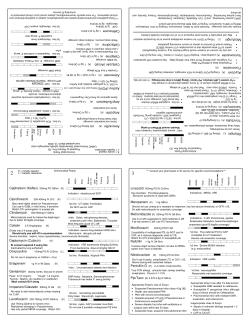

Synthesis and Evaluation of Acridine and Acridone Based Compound as