Tips and Tricks for Poster Displays - APAC 2015 v2.pub

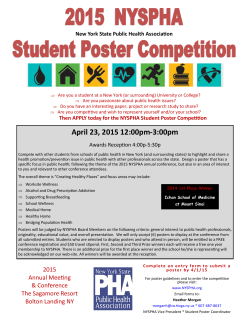

Tips and Tricks for Poster Displays Compiled by: Ma Cope, Quality Improvement Facilitator, Ko Awatea Trish Hayward, Writer, Ko Awatea Alison Howi , Project Manager, Ko Awatea With assistance from: Dr Lynne Maher, Director of Innova&on, Ko Awatea A process for crea on 2 This guide provides advice on the content, layout, design and review of posters for display at conferences. 1. Iden&fy an appropriate conference (Page 3) 6. Dra1 the content and layout (Page 8) 2. Read the conference instruc&ons (Page 3) 7. Get crea&ve: Replace words with pictures, graphs, diagrams, charts and infographics (Page 11) 3. Iden&fy your target audience, key messages and what you’re trying to achieve (Page 4) 4. Logis&cs: ∗ Confirm prin&ng arrangements in advance. ∗ Arrange to transport the poster to the venue safely (Page 5) 5. Write an abstract (Page 6) 8. Decide on design and layout (Page 15) 9. Review and feedback ∗ Use a checklist ∗ Edi&ng and proofreading ∗ Colleague cri&que ∗ Cri&que via social media (Page 17) 10. Print it and present it at the conference (Page 18) 3 First things first Iden fy an appropriate conference The conference you are submi?ng your poster to is likely to have specific themes. For APAC 2015, the conference themes are: ∗ Value-based healthcare ∗ Co-design ∗ Leadership ∗ High-performing organisa&ons ∗ Transforma&onal change ∗ Knowledge management Make sure your poster fits the themes. Consider also ‘poster e&que e’. Do not submit the same poster to a number of different conferences. Read the conference instruc ons The conference organisers will provide guidelines for posters and poster abstracts. Read them carefully. Focus par&cularly on the criteria that the conference organisers have iden&fied for posters. These will tell you the specific sec&on areas that judges will assess and mark you on. Look to see what guidance is provided. Posters that fail to cover the content s&pulated will lose all the points allocated to the missing sec&on. Table 1 shows an example of poster content guidance from Science Fest 2014. Table 1: Content guidance for Science Fest 2014 Criteria What your answer should cover • Sec&on What was the 1 problem? How was the • improvement ac&vity or area of clinical need iden&fied? Sec&on Why did you do it? 2 What were the goals and outcomes you set out to achieve? Evidence of the problem is clearly iden&fied, e.g. through measurement, research, stakeholder feedback Why this is an important area to address Goals and outcomes Iden&fied measureable, achievable goals at the outset of the project Governance and leadership How was the project led and kept on track to achieve the goals/ outcomes? Improvement methodology What did you do? How was your • Provide a clear descrip&on of the approach improvement ac&vity • Show a logical methodology led, planned and Stakeholder engagement what approach did • Explain the approach taken to involve staff, pa&ents and other you take? stakeholders • Demonstrate how stakeholders were communicated with 4 Sec&on 3 Was it successful? Measurement Show a robust measurement of ac&vity against the iden&fied goals and outcomes Benefits Improve quality and the pa&ent experience Poten&al to improve safety Improved health and wellbeing Improve cost effec&veness of healthcare delivery Poten&al to make CMH a be er place to work Next steps How will this be sustained Poten&al to inform best prac&ce and roll out elsewhere Sec&on 4 Presenta on Eye-catching — a visual statement Readability and clarity of content at 1m distance Per&nent informa&on to convey message Does the poster follow a logical sequence? Is the poster informa&ve/educa&onal? What is your poster trying to achieve? Think about your target audience and your focus. Before you start wri&ng, answer the following ques&ons: ∗ Who is your target audience? ∗ What key message do you want your target audience to take away? ∗ How much knowledge does your target audience have of your subject, your organisa&on and the se?ng and context of your work? ∗ What outcome do you want your poster to achieve? Are you trying to share your work with other professionals in your field, secure funding for further work, or something else? 5 Consider logis cs So ware If you have access to professional design so1ware such as InDesign and Adobe Illustrator, these can be good choices for crea&ng your poster. Microso1 PowerPoint is a good, widely available op&on that many people already know how to use. If you choose to use PowerPoint, you can your graphs in Excel and export them. Other op&ons include LaTeX, Inkscape or OpenOffice Impress. Prin ng Make arrangements to have your poster printed well in advance. Your company, organisa&on or university may have a suitable printer. If you don’t have access to a printer that can print a poster, there are a number of prin&ng companies that offer this service. Check also whether the conference organisers have made arrangements for prin&ng posters or nego&ated a discount with a par&cular prin&ng service. Transporta on If you have to carry your poster with you to the conference, roll it up and transport it in a cardboard tube to prevent it from being damaged. Remember to put your name and contact details on the tube if you have to travel by air in case the poster gets lost. Carry the poster with you on the plane if you can rather than checking it in. 6 Write the abstract To get your poster accepted, you will first need to submit an abstract. Wri&ng the abstract can prove almost as challenging as crea&ng the poster itself for many people! First, carefully read the poster abstract guidelines provided by the conference organisers. These may s&pulate a word limit, acceptable methods of submission, and provide guidance on the content that should be covered in posters. Table 2 shows an example of poster abstract guidelines from APAC 2015. The organisers have set a limit of 300 words for the abstract and specified use of a supplied template for submissions. Table 2: Poster abstract guidelines for APAC 2015 Context and problem Where was this improvement work done? What sort of system/unit/department? What staff/client groups were involved? What was the specific problem or challenge that you set out to address? How was it affec&ng pa&ent/client care? Interven on and methodology Provide a clear and succinct overview of the interven&on. State the improvement science methodology or study design used. Measurement and results How did you measure the effects of your changes? State the analy&cal methods used and the results obtained. Effects of change and adaptability to other se1ngs What were the effects of your changes? How much did the changes resolve the ini&al problem? How did this improve pa&ent/client care? Comment on the adaptability of your work to other se?ngs. Your abstract should not exceed the word limit, should be submi ed using the preferred method, and should clearly show that the content of your proposed poster fits the conference themes and poster guidelines. First, consider the &tle. You may not be able to change it once you submit your abstract, so make sure the &tle you give in the abstract is suitable for use on a poster (see Page 9). Next, dra1 the abstract. Think of your abstract as an advert for your poster. Its purpose is to capture the interest of poten&al readers. It doesn't need to include every detail (people can come and see your poster for that!), but it does need to provide a clear indica&on of the informa&on readers will find on your poster. 7 Wri&ng an abstract can be a challenge. The steps outlined below will help you to put together a succinct, informa&ve abstract. A fic&&ous project created as an exemplar for APAC 2015 is used as an example (Figure 1). 1. Read the poster content guidelines again. They provide you with a ready-made structure and tell you exactly what content you need to include. 2. Focus on the first point in the guidelines. For APAC 2015, it is Context and problem. The guidelines s&pulate exactly what should be covered (see Table 2). Cover all the requested informa&on, but no more: The Painless Procedures project was undertaken in the Delirium Unit of Middlemore Hospital in Auckland, New Zealand, by an interdisciplinary team of surgeons, pharmacists and nurses. Postopera&ve pain management for pa&ents with delirium was inconsistent, resul&ng in poor pain control and delayed recovery. Inconsistencies in pain care were related to varia&on in pain measurement among staff and the type of analgesics used. 3. Repeat Step 2 un&l you have covered each point. That is all that needs to be in the abstract. Figure 1: Abstract exemplar for APAC 2015 The Painless Procedures project: Postopera ve pain management for pa ents with delirium Context and problem The Painless Procedures project was undertaken in the Delirium Unit of Middlemore Hospital in Auckland, New Zealand, by an interdisciplinary team of surgeons, pharmacists and nurses. Postopera&ve pain management for pa&ents with delirium was inconsistent, resul&ng in poor pain control and delayed recovery. Inconsistencies in pain care were related to varia&on in pain measurement among staff and the type of analgesics used. Interven on and methodology The Painless Procedures interven&on comprised an educa&onal package including a poster, an online training module, and a skills workshop for postopera&ve nurses. It was implemented over a one-year period through the unit’s professional development scheme and in new staff orienta&on. Posters were displayed in the unit as a reminder. Change was implemented using a series of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, following Model for Improvement methodology. Measurement and results The project team measured changes in reported staff knowledge and confidence and in levels of varia&on in pain measurement and choice of analgesics. Outcome measures were pa&ent length of stay and pa&ent sa&sfac&on with pain control. PDSA cycles were used to study changes, and sta&s&cal process control charts were used for analysis. Staff reported increased confidence in pain assessment and management for postopera&ve pa&ents with delirium. Consistency in pain measurement among staff increased, and analgesic treatment was standardised. Average pa&ent length of stay reduced from 8 days to 5 days. Pa&ent sa&sfac&on with pain control rose from 35% to 85%. Effects of change and adaptability to other se1ngs Improved staff confidence and consistency in postopera&ve pain management for pa&ents with delirium has improved the quality of care for these pa&ents and enabled earlier discharge home. The quality improvement procedures used in this project can be adapted to other units and healthcare se?ngs. Dra4 your content 8 Refer to the conference instruc&ons and ensure that you organise your content around the sec&ons s&pulated. Make it clear where judges and readers can find the informa&on s&pulated. Table 3: Suggested structure for poster displays – APAC 2015 Context Where was this improvement work done? What sort of system/unit/ department? What staff/client groups were involved? Problem What was the specific problem or challenge that you set out to address? How was it affec&ng pa&ent/client care? Assessment of problem and analysis of its causes How did you quan&fy the problem? Did you involve staff at this stage? How did you assess the causes of the problem? What solu&ons/ changes were needed to make improvements? Interven on Describe the interven&on used with sufficient detail that others could reproduce or adapt it. Methodology (improvement science/research study design) If you used improvement science methodology, describe the methodology chosen (e.g. Model for Improvement, Lean, Pa&ent Experience), why it was chosen and how it was applied. If your study was formal research, describe the study design (for example, observa&onal, quasi-experimental, experimental) chosen for measuring the impact and outcomes. Strategy for change How did you implement the proposed change? What staff or other groups were involved? How did you disseminate your plans for change to the other groups involved? What was the &metable for change? Measurement of improvement How did you measure the effects of your planned changes? Describe the analy&cal methods used and the results obtained. Results Display your results in manner appropriate to the methodology used. If appropriate, account for uncertainty and/or limita&ons (e.g. confidence interval). Effects of changes What were the effects of your changes? How much did these changes resolve the ini&al problem? How did this improve pa&ent/client care? What problems were encountered with the process or with the changes? Lessons learnt What lessons have you learnt from this work? What would you do differently next &me? Adaptability to other se1ngs Based on this experience, what is the main message that you would like to convey to others? Discuss the adaptability of your work to other se?ngs. Declara on of conflicts of interest Who has funded your research; any other compe&ng interests that could be connected with your work. 9 Making rough sec&on dra1s on separate pieces of paper or Post It notes at this stage can help to reduce wordiness and plan your layout. Poster tle The main poster &tle should instantly make it clear what the poster is about. Don’t use acronyms - they carry no meaning unless the reader is already familiar with your work. For example, rather than: The 20,000 Days VHIU collabora ve Try: Caring for very high intensity users in the community Titles should be no more than two lines. Make &tles snappy and a en&on-grabbing. For example, rather than: A collabora ve improvement effort to reduce lower limb amputa on rates for diabe c pa ents Try: Feet for life: Reducing amputa on rates for people with diabetes Rather than: Comparing, contras ng and implemen ng a project scoring system to help improve the likelihood of project success and sustainability Try: False starts and high fliers: How can we learn from improvement projects? Sec on headings Try using sec&on headings to help convey your message. A person strolling past your poster should be able to instantly get a picture of what your poster is about, and headings are the biggest, boldest text on your poster, a1er the &tle. Use them! Look at the table below giving two different approaches to sec&on headings for the 20,000 Days collabora&ve SMOOTH (Safer Medica&on Outcomes on Transfer Home). Table 4: Effec ve use of sec on headings Instead of: Try: Problem Adverse drug events (ADE) at transi ons of care Interven on Systema c pharmacist-led discharge Study design Model for Improvement Measurement Tracking ADE by grade Results ADE prevented and corrected Recommenda ons Adopt SMOOTH at other hospitals 10 Presen ng context Always be clear where the work took place and who the key stakeholder groups are. This informa&on is absent from many posters. Individual names and &tles are not needed, but do provide a clear statement of stakeholders. For example: Clinical representa&ves from the surgical team including the specialist nurse and colorectal surgeon, pa&ents and family members, administra&ve staff and a representa&ve from the IT team par&cipated in the project. Presen ng aims and goals Aims and goals must be clear and measurable. Be specific. For example, if your aim is to increase the numbers of staff coming through training you need to say from x to y. Do not use percentages without a level of detail: they are meaningless unless quan&fied with actual numbers. For example, the sentence ‘We will increase the number of people being trained by 6%’ could mean you aim to train three more people or three hundred more! Presen ng interven on and implementa on Say what you did and how you did it. Include informa&on on what tools or methods were used to make the change. Presen ng measures and outcomes Ensure that your aim/goal has a corresponding measure so that progress/success is visible. If there are mul&ple aims/goals, each must have a corresponding measure. The assessor is looking for evidence that the aim/improvement has been achieved. Think carefully about how you display your measures. If using graphs, make sure there are at least six data points and that there is a clear indica&on of when the work started so the assessor can easily iden&fy the baseline. In addi&on to illustra&ng the measures, clearly describe the resul&ng benefits. Explain the difference the work made. A good way to think of this is in terms of benefits to pa&ents, staff and the organisa&on. A few comments or quotes can be included to illustrate these benefits. For example, a staff member might say that training has completely changed his prac&ce, a pa&ent might comment on having fewer hospital admissions and being able to spend more &me being well at home. The organisa&onal benefit might be reduc&on in errors or costs. References Format references properly according to the guidelines provided by the conference organiser. If no specific guidelines are provided, use a standard referencing system. Numbered styles such as Vancouver are preferable to author-date styles such as APA because they take up less of your word limit. Present references using the same size font as you used for the rest of your main text. 11 Get crea ve! Posters are a visual medium A poster is not a paper. Aim for a total of no more than 800 words. Avoid long blocks of text containing more than 10 sentences, and keep sentences short. The eye does not follow lines of text on posters as accurately as it does in a book or journal. Readers can lose the thread of long sentences, and few people will read long screeds of text. Reduce your word count Try these &ps to minimise text: ∗ Use phrases, sentence lists and bullet points. ∗ Use ac&ve sentences – they’re more engaging and usually shorter than passive sentences. ∗ Cut out words that add no meaning: ‘We repeated the test again a1er three months had passed.’ ∗ Use headings and figure &tles to help convey your message. Use pictures and diagrams A poster should contain at least one picture or diagram. A picture is worth 1,000 words! Think about whether some of your text would be be er replaced with a picture. OR Hand-held echo (HHE) Portable, hand operated, ba ery powered echocardiographs can be used as a valuable tool in screening cardiovascular diseases to assess systolic ventricular func&on and in pa&ents with conges&ve heart failure to guide ini&al treatment. It can be used by individual physicians. The use of HHE was tested as part of the heart failure pathway. Figure 1: Hand-held echos used on ward rounds aid the iden fica on of heart disease If using photographs, ensure that you use high resolu&on images that are large enough to be viewed from a distance. A simple test to check the quality of your image is to paste it into PowerPoint, expand it to the margins of the slide and print it on A4. This will ‘blow up’ your image to a large size and will show you if it becomes granulated when enlarged. If the image isn’t clear, either be mindful of this when choosing the image size in your poster or look for an alterna&ve image to use. This same principle can be used for photographs, images of graphs/charts, diagrams and clipart files. 12 Add a thin, plain and simple grey or black border to make photographs stand out. Crop photos to emphasise the important part. Try searching websites like Flickr and Shu erstock for generic photographs, but make sure they are high enough quality and that you do not breach copyright—you may need to contact the photograph’s owner for permission as well as ci&ng the picture appropriately in your references. Infographics can be an effec&ve and interes&ng way of displaying informa&on visually. Figure 2: Infographic showing the weight of New Zealand’s popula on Source: Science Media Centre (reproduced with permission). Use graphs and charts A poster should contain at least one chart or graph. Use graphs and charts to explain and highlight the key rela&onships between figures/data. Ensure graphs are accurate, placed near accompanying text, and are labelled clearly. Graphs should also be large enough to be read easily. If using tables, make sure informa&on can be read easily and that columns are not too narrow or too long. 13 Give your graphs and figures headings which sum up the content shown and therefore help to communicate your message. For example, rather than: Figure 1: Number of pa ent referrals to POAC Try: Figure 1: Increase in pa ent referrals to POAC Ensure figures, graphs and charts are clear and comprehensible from a distance of one metre. If at least the gist of a figure, chart or graph can’t be understood at a glance, it’s too complicated for a poster. Check that axis labels and axis numbers are clear and legible from one metre. Use sentence case for axis labels, not Title Case or CAPITALS or italics. The seven sins of displaying data 1. The sin of choice If using charts or graphs, choose the type that best illustrates what you want to portray. Less is more. Avoid 3-D or ‘noisy’ graphs where possible. 2. The sin of size Think about what axis scale is being used. Does it make your data look like it’s varying too much, or not enough? 3. The sin of shape Format your graph (&tles, shape, size) in Excel first, then paste it as an image into your poster. This will help maintain the dimensions and quality and avoid distor&on. 4. The sin of over-simplifying Show data over &me wherever possible, rather than aggregated (for instance, show data monthly, rather than annually). 5. The sin of waste Delete unnecessary ink, such as horizontal bars, data tables and other ‘chart junk’: X Background colour X 3-D effect X Grid lines X Inset legend boxes 6. The sin of secrets Annotate your graphs and let them tell the story. What is this axis? When did you implement specific changes? What is the value of the average? 7. The sin of overload Display one set of data on each graph. Think carefully how many of your measures you need to show— what’s most important? 14 Figure 3: Ineffec ve graphs Uninforma&ve &tle adds nothing and wastes words Figure X: Line graph showing loca ons 14 Auckland 12 Auckland 10 Wellington 8 Hamilton 6 Christchurch Dunedin 4 Invercargill 2 Thames 0 15 Wellington 10 Hamilton 5 0 Christchurch yr a u n aJ ilr p A yl r e u J b o tc O Auckland Dunedin Invercargill Thames Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Background colour and grid lines reduce contrast and clarity Figure 4: Effec ve graph Too much data displayed makes comprehension a struggle Unclear axis labels 3-D effect makes it difficult to read graph accurately 15 Design and layout Layout Orienta&on can be portrait or landscape. Check the conference poster guidelines for size requirements. If possible, use A1 (841x594mm) or A0 (1189x841mm). Maintain visual balance: ∗ Aim for a symmetrical layout. ∗ Line up edges of text panels and graphical elements. ∗ Include a good balance of text and graphical elements. Ideally, a poster should contain a mixture of text, charts and/or graphs, and photographic elements. Posters that contain only dense blocks of text are dull for readers and unappealing to assessors, who o1en have to look at between 10 and 50 posters. Aim to include at least one graph and one picture. ∗ Use space effec&vely—don’t cram everything in, and don’t leave swathes of wasted space. Use visual grammar—a graphical hierarchy of heading and text size to help readers iden&fy the most important parts of your poster. English is read from top to bo om, le1 to right. Organise your poster accordingly. Top-to-bo om organisa&on also enables two or more people to read your poster at the same &me without ge?ng in each other’s way. Consider using organisa&onal cues such as sec&on numbers. Figure 5: Symmetrical versus asymmetrical layout A symmetrical design that uses space effec&vely An asymmetrical design that wastes space 16 Font Ensure all the text on your poster is big enough to be legible at a distance of one metre. This includes o1en-overlooked text such as axis labels, axis numbers, figure legends and references. Recommended minimum font sizes are: ∗ 48-72 point for poster &tle ∗ 36-48 point for headings ∗ 18-24 point for main text ∗ 14-16 point for fine print Don’t reduce the size of your font to squash in more text – reduce the amount of text! Choose a font that is easy to read. Use sans-serif fonts such as Arial for the &tle and headings and a serif font such as Times New Roman or Palatino for the main text. Serif fonts are easier to read at smaller font sizes and in blocks of text. Avoid fancy fonts such as Broadway. Avoid unnecessary varia&on in font sizes and styles. Le1-jus&fy text. Colour Use colour to help organise and convey your message. S&ck to a limited number of different colours: one for background, one for text and one as an accent colour. Background colour Use cool, muted colours. Avoid presen&ng text straight on top of a background of fancy pa erns, shimmers, textures, graduated shading or large background graphics. Light, solid-coloured text panels can be used over an a en&on-grabbing (but not overwhelming) background to add interest to your poster without detrac&ng from its readability. Text colour Use a dark colour that sharply contrasts against your background colour. Avoid using light text against a dark background. It is &ring to read. Accent colour Choose a bright, contras&ng third colour to draw the reader’s eye to anything you want to highlight. Use it sparingly for maximum effect. Don’t reduce the impact of your accent colour by was&ng it on decora&ve elements like lines and bullet points – use it for what you want the reader to look at. Be aware that some people are colour blind. Some degree of colour blindness affects around 8% of men (0.5% of women). Red-green colour blindness is par&cularly common. Affected people have difficulty dis&nguishing these colours. Check that your colours print looking the same as they do on screen! Choose a combina&on of colours that complement each other: ∗ Light and dark colours together provide effec&ve contrast ∗ Avoid using only pale colours – they will look washed out and lack contrast, reducing readability ∗ Avoid colours that clash or may look unprofessional – lime green, fluorescents 17 Review and feedback Review Use a checklist to make sure your poster contains all the essen&al elements and avoids common piXalls. Some good checklists are available on the internet. See, for example, Strategic Communica&ons & Planning’s poster checklist at h p://www.bandwidthonline.org/howdoi/091023%20Poster% 20Checklist.pdf. Feedback Get a colleague with a sharp, fresh pair of eyes to check your poster over for typos, errors, lack of clarity, poor grammar or spelling mistakes. Ask colleagues to cri&que your poster. To get the most honest feedback, allow people to look over the poster while you are not present. Supply them with Post It to s&ck comments onto the poster. Load your poster onto social media sites such as Flickr and Tumblr to invite comment from colleagues and contacts in other organisa&ons and from the general public. 18 Presen ng your poster Read the informa&on provided by the conference organisers. There may be important informa&on about: ∗ facili&es and condi&ons at the venue for displaying posters ∗ hanging facili&es provided (or not provided!) ∗ &mes posters need to be mounted and removed ∗ &mes presenters may or may not a end their posters ∗ handouts and other suppor&ng informa&on/gimmicks/gi1s/samples etc. you may offer readers. Ensure you bring materials to hang your poster. Bring along business cards and adequate supplies of any suppor&ng informa&on to distribute to interested readers. Ensure that you are as well-presented as your poster! Be professional in dress and manner. Stay close by your poster, but be careful not to obstruct the view of readers or passers-by. Give some thought to what you want to say about your work to readers before the poster session. Plan two or three interes&ng points to make to introduce your poster and sum up what you did, what you found and the difference your work made. Avoid rambling to such an extent that you bore people or hinder them from actually reading your poster. Simply introduce your work as planned and be available to answer any further ques&ons that develop. Remember, too, that most people’s favourite subject is themselves. Ask them one or two ques&ons about their work to get them engaged! Useful resources 19 Resources This guide has been developed from the following resources. We gratefully acknowledge all sources used. Purrington, C.B. Designing conference posters. Retrieved 2014 July 9, from h p://colinpurrington.com/ &ps/academic/posterdesign Hess, G., Tosney, K. & Liegel, L. Crea&ng effec&ve poster presenta&ons. Retrieved 2014 May 22, from h p://www.ncsu.edu/project/posters/ Block, S. Dos and don’ts of poster presenta&on. Biophysical Journal. 1996 Dec; 71: 3527-3529. Penn State University. Scien&fic posters. Retrieved 2014 July 9, from h p://www.wri&ng.engr.psu.edu/ posters.html Munter, M. & Paradi, D. Guide to PowerPoint. Pearson Pren&ce Hall; Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2007. Wilkinson, I. Super seminars, legendary lectures and perfect posters: The science of presen&ng well. AACC Press; Washington, DC: 1998. Bern Dibner Library of Science and Technology. How to create a research poster. Retrieved 2014 July 9, from h p://poly.libguides.com/posters Eggart, M.L. Effec&ve poster design for academic conferences. Retrieved 2014 July 9, from h p:// www.ga.lsu.edu/Effec&ve%20Poster%20Design%20for%20Academic%20Conferences.pdf Strategic Communica&ons & Planning. Poster checklist. Retrieved 2014 July 9, from h p:// www.bandwidthonline.org/howdoi/091023%20Poster%20Checklist.pdf Dowman, M. How to give a poster presenta&on. Retrieved 2014 July 18, from h p://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ ~mdowman/mike_dowman_how_to_give_a_poster_presenta&on.html Science Media Centre. Bulk of the na&on. [Infographic]. Retrieved 2014 July 22, from h p:// www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/wp-content/upload/2011/12/SMC-obesity-final-A4.png Special thanks also to Dr Lynne Maher, Director of Innova&on, Ko Awatea, for her invaluable input.

© Copyright 2026