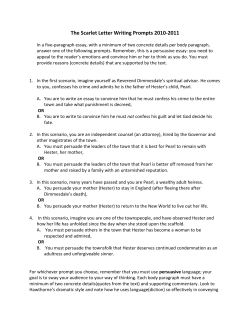

AP World History Teacher's Guide