Unraveling learning, learning styles, learning

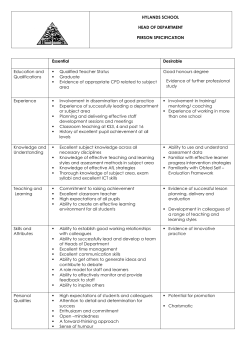

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0040-0912.htm ET 48,2/3 Unraveling learning, learning styles, learning strategies and meta-cognition 178 Lena Bostro¨m School of Education and Communication, Jo¨nko¨ping University, Jo¨nko¨ping, Sweden, and Liv M. Lassen Department of Special Needs Education, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to explore the field of learning, learning style, meta-cognition, strategies and teaching by classifying different levels of the learning process. The paper aims to present an attempt to identify how students’ awareness of learning style and teachers’ matched instruction might affect students’ learning and motivation. Design/methodology/approach – The paper is a conceptual paper in which a theoretical framework built on empirical research was identified by connecting and systemizing different parts of the learning process. Findings – The paper finds that teaching based on individual learning styles is an effective way to ensure students’ achievement and motivation. Awareness of learning styles, it is argued, influences meta-cognition and choice of relevant learning strategies. Consciousness of own improvement provides students with new perspectives of their learning potential. Such positive academic experiences may enhance self-efficacy. Originality/value – The paper provides useful information on unraveling concepts, methods and effects which can aid students, teachers and researchers in understanding, evaluating and monitoring learning, thus having practical implications for promoting lifelong learning, self-efficacy and salutogenesis. Keywords Learning, Learning styles, Self development, Teaching methods Paper type Conceptual paper Education þ Training Vol. 48 No. 2/3, 2006 pp. 178-189 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0040-0912 DOI 10.1108/00400910610651809 1. Introduction This paper is an attempt to explore the field of learning, learning style, cognition, strategies and teaching methods. It is an endeavor to classify and thereby facilitate understanding of the different levels of the learning process in general, but more importantly, the combination of learning styles and strategy choice (Bostro¨m, 2004a, b). While by no means comprehensive, Figure 1 can perhaps illustrate the connections among various concepts involved in learning and strategies. The relationships depicted in Figure 1 are not linear, nor does it show the interrelationships that exist between teacher and students. It, however, attempts to represent the many various elements within a learning process. Teaching is, here, perceived as an activity aimed at guiding the students toward learning and is the foundation for many educational processes. This includes areas as instruction, intentions, inter-subjectivity, interactions, inter-personal activities and processes, actions and praxis (Kroksmark, 1997). A conscious awareness of one’s Unraveling learning 179 Figure 1. The relationships among teaching methods, learning styles, learning strategies, meta-cognition and meta-learning pedagogical platform and its consequences is seen as fundamental for teachers as reflective practitioners (Scho¨n, 1983; Lassen, 2005). Various pedagogical platforms are based on different ideologies, perspectives and methods. In Figure 1 a learning styles platform and a pedagogical platform (for example: lecturing, problem-based learning, Montessori pedagogy, etc.) are depicted. The learning style approach is based on teaching methods that match the individual student’s learning style preference. The later is a fairly stable individual preference for organizing and representing information (Riding and Rayner, 1998). Learning style theory (Dunn and Griggs, 2003) also indicate that this entails a methodical pluralism and argues that students should initially be instructed according to the method best suited for their needs. This can, thereafter, be expanded to include secondary style preferences (Bostro¨m and Lassen, 2005). Learning strategies are seen as conscious or unconscious choices made by teachers or students as to how to process given information and demands of a learning activity (Hellertz, 1999; Kroksmark, 1997). The learning strategies may vary and develop over time. They include learning style, but are broader concepts with various methods (for example: memory strategies, note-taking techniques, and emotional and cognitive strategies). An interesting question is whether one bases one’s choice of learning strategies on one’s individual learning style and whether certain learning style characteristics correspond with certain learning strategies? In this respect meta-cognition, or the ability to think about thinking, may become central. This is awareness and consciousness of the psychological processes involved in perception, memory, thinking and learning (Coffield et al., 2004). While meta-cognition can develop without teaching and education, a learning style pedagogical approach seems to accelerate and develop such reflection. Meta-learning is depicted in Figure 1 as a broader cognitive operation comprised of both how you think and learn about your own learning. The application of this reflective ability may promote abilities for life long learning, self-efficacy and salutogenesis[1] (Bandura, 2003; Antonovsky, 1996). More specifically, with a better understanding of the conditions of learning and more precise knowledge of how choices of strategies affect learning in a positive or negative way, teachers, and ET 48,2/3 180 students’ consciousness of learning may be expanded. Thereby, teachers can perhaps evaluate their programs better, choose appropriate strategies and empower students (Lassen, 2004). Through increased self-awareness of their strengths, student’s self-efficacy, academic competence and resilience may be enhanced (Bandura, 2003; Skaalvik and Bong, 2003; Rutter, 1985). Such aspects may furthermore influence salutogenesis and life long learning (Antonovsky, 1988; Befring, 1997). Salutogenesis is a strength-based conceptualization of indicators promoting health rather than pathology. It attempts to identify factors essential for managing stress, staying well and learning. These are encompassed in a person’s or system’s sense of coherence (SOC) which is defined as: A global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that (1) the stimuli deriving from one’s internal and external environment in the course of living are structured, predictable, and explicable, (2) the resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by these stimuli; (3) these demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement (Antonovsky, 1988, p. 19). The three core components are comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness. Meta-learning-based analysis of one’s own learning can enhance these components through reflection and experience. Even more important may be the pervasive knowledge that one is a learning individual with strengths and possibilities for personal growth and transformation. This becomes a fundamental aspect of one’s SOC. While somewhat influenced by life situations, Antonovsky found SOC to be fairly stabilized by young adulthood (e.g. 25-30 years of age). Educational experiences are, in addition to family and the community, central for developing of this dimension that seems to underlie coping and functioning throughout life. In the learning context several central questions, however, emerge. For example, do learning methods matter? How can one combine learning styles, learning strategies and meta-cognition? Bostro¨m’s (2004a) study identified several very important differences in student’s academic success when learning style methods were applied. These included achievement, retention, attitudes and comprehension. The question arises of whether insight into an individual’s learning style profile may facilitate the development of meta-cognitive understanding and meta-learning for the individual. Pertinent questions were: “What does insight into own learning entail?”; “What exactly is consciousness about learning, and what is an ability to learn how to learn?”; “How can this be linked to terms such as lifelong learning and learning organizations?”; “How can this be interpreted and implemented in the school world?”. These issues need to be addressed so that practitioners can get a clearer perspective of the possibilities and complexity of learning and strategies. These issues are highly pertinent because while the school system’s task is to teach and to transmit knowledge, schools are incapable of supplying students with all the information needed in their lives. Arguably therefore the priority should be to provide students with the abilities and means to search for, find, absorb and use new information that is relevant to their lives. In Scandinavia for example, legislation emphasizes that schools should create the best possible circumstances for enabling students to attain knowledge and provide an environment that encourages a positive attitude toward learning, particularly for those who have had negative learning experiences in the past (Skolverket, 1994; Befring, 2004). This suggests that it should be the school’s goal to help students believe in their own abilities, as well as better understand their own learning. Thus, they can evaluate and monitor their own efforts more effectively. Most learning environments focus on the importance of providing the students with the means, the self-awareness, and skills to learn how to learn. Teachers must, however, first have insight and knowledge into how to provide students with the necessary learning strategies and how to access them. The central concepts describing the learning process are abstract. While they may be easy to use, they are difficult to make tangible. Learning style, learning strategies, study techniques and meta-learning are concepts that sometimes are used without being defined. Rules for usage and concrete examples are missing, and terms often are used synonymously and without accurate delineation. Even more confusing, words like teaching, teaching methods, learning and meta-cognition are at times also used. 2. Learning style and learning strategies The field of learning styles includes more than 70 models with conflicting assumptions and competing ideas about learning (Coffield et al. 2004). In the UK, Kolb’s (1999) Learning Style Inventory (LSI), Honey and Mumford’s (1992) Learning Style Questionnaire, Riding’s (1991) Cognitive Style Analysis (CSA) and Allinson and Hayes’ (1988) Cognitive Style Index are widely used and known. In Scandinavia, Bostro¨m (2004a) chose to use the learning style model presented by Dunn and Dunn (1999). This is a practical model widely applied in schools in the USA as well as in Scandinavia. Learning style is defined as: [. . .] the way each learner begins to concentrate on, process and retain new and difficult information (Dunn et al., 1994, p. 2). Within this model the term “learning style adapted teaching” means applying the methods that correspond to the student’s style as revealed in a self-report learning style analysis (for example using the Productivity Environmental Preference Survey (PEPS) (Dunn et al., 1984, 1991, 2000)). Teaching based on the students’ identified style is thus one way to individualize instruction and is offered as a method to encourage and develop motivation. However, PEPS does not assess a complete range of styles of learning and thinking and other inventories (for example Entwistle’s (1988) Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST), Kolb’s (1999) LSI, Riding’s (1991) CSA, could also be used. While the general consensus is that learning strategies describe the way in which students choose to deal with specific learning tasks (Coffield et al., 2004), many researchers utilize different definitions and add other dimensions to the term. Some see learning strategies a spontaneous choices, learned or conscious patterns, others differentiate between direct or indirect strategies (Kroksmark, 1997; O’Malley and Chamot, 1990; Oxford, 1990; Schmeck, 1988). Hellertz (1999) identified the following learning strategies for students majoring in social science: listening, questioning, talking, thinking, intuition, action, reading, writing and vision as well as combinations of these strategies. She questions whether some strategies (for example: listening or Unraveling learning 181 ET 48,2/3 182 thinking) should be defined as ways of gaining knowledge rather than as learning strategies per se. An important question is whether there exists a difference between the concepts of learning strategy and study techniques. General study strategies (such as “mind-mapping”) can be directly conflicting with the best learning strategy for some students (Bostro¨m, 2004b). In investigating learning strategies for reading, Santa and Engen (1996) emphasized that teachers should develop competence in their students so they can create their own strategies. Tornberg (2000) points out how learning strategies take on a distributive role arguing that student’s previous knowledge, their learning style and the problems they face influence their choice of strategy. She emphasizes the importance of understanding the conditions under which learning takes place and creating a consciousness of this among teachers and students. Her findings indicated that inefficient strategies result in incorrect decisions in the learning process and that it takes energy as well as hard work to replace ineffective strategies with strategies based on an understanding of the individual need. These researchers emphasize the importance of meta-cognition as a basis for building strategies, and as Sadler-Smith (1999) argued the potential of such awareness lies in enabling students to recognize and question long-held habitual behavior. These researchers, further, indicate that individuals can and should be taught to monitor and use various learning styles and strategies. Valid assessment and evaluation is essential for identifying and building out effective strategies (Dunn and Dunn, 1999). For example, in Dunn’s Learning Styles Model (Dunn and Griggs, 2003) learning strategies are included in the methods through which teachers teach and/or learners learn. Methods and strategies which match the different types of learners are, for example, contract activity packages (CAP), program learning sequences (PLS) and multi-sensory instructional packages (MIP). CAP is an instructional strategy that allows motivated people to learn at their own speed, with their best perceptual strength and reporting their knowledge the best way. PLS is a method for individualizing instructions. The content can be learned in small steps without direct supervision. The objectives range from simple to complex ones. MIP present and review the content through visual, auditory, tactual and/or kinaesthetic instructional strategies. This is a self-contained teaching resource that enables students to master a set of objectives by beginning with their strongest perceptual modality and reinforcing learning with their secondary or tertiary strength. The individuals who participated in the Bostro¨m’s (2004a) study were trained in these approaches in order to match their different perceptual learning preference. For example, dramatization and field studies were used for students with kinaesthetic preferences and lecturing was used for auditory students (two components of the MIP). CAP seems to apply better for students with strong internal motivation, internal structure and several prominent learning “senses” (Dunn and Griggs, 2003). While the Dunn and Dunn model can be criticized (see Coffield et al., 2004) with regard to its broad basis and its assessment inventories, the attempt to concretize and systematically apply knowledge about learning style and strategies gives students, teacher and parents a pragmatic means of individualizing education. Based on Bostro¨m’s (2004a) findings, we believe strategies are neither totally fixed nor flexible and that teachers can both build on existing strengths and develop additional competencies for their students. In Bostro¨m’s study students found learning style-based methods to be important aspects of their learning process and were able to use the examples of strategies given to them as well as developing new strategies of their own. However, the question of the connection between choice of strategies, use of strategies, and successful learning was also important. In a sense this may be a “chicken-and-egg” question? Is a student successful because of the strategies he/she chooses, or does a student who is successful in school use the most suitable learning strategies simply because she or he is learning successfully? Further research is required to disentangle these complex relationships. 3. Meta-cognition, meta-learning and teaching By making students aware of which strategies can be used for different tasks and then letting them try out what works best for them, one can assist them by providing a framework for meta-cognition based on assessment and encouraging students to take active initiatives in their own learning process. Being aware of one’s own thought process, how you go about problem solving, decision making and interpretation of the written word are some examples of the activities involved. Since learning uses the self as the subject reflection is a prerequisite for, as well as a result, of learning. Empirical research shows that students who were able to identify and define own learning, were able to influence their learning process, for example Bostro¨m’s (2004a) qualitative results indicated that such students: firstly, made more precise demands on teachers, their school and their education; second, reflected on and understood their own learning, thus enabling them to do their homework, solve problems and better sort through the flow of information; and third, better understood the structure of the school system making it easier for them to participate actively. Taking control of one’s own learning is directly related to self-efficacy. Reflection on one’s thinking about learning leads to a consciousness of learning which may lay the groundwork for meta-leaning. According to Stensmo (1997), this process may be either facilitated or obstructed by different types of emotions. The learning process is guided by the response given by the surroundings and by oneself. Stensmo divides meta-learning into at least two different levels: first, “procedure knowledge”, this is knowledge about abilities, strategies and resources that are necessary to complete a task; and second, “knowledge of completion”, this is an understanding that the task is complete, that you have retained the knowledge and how to move on from this point. Ellmin and Ellmin (1999) believe that reflection can occur on several different levels, but is the necessary foundation when experience is converted into learning about learning. If we were to systematically “photograph” our experiences, does this mean we have learned about our own learning? The question then becomes what should be considered as part of the concept of learning. Two examples of different qualities attached to the term are found in the work of Ha˚rd af Segerstad et al. (1996) and Ericsson (1989). Ha˚rd af Segerstad et al. (1996) claim that learning facilitates a change in the individual’s view of his/her surroundings and him/herself as a person. Ericsson’s (1989) view on the other hand is of learning as an Unraveling learning 183 ET 48,2/3 184 internal, active and outwardly invisible process that could lead to a change in behavior. In other words, learning should facilitate changes in ways of being or acting, in changed ways of thinking or feeling. This development can be achieved in several different ways (for example, modeling, insight, habit formation, etc.) of which only one is conscious reflection. Meta-cognition may, but does not necessarily always lead to such a reflective level of learning. Can teaching methods be related to meta-learning? Kroksmark (1997, p. 45) defines teaching as “a clear and well chosen method to convey information that another individual is expected to learn”. Since it is difficult to separate teaching from learning isolating the concept of teaching in this way is not an easy task (Arfwedson, 1998; Kroksmark, 1997). They can be viewed as two sides of the same coin – two integrated entities that are not interchangeable, but make up two parts of a whole. While teaching may lead to learning, learning can take place without teaching. In addition teaching does not necessarily lead to either learning or meta-learning. While these outcomes can be strived for, they must not be taken for granted. They seem to require both a developmental level of the learner which is abstract and also relevant methodological approaches (which expand knowledge and reflection) on the part of the teacher. In this regard we argue that teaching based on the learner’s preferred learning style appears to have greater possibility to facilitate a meta-learning process. 4. Learning, self-efficacy and salutogenesis Learning is connected with education, but learning occurs everywhere, in every age and is life-long. Every child is born with an innate ability to learn and it is a prerequisite for survival and development (Knoop, 2002). While discussions about meta-learning are related to cognitive developmental research, they also have been spurred by the evidence that institutions can reduce or block a student’s motivation for learning. As early as 1969 William Glasser pointed out that school may indeed create deep-rooted feelings in students that they are failures (Johnsen, 2005; Befring, 2004). Skaalvik and Bong (2003) argued that children’s self-concepts are the school’s responsibility. He noted that many children lost motivation and confidence while in school impairing them for life and thwarting their possibilities for life-long learning. It is paradoxical that an institution whose purpose is to promote learning, may sometimes impede it unintentionally. This may be due to the binding and hierarchical nature of traditional school methods that do not take into account the child’s own initiative and progression, but rather focuses on curriculum (Illeris, 2000) at the expense of these things. Even more crucial are the findings that this process may lead to the misconception on the part of some individuals that they cannot learn and that there, therefore, is little reason to make an effort. The opposite is that it is meaningful to invest energy and time on own development. Understanding of one’s learning style and how to apply this to ones’ best advantage seems to be helpful. In this respect, meta-learning can be seen as a belief concerning abilities to perform the behavior needed to achieve desired outcomes. It is a confidence in one’s own abilities and an understanding that one can influence one’s situation in this respect. Having such an internal locus of control has been identified as a personal resilience factor protecting individuals from the impact of stress (Rutter, 1985; Borge, 2003). Knowledge of one’s own uniqueness and of one’s experiences of success when learning style methods[2] are utilized may indeed have broader consequences than academic achievement. The key may be seeing oneself as an individual that can learn and having the ability to monitor this by the use of ones’ preferred learning style or relevant learning strategy. This notion of meta-learning is related to elements of Bandura’s social learning theory and specifically the notion of self-efficacy. This proposes that reflections are key factors in how people regulate and control their lives. Self-efficacy is a flexible concept (Skaalvik and Bong, 2003). The four underlying elements are: (1) registration of previous successes and failures on similar tasks; (2) observation of other’s learning; (3) persuasion from others; and (4) emotional arousal. Moreover, these are always related to specific situations. Results from Bostro¨m’s (2004a) research indicated that students taught through a learning style-based method improved on the variables that correspond with the four elements of self-efficacy outlined above. They registered own achievements, observed that other students learned through different approaches and became more motivated and enthusiastic (affecting arousal). Finally, the overall principles underlying learning style (that all individuals can learn and have specific abilities) seemed to function as forms of verbal persuasion or encouragement. Both the ideology and methods acknowledge the student as a learning individual. While assessment can begin this process, presentation of stimulation through preferred learning style methods can serve as continuous reinforcements. Minimizing stress (by promoting confidence and enthusiasm) can help students keep within their “developmental/learning flow zone” (Knoop, 2002). Through a sufficiently large number of positive experiences in which one can control many aspects of one’s own learning (a meta-learning) students may reframe their self-concept. From seeing oneself as a failure (Glasser, 1969; Befring, 2004; Skaalvik and Bong, 2003), one perhaps registers under which circumstances and in which situations one succeeds. This type of acknowledgement and self-reflection seems essential as a basis for life-long learning (Illeris, 2000). Experiences from specific situations may also have a profound effect on salutogenesis. Becoming aware of one’s learning style gives the individual a basis for comprehending both the impact of internal and external stimuli. Experiencing one’s own achievements indicates that one has resources available to meet the demands that are posed. Finally, understanding the value of learning for one’s own achievement can strengthen the meaningfulness of investing in and engaging in education. Of the three SOC components outlined earlier, meaningfulness seems most pertinent to induce positive pressure towards salutogenesis (Antonovsky, 1988). As evident from the qualitative findings in Bostro¨m’s (2004a) study, the learning style-based approached appeared to initiate search for meaning. From an academic perspective, stimulating the students’ reflections about themselves as learning individuals and how they achieve learning can make their education to a meaningful endeavour. Knowledge about one’s Unraveling learning 185 ET 48,2/3 186 own learning style and the experiences of applying this can truly empower students (Lassen, 2004). 5. Conclusion Bostro¨m (2004a) found positive connections between methods adapted to the students’ individual learning style (an “adaptive learning environment”) and their learning and motivation. It became evident furthermore that learning strategies could be mobilized, developed and utilized in such adaptive learning environments. They appeared to be based on, but also included, learning styles. Meta-cognition seems to be essential for ensuring that learning strategies may be matched with the individual’s preferred learning style. Being able to recognize and evaluate one’s learning style is a key means of reflecting on one’s own thinking processes. Valid assessment and feedback are crucial to this process. This awareness seemed central for monitoring own learning and proactive use of the students’ own strengths. However, an important question is what consequences this may have for students’ and is this phenomenon only central to the school world or does it have general effects on life more general? If the impact is more general then the importance of schooling is much more than simply mastering curriculum requirements. The educational settings can provide individuals with the impetus to build self-efficacy, strengthen salutogenesis and continue learning throughout life. Whether the learning style approach becomes a widespread innovation within Scandinavia depends on the teacher’s willingness to embrace this tradition. Changes can, however, only be implemented when teachers feel this is meaningful for themselves and their students. Knowledge of learning styles, learning strategies and meta cognition in a broader learning context can give teachers tools to identify the individual traits that effectively impact on achievement and give each learner the opportunity to develop through their personal strengths. Implications for teachers include a possible method to meet any legislation requirements of individualized instruction. Furthermore, through this approach, they can stimulate and respect each individual’s intrinsic value. To empower students towards life-long learning, it seems essential to empower teachers with feasible and effective methodological approaches. Developing teachers’ knowledge of learning styles and learning strategies is a key means by which this can be achieved. Notes 1. Antonovsky coined the term “salutogenesis” in 1979. It is derived from salus which is Latin for health and well-being. In the medical field a salutogenic model focuses on the causes of global well-being rather than the the causes and origins of diseases of specific disease processes. In this paper the concept is transferred and applied to the learning domain. 2. Learning styles methods are defined as methods that match an individual’s learning styles preferences. References Allinson, C.W. and Hayes, J. (1988), “The Learning Styles Questionnaire; an alternative to Kolb’s Inventory”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 269-81. Antonovsky, A. (1988), Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well, Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, CA. Antonovsky, A. (1996), “The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion”, Health Promotion International, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 11-18. Arfwedson, G. (1998), “Undervisningens teorier och praktiker” (“The theories and practical applications of teaching”), Didactica, Vol. 6. Bandura, A. (2003), Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control, Freeman & Co., New York, NY. Befring, E. (1997), Oppvekst og læring. Et sosialpedagogisk perspektiv pa˚ barns og ungs vilka˚r i velferdssamfunnet (Development and Learning. A Socio-pedagogical Perspective for Children and Youth’s Conditions in a Welfare Society), Det Norske Samlaget, Oslo. Befring, E. (2004), Skolen for barns beste. Oppvekst og læring i pedagogisk perspektiv (Schools for Childrens’ Best. Development and Learning in a Pedagogical Perspective), Samlaget, Oslo. Borge, A.I.H. (2003), Resiliens – risiko og sunn utvikling (Resilience – Risk and Healthy Development), Gyldendal Akademisk, Oslo. Bostro¨m, L. (2004a), “La¨rande & Metod. La¨rstilsanpassad undervisning ja¨mfo¨rt med traditionell undervisning i svensk grammatik” (“Learning and method. Research concerning the effects of learning-style responsive versus traditional approaches on grammar achievement”), doctoral dissertation, School of Education & Communication, Jo¨nko¨ping University and Helsinki University, Jo¨nko¨ping and Helsinki University, Helsinki. Bostro¨m, L. (2004b), “La¨rande och strategier” (“Learning and strategies”), Didacta Varia, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 73-81. ¨ Bostrom, L. and Lassen, L. (2005), “Læringsstil og Læringsstrategier. Skitse til udredning av begreber, metoder og effekter” (“Learning and learning strategies: an attempt to outline concepts, methods and effects”), Kognition & Pædagogik, No. 56, July, pp. 44-65. Coffield, F., Ecclestone, K., Faraday, S., Hall, E. and Moseley, D. (2004), Learning Styles and Pedagogy. A Systematic and Critical Review, Learning & Skills Research Centre, London, available at: www.lsrc.ac.uk Dunn, R. and Dunn, K. (1999), The Complete Guide to the Learning Style In-service System, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA. Dunn, R. and Griggs, S.A. (2003), Synthesis of the Dunn and Dunn Learning Style Model: Who, What, When, Where, and So What?, Center for the Study of Learning and Teaching Styles, St John’s University, New York, NY. Dunn, R., Dunn, K. and Perrin, J. (1994), Teaching Young Children through Their Individual Learning Style, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA. Dunn, R., Dunn, K. and Price, G.E. (1984), Productivity Environmental Preference Survey, Price System, Lawrence, KS. Dunn, R., Dunn, K. and Price, G.E. (1991), Productivity Environmental Preference Survey, Price System, Lawrence, KS. Dunn, R., Dunn, K. and Price, G.E. (2000), Productivity Environmental Preference Survey, Price System, Lawrence, KS. Ellmin, B. and Ellmin, R. (1999), “Att go¨ra la¨rande och ta¨nkande till skolkultur” (“To make learning and thinking into culture in school”), Skolva¨rlden, No. 6. Entwistle, N.J. (1988), Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST), David Fulton, London. Unraveling learning 187 ET 48,2/3 188 Ericsson, E. (1989), Undervisa i spra˚k. Spra˚kdidaktik och spra˚kmetodik (Teaching in Languages. Didactic and Methodical for Languages), Studentlitteratur, Lund. Glasser, W. (1969), Schools without Failure, Reality Therapy Institute, Los Angeles, CA. Ha˚rd af Segerstad, H., Klasson, A. and Tebelius, U. (1996), Vuxenpedagogik – att iscensa¨tta vuxnas la¨rande (Pedagogy for Adults. To Produce Learning for Adults), Studentlitteratur, Lund. Hellertz, P. (1999), “Kvinnors kunskapssyn och la¨randestrategier. En studie av tjugosju kvinnliga socionomstuderande” (“Women’s approaches to knowledge and their learning strategies”), doctoral dissertation, Department of Behavioural, Social and Legal Sciences, ¨ rebro University, O¨rebro. O Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1992), The Manual of Learning Styles, Peter Honey Publications, Maidenhead. Illeris, K. (2000), Læring (Learning), Gyldendal Akademisk, Oslo. Johnsen, B. (Ed.) (2005), Socio-emotional Growth and Development of Learning Strategies, Unipubforlag, Oslo. Knoop, H.H. (2002), Leg, Laring & Kreativitet (Play, Learning and Creativity), Aschehough Dansk Forlag, København. Kolb, D.A. (1999), The Kolb Learning Style Inventory.Version 3, Hay Group, Boston, MA. Kroksmark, T. (1997), “Undervisningsmetodik som forskningsomra˚de” (“Teaching methodology as research”), in Uljens, I.M. (Ed.), Didaktik (Didactic), Studentlitteratur, Lund. Lassen, L. (2004), “Empowerment som prinsipp og metode ved spesialpedagogisk ra˚dgivningsarbeid” “Empowerment – principle and method in special education”), in Befring, E. and Tangen, R. (Eds), Spesialpedagogikk, Cappelens Akademiske Forlag, Oslo, pp. 115-29. Lassen, L. (2005), “Five challenges in empowering teachers”, in Johnsen, B. (Ed.), Socio-emotional Growth and Development of Learning Strategies, Unipubforlag, Oslo, pp. 229-46. O’Malley, J.M. and Chamot, A. (1990), Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Oxford, R. (1990), Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know, Newbury House, Rowley, MA. Riding, R. (1991), Cognitive Styles Analysis, Learning and Training Technology, Birmingham. Riding, R. and Rayner, S. (1998), Cognitive Styles and Learning Strategies. Understanding Style Differences in Learning and Behaviour, David Fulton, London. Rutter, M. (1985), “Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder”, British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 147, pp. 598-611. Sadler-Smith, E. (1999), “Intuition-analysis style and approaches to studying”, Educational Studies, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 26-38. Santa, C.M. and Engen, L. (1996), La¨re a˚ la¨re. Prosjekt CRISS. Content Reading Including Study System, Randaberg Trykk, Stavanger (Norwegian version). Schmeck, R.R. (1988), “An introduction to strategies and styles of learning”, in Schmeck, R.R. (Ed.), Learning Strategies and Learning Style, Plenum Press, New York, NY. Scho¨n, D. (1983), The Reflective Practitioner, Temple Smith, London. Skaalvik, E. and Bong, M. (2003), “Self-concept and self-efficacy revisited”, in Marsh, H.W. and Craven, R.G. (Eds), International Advances in Self Research, Information Age Publishing, New York, NY, pp. 67-89. Skolverket (1994), La¨roplan fo¨r det allma¨nna skolva¨sendet, LPO/LPF 94, (Swedish National Curriculum Guidelines), Liber, Stockholm (steering documents). Stensmo, C. (1997), Ledarskap i klassrummet (Classroom Management), Studentlitteratur, Lund. Tornberg, U. (2000), Spra˚kdidaktik (Didactic in Languages), Gleerups, Malmo¨. Further reading Scho¨n, D. (1993), Instructions of Students with Severe Disabilities, Macmillan, New York, NY. To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: [email protected] Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints Unraveling learning 189

© Copyright 2026