. Agr. Econ. 76 (December 1994): 1213-1218 Copyright 1994 American Agricultural Economics Association This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1214 December 1994 that income accruing to women, at a constant household income, is more likely to be spent on food and child-oriented goods (Hoddinott and Haddad). There is little evidence to date on the net impacts of female employment outside the home on child welfare levels. A recent study using Ghanaian data found that household calorie availability was adversly affected by external female employment. The net effect of women working, accounting for extra income, was -4.4 calories per-capita per day at the mean (Haddad). This confirmed the results of an earlier Canadian study (Campbell and Horton). Haddad found, however, that the impact was dependent on per-capita expenditure levels. For households below median per-capita expenditure levels where women were engaged in market activities, per-capita calorie availability increased, while for those above median percapita expenditure levels calorie availability decreased. This suggests that, for poorer groups of households, the provision of market-based employment-generating activities for women can increase household calorie availability and potentially improve child nutrition outcomes. This suggestion is not without its caveats. Higgins and Alderman showed that demanding physical labor performed by Ghanaian women had significant negative effects on their own nutritional status. A review of earlier evidence by Leslie did not provide conclusive evidence that maternal employment adversly affected child nutrition. A common policy instrument used to alleviate poverty throughout much of Sub-Saharan Africa is labor-intensive Public Works programs. These programs offer low wages so as to target the poor. The work is physical and energy-intensive, often entailing building infrastructure such as roads, and generally employs both men and women. While work has been done to evaluate the success of these programs in terms of alleviating poverty, little has been done to disentangle differential impacts dependent on the gender of the program participant. Almost nothing is known about the impact of participation on the nutritional characteristics of either the participants or other household members. For example, male participation may raise household income but females may, in turn, have less power in the household decision-making process, resulting in poorer translation of income into household calorie adequacy. The energy-intensive nature of the work may lead to higher energy demands by the male participant, which, given their higher rela- Amer. J. Agr. Econ. tive income share and consequent power position, they are able to realize. Participation by a female may, however, result in a greater share of the household income increase being translated into calories. Thus, while female participation may result in less direct female child care time, it may have a greater impact on household calorie availability and the share being allocated to preschoolers, and consequently yield a net positive impact on preschooler nutrition status. This study will examine the impact of public works participation on the nutritional status of children using household data collected in villages with access to public works programs in Niger. Model The model of choice is the standard Beckerian model (Becker). Optimal household utility is generated from both market-purchased and home-produced goods subject to budget and household technology constraints. Home-produced goods result from the combination of market-purchased goods and household members' time, subject to a technology constraint. One such home-produced good is child health as measured by nutritional outcomes. Let the utility of household h consisting of i members where Mb represents conbe Uh = U(Mb, Oc, Ni), of b market-purchased goods by sumption household h, consumption of c Oc represents home-produced goods by household h, and N, relates to the health of individual i as measured by a nutritional status indicator. The relationship of most concern to us is the production of preschooler health as measured by anthropometric outcomes Ni = h(Ei, Xi, i, •Eh),where N, is the health outcome of individual i who is a preschooler; E is a vector of inputs chosen by the household for individual i, such as mother's time input and nutrients; Xi is a vector of exogenous inputs to health, such as age, sex of i; Li/ is an error term specific to child i which represents unobservable health endowments of individual i, and sh represents unobservable household and community characteristics. The inputs specified in the E vector represent choices made by the household regarding time spent in various activities, including food preparation, consumption of foods, and other goods and services. As such, the level of input use is likely to be correlated with the unobservable error terms in the production function. An instrumental variables technique would permit estimation of a reduced-form child nutrition This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Brown, Yohannes, and Webb Rural Public Works: Impacts on Preschooler Nutrition production function. Estimation of a reduced-form nutrition production function, however, will not indicate how changes in the determinants of the choice of these inputs affect child nutritional outcomes. For example, it will not reveal how changes in labor market activity by household members affects child nutrition outcomes. This effect would be transmitted through changes in household members' time allocation patterns, which may potentially affect the level of other inputs to the child nutrition production function. Given that the objective of this study is to examine the relationship of labor market activity in public works programs to child nutrition outcomes, the methodology will be to use a quasi-reduced form, a hybrid production-demand function.1 Our final child nutrition estimation equation will contain both exogenous and endogenous variables. The latter relate to household public works labor supply, total household labor supply and household per capita calorie availability. All labor variables are at the household level, disaggregated by gender and instrumented. Measures of other nonfood nutrition inputs, such as access to and quality of health care, quality of water, and sanitation, are not available at the household level. Village-level dummy variables, therefore, will be used to control for community-level fixed effects. Data The data is cross-sectional and was collected during 1991-92 from public works programs operating in three rural sites-Banimate, Galmi, and Kalfou Rafi-in Niger (Webb). All the sites have had publics works activities since at least 1987. Banimate is located in a poor northern zone of Niger, close to the Malian border, with very low rainfall. Infrastructure is poor although there is safe drinking water in 1 The ideal methodology would link changes in labor market activity directly to demands for individual inputs which enter into, the nutrition production function. Econometrically, however, this is close to impossible. Many of the input demands will relate to mother's time in a health-related household activity. For example breastfeeding is conditional on mother's time and is also a direct but endogenous input to child nutrition. Estimation of input demand for time in breastfeeding conditional on mother's labor market activity, however, would present a problem as the same price, the mother's wage in the labor market, is relevant for both. It would be difficult to come up with a set of exclusion restrictions that permit estimation of time-related nutrition input demand equations, such as breastfeeding, which include endogenous explanatory variables such as labor supply. 1215 both the wet and dry seasons. The nearest health clinic is a three-hour walk away, as are the nearest market and grain mill. Galmi is a relatively wealthy rural area close to the Nigerian border (ensuring a thriving contraband trade) on a main Niamey to Zinder tarmac road, with a dam providing irrigation for some land. Galmi benefits from schools, a local daily market, and a grain mill. The nearest health clinic is a fifteen-minute walk away, and safe water, a five-minute walk away. Kalfou Rafi, with a rainfall of just 350 mm per year, is very dependent on farming and livestock. Infrastructure and services are limited. The nearest tarmac road is a ninety-minute walk, the health clinic and daily market a thirty-minute walk. There is year-round access to safe water. The public works programs, which are both labor and energy intensive, were all aimed at natural resource protection including soil terracing, reforestation, erosion control, stone terracing, and windbreak planting. All projects use food as the payment medium, with a daily time wage equivalent to 2.25 kg of cereals (typically sorghum or millet), plus additional noncereal commodities such as dried milk, cooking oil, canned meat, and sugar when available. The total number of households surveyed was 275 (74 in Banimate, 126 in Galmi, and 75 in Kalfou Rafi). The survey included modules on demographics, production, assets, employment/ income, time use, food consumption, expenditures, nutritional status measures, and public works project experience. Stratifying the sample into high- and lowpublic-works-participation households showed that high-participation groups were poorer and had an average of three workers per household, compared to one for low-participation households. The average number of days worked per participant was higher for high-participation groups. Women comprised 59% of project participants, providing 61.5% of all public works labor. Most were between the ages of sixteen and thirty-five and were married. For the most part, men were in the same age category. The nutritional indicator chosen for this study is weight for age. Fifty-seven percent of children under six years of age in the sample were more than two standard deviations below the NCHS reference standards. The figure rises to 68% in Banimate and falls to 44% in Kalfou Rafi. Labor days supplied to public works programs are lowest in Banimate, with a yearly mean of 74 days and 60 days for males and fe- This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1216 December 1994 Amer. J. Agr. Econ. Table 1. Variables used in the Analysis: Means And Standard Deviations Variable Mean SD Weightfor age z score Predictedhouseholdpercap. calories Totalpredictedhouseholdmale labordays Totalpredictedhouseholdfemalelabordays Male sharepublicworks* Femalesharepublicworks* Age of child in months -2.35 2,218 514 362 0.14 0.38 35.6 1.65 719 352 192 0.18 0.26 18.5 Sex of child (1 = male) Numberof childrenin householdage < 6yrs Numberof childrenin householdage 6-14 yrs Numberof femalesin householdage 15-65 yrs Numberof malesin householdage 15-65 yrs Numberof adultsover age 65 yrs Sex of householdhead(1 = male) Dependencyratio(persons<15yrs/persons>15 yrs) Household Size Per capitahouseholdassets (valueCFA) 0.53 0.5 3.77 3.90 3.16 2.91 0.3 0.82 1.22 2.32 2.82 1.62 2.13 0.49 0.39 0.8 8.55 4.53 9,907 9,630 Source: IFPRI/INRAN survey 1991-92.2 * Share public works is total household predicted public works days in a year (male/female) as a proportion of total household predicted labor days including public works in a year (male/female). males respectively. In Kalfou Rafi labor days rise, at the mean, to 190 and 215 days per year for males and females respectively. This is the only district where female labor supply to public works is higher than males. Mean daily percapita calorie consumption ranges from 2,148 in Banimate to 3,247 in Kalfou Rafi. The means and standard deviations of variables used in the analysis are reportedin table 1. Results The gender disaggregated instrumenting equations, using predetermined variables to predict public works participation, labor supply to public works, and total household labor supply, are not reported for space reasons. Instruments included asset holdings, household demographic structure, and individual- and community-level characteristics. Coefficients in these regressions had the anticipated signs. For example, the presence of children less than six years of age strongly deterred both female participation and the magnitude of female labor supply to public works programs, but had no influence for men. The results of the per-capita calorie instrumenting equation and preschooler nutritional weight for age regression are shown in table 2. The predicted share of total household public works labor in total labor supply, disaggregated by gender, is included in the per-capita calorie instrumenting equation to measure potential direct impacts of public works employment. While for women the coefficient is positive, for men the reverse is true. This result may be driven by many factors, including but not limited to changes in resource allocation due to women's increased relative income contribution; men paid in food may reduce other intrahousehold transfers resulting in lower food purchases. Within the child nutrition relationship, the coefficient of the share of public works labor variable represents the net effect of several components. It captures income effects outside of calorie availability (hypothesized to be positive for men and women), changes in resource control/allocation (hypothesized positive for women and negative for men), changes in child care time/practices (hypothesized negative for women, zero for men), and the increased competition for calories between participant and child (negative for men and positive or zero for women). In our results the net impact of a rising share of household public works employment for women is positive resulting in an increase in weight for age of children. There is no impact with an increasing share of male public works labor supply. An increase in total household female labor supply also improves child nutrition, whereas for men there is a negative direct impact of increasing total labor supply. This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Brown, Yohannes,and Webb Rural Public Works:Impacts on Preschooler Nutrition 1217 Table2. Results of Calorie InstrumentingEquation and Determinantsof PreschoolerNutrition Log PredCals t stats 8.94 (40.12)** Intercept Male sharepublicworks Femalesharepublicworks Totalpredictedhouseholdmalelabordays Totalpredictedhouseholdfemalelabordays Sex of householdhead(1 = male) Numberof childrenin householdage < 6yrs Numberof childrenin householdage 6-14 yrs Numberof femalesin householdage 15-65 yrs Numberof malesin householdage 15-65 yrs Numberof adultsover age 65 yrs HouseholdSize Dependencyratio(persons<15yrs/persons215 yrs) Age of child in months Age child squared Sex of child (1 = male) Predictedhouseholdper cap. calories Banimate Galmi Adj. R Sq. -0.216 0.123 (1.81)* (1.63)* -0.095 (1.69)* -0.514 -0.121 (9.93)** (4.62)** 0.460 Z score t stats -3.790 (2.93)** -0.475 0.752 -0.001 0.001 0.463 0.121 0.137 -0.243 0.241 0.373 (0.54) (1.74)* (1.86)* (2.06)* (1.54) (1.51) (2.04)* (2.15)* (2.66)** (1.511) -0.067 0.001 -0.416 0.001 -0.984 -0.799 0.143 (2.88)** (3.43)** (2.07)* (1.92)* (1.96)* (2.29)* * significant at 10% ** significant at 1% Conclusion References Fears have been expressed about the impact on child nutrition of participation in public works programs by women; this study allays those fears. For poorer households, increasing the share of public works employment for women has positive impacts on child nutrition over and above its impact of increasing calorie availability, despite potential reductions in direct time inputs into child care. Male participation in public works, however, has no direct impact on child nutritional status, but leads to a reduction in household per capita calorie availability which has a negative impact on child nutrition status. Similarly, increases in female labor supply have direct positive impacts on child nutritional status while for men the opposite is true. Poverty alleviation schemes, such as public works employment programs which have design characteristics that discourage participation by women, may have a lesser impact on reducing preschooler malnutrition. That does not mean, however, that there are no disadvantages to rising female labor supply. This study has taken no account of public works participation by women on their own nutritional status, nor the impact of reduced child care time on other aspects of child welfare. Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub Committee on Nutrition (ACC/SCN). Second Report on the WorldNutrition Situation. Volume 1. Global and Regional Results. Geneva: ACC, 1992. Administrative Committee on Coordination/Sub Committee on Nutrition (ACC/SCN). Second Report on the WorldNutrition Situation. Volume II. Country Trends, Methods and Statistics. Geneva: ACC, 1993. Alderman,H., and M. Garcia. "Food Security and HealthSecurity:Explainingthe Levels of Nutritional Status in Pakistan."Econ. Develop. and Cultur. Change 42(1994):485-507. Becker, G. "A Model of Time Allocation." The Econ. J. 75(1965):493-517. Campbell,C., and S. Horton."Wife'sEmployment, Food Expenditures,and ApparentNutrientIntake: Evidence from Canada." Amer. J. Agr. Econ. 73(1991):784-94. Haddad,L. "The Impactof Women'sEmployment Statuson HouseholdFood Securityat Different Income Levels." Food and Nutr. Bull. 14(1992):341-44. Higgins, P.A., and H. Alderman. "Labor and Women'sNutrition.A Study of EnergyExpenditure, Fertility, and Nutritional Status in This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1218 Amer.J. Agr. Econ. December1994 Ghana." Washington DC: World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper WPS 1009, 1992. Hoddinott, J., and L. Haddad. "Does Female Income Share Influence Household Expenditure Patterns? Evidence from C6te D'Ivoire." Oxford Bull. Econ. and Statist. in press, 1994. Leslie, J. "Women's Work and Child Nutrition in the Third World." World Develop. 16(1988):134162. Lipton, M., and M. Ravallion. "Poverty and Policy." Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 3. J. Behrman and T.N. Srinivasan, eds. Amsterdam: North Holland, forthcoming. Malik, S. "Poverty in Pakistan: 1984/85 to 1987/88." Including the Poor. M. Lipton and J. van der Gaag, eds. New York: World Bank, 1993. Strauss, J. "Households, Communities, and Preschool Children's Nutrition Outcomes: Evidence from Rural C6te D'Ivoire." Econ. Develop. and Cultur. Change 38(1990):231-62. Thomas, D., J. Strauss, and M.H. Henriques. "How Does Mother's Education Affect Child Height?" J. Human Resour. 26(1991):183-211. Webb, P. "Food Security Through Employment in the Sahel: Labor-Intensive Programs in Niger." Unpublished, International Food Policy Research Institute. World Bank. World Development Report 1992. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. This content downloaded from 213.154.74.162 on Wed, 13 May 2015 10:46:05 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

© Copyright 2026