James Gillray

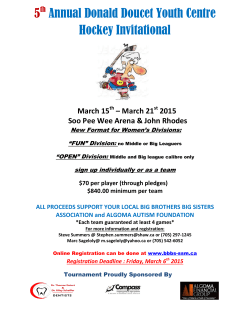

12 Muses Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 26 March–21 June 2015 Up close and extremely personal The themes depicted in these works by the father of political cartooning are very relevant today, even if the subjects are two centuries old, as Paula Weideger reports from Oxford. P Y L A D E S A N D O R E S T E S , 1 7 9 7 . C O L O U R E D E T C H I N G . A L L I M A G E S © C O U R T E S Y O F T H E WA R D E N A N D S C H O L A R S O F N E W C O L L E G E , O X F O R D / B R I D G E M A N I M A G E S Muses / Anne Summers Reports T HE MEN WEAR BREECHES and buckled shoes, the women floor-dusting skirts and ostrich- plumed hats. Yet the handcoloured engravings created by James Gillray (1756–1815) remain among the most ferocious and artistically powerful political caricatures we have. The cast has changed and their get-up with it, but their relevance often has not. Take, for example, his 1797 reverse-take on Midas, the legendary ancient king who turned everything he touched into gold. This is not an entirely random choice: the caricature is one of almost 60 on view in “Love Bites” at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, a show marking the two-hundredth anniversary of the London-born political cartoonist’s death. Prime Minister William Pitt, pointy-nosed and weakchinned, sits spread-eagled on the Bank of England, a prettily upholstered commode. Pitt’s enormous torso is swollen with so many gold coins that they push into his mouth where he vomits them out. As they fly into the air, the gold pieces turn into paper money, as do the ones he shits out below. We are no longer on the gold standard, yet what a clear explanation this is of post-2007 quantitative easing. Although many of his caricatures are densely detailed, Gillray worked fast. He produced about a thousand etchings and some 400 drawings. Many of the latter, done towards the end of his life, are hair-raising, both for their wildness and beauty. Three of them are standouts in “British Drawings”, a companion exhibition at the Ashmolean. “Love Bites” is displayed in a single large space with a tall divider down the middle providing more hanging space. Vertical surfaces are painted in such sweet colours favoured by the Georgians as raspberry pink and robin’s egg blue. The framed caricatures are clustered together according to themes chosen by curator Todd Porterfield, among them “Kisses”, “Courting” and “Marriage”. To say this is misleading understates. For Gillray the personal was political centuries before feminists made this their credo, but in his case this was because everything was political. He targets love, marriage and motherhood; grandmothers and kids, too. In one etching (not on view) French V E R Y S L I P P Y W E AT H E R , 1 8 0 8 . H A N D - C O L O U R E D E T C H I N G Revolutionary grandmas roast babies on spits while tykes on the floor gorge on the entrails of the recently killed. He ridiculed the French Revolution and Napoleon, but also the King and Queen of England and the country’s leading politicians. So, too, were fashion victims, adulterers and art collectors—including, in Very Slippy Weather (1808), buyers of his work. Given the recent tragic killings in France and Denmark, it should be noted that with all this, religion was practically ignored—blasphemy was against the law. Gillray’s The Presentation—or The Wise Men’s Offering (1796), a rare exception, nearly had him up on charges. What with that title, it was not a stretch to connect the baby whose bottom is 51 Muses / Anne Summers Reports A SPHERE PROJECTING AGAINST A PLANE, 1792. HAND-COLOURED ETCHING Gillray is sometimes called a man without a conscience. being kissed with the infant Jesus. This could not be allowed. Even a quick look at a Gillray’s work makes it clear that while he cared greatly about its conception and execution—as well as sales—he otherwise did not give a damn. But wouldn’t you know, that contributed to his fame and fortune. The Prince 52 Muses / Anne Summers Reports T H E G O U T, 1 7 9 9 . H A N D - C O L O U R E D S O F T G R O U N D E T C H I N G into that sore. An attack on the indulgent rich, this is also a portrait of the artist. Gillray is sometimes called a man without a conscience; it may be more accurate to say that he possessed (and was possessed by) an abundance of anger and seemingly unlimited contempt. This did not blur his vision; it made it more acute. There are few biographical facts. His father, who lost an arm as a solider, joined the Moravian Brethren and sent James, age four, to board at their strictly run school. Later he apprenticed as an engraver, then studied art at the Royal Academy schools. Gillray practised his craft fitfully until 1779, when he finally found his métier. Mrs Humphries (single to the end), an already successful Mayfair printer/publisher, accepted his of Wales and leading politicians were frequent customers at the shop of Mrs Humphries, his printer/publisher exclusively. The powerful, it seems, were thrilled to be attacked. Indeed, a young and ambitious George Canning (later Prime Minister), hounded Gillray, asking to be included in his cartoons, since it was a signal that he was important enough to be torn apart. The Gout (1799), with its lush green silk backdrop and cheery yellow cushion in the foreground, creates a shocking contrast with its subject. A large, closeup of a man’s foot shows him to have a huge, red swelling at the base of his big toe—a small, mean furry grey creature with a devilishly pointed tail, claws digging deep in as it makes its way up over the foot, the better to sink its sharp, pointed teeth deep 53 Muses / Anne Summers Reports BANDELURES, 1791. ETCHING cartoonists revere and steal from him, saluting him as the father of them all. Gillray had predecessors, William Hogarth among them. But he was the first to make a living creating political caricatures. And what amazing works they are: technically sophisticated, wildly imaginative and thrillingly beautiful in execution. Two hundred years after he died, his offspring have yet to surpass him. work. Gillray moved in above the shop. Were Mr Gillray and Mrs Humphries lovers? Did he have others elsewhere? In place of answers there is only gossip. What is clear is that the pair were lifelong, devoted companions. As for his character: he drank—a lot—and eventually went mad. He died delusional at home in 1815, looked after by Mrs Humphries. Since his death, Gillray’s work has been in and out of vogue. Ignored during the buttoned-up reign of Queen Victoria, it is prized today. Political SHARE 54

© Copyright 2026