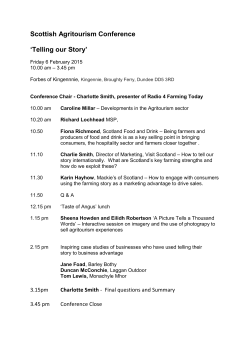

Case Study