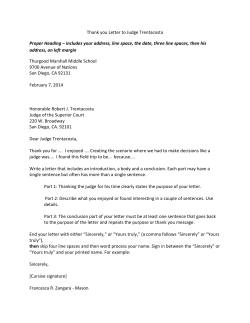

Represent Yourself in Court How to Prepare & Try a Winning Case