Conceptualizing Hosts as Participants in International Service

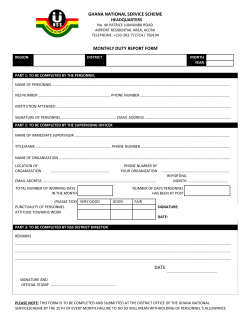

Struggles for Mutuality: Conceptualizing Hosts as Participants in International Service Learning in Ghana Katie MacDonald & Jessica Vorstermans worked in volunteer abroad programming for over seven years. Intecordia Canada: small Canadian ISL organization founded by Jean Vanier (http://intercordiacanada.org) “being with” is more important than “doing for” others, that encountering our weakness and vulnerability can be the sources of significant growth and connection and that the journey of learning is best made together Summer of 2013 we sent long answer surveys with the Intercordia mentor to Ghana to be completed with host families who were interested in the research. The community in which the research was done is a rural community where students live with host families and volunteer at local schools for three months (May, June and July). While the community is identifiable due to our partnership with a small, sending organization, all of the data has been anonymized and participants were informed of this. Seven surveys were administered and responses were either recorded by the mentor, or self-reported. Survey respondents were usually the head of household (generally host fathers) but often the entire host family was present. There was a high rate of return of surveys given the size of the community and number of host families that the organization has worked with. Questions asked included themes such as persistent challenges that they found in their work, why they decided to host students, what were their expectations of students, and if they had any recommendations. hosts as participants- as both teachers and learners and whose expectations and motivations should guide programming programs should be based on mutuality – where hosts and students are thought of as equally important host self-identification mu·tu·al·i·ty ˌmyo͞oCHəˈwalədē/ noun noun: mutuality A reciprocity of sentiments Call from host families – the desire for hosts and participants to live with one another, another, learn from one another, and to share daily life. The call for mutuality is not one which ignores the reality of global structures of inequality underpinned by colonialism, racism, sexism, capitalism and so many other hierarchical systems, but rather is one which tends to the ways in which relationships are built within and against these systems. Many of the host families that we talked with were adamant that cultural exchange and learning about the world was one of the key reasons they participated and wanted to host. ISL provides access to privilege and the ways in which that privilege is unevenly distributed along racial and national lines. The ability to host a volunteer not solely as the possibility for mutual exchange but also for the ways in which it may connect hosts to transnational capital in ways they may not have been prior. cultural capital for their children “I wanted to know people from other countries and how they behave. I also wanted to know more about life outside my country. I was hoping that a student in my house would motivate to study harder.” “When you care for them very well, maybe in the future they will remember you and do something for you.” Call to students to embrace the differences in life in Ghana from their lives in Canada; something that in theory is easy to plan to do but in reality is messy and challenging. “Home away from home is not the same as home.” Hosts were specific in their desire to welcome students who would thrive well in their specificities as a family. we would like to know: “whether [students] are friendly, good character, smoke/do drugs, I don’t want someone counter to my social values.” Two ways Intercordia Canada has developed programming throughout the past ten years to attend to hosts as participants in the pre-departure preparation seminars. These are suggestions - there are others. HEADS UP (Andreotti) (http://globalwh.at/heads-up-checklist-by-vanessa-de-oliveira-andreotti/) Students are introduced to a specific method of telling their life story as an important part of building relationship Scenario #1: You have been getting along fine with your host family. You and your host dad enjoy talking with each other and working in the garden. He asks you to go with him to the market on Saturday. While in the market he mentions that his radio is broken and he cannot afford a new one. He points to a radio that he wants and asks if you will buy it for him. It costs $25. When you say no, he is upset and doesn’t talk with you for the rest of the day. The next day you feel that your host mom is cool towards you and the warm, cozy feeling of the first month is suddenly gone. How does this situation affect the participant? How does this situation affect the group? How does it affect the host community? What would a good way to work through this look like? This suggestion for relationship building and mutuality which calls for students to consider and attend to the motivations of their host families as central to programming can be a challenging realization for students who envision their host family as a locus of love and care and not a particular family with particular historical and economical realities. How can we do this well? It’s a process! Different workshops on cultural difference, encounters and reflection are key to meaningful relationships. For both hosts & students! Incorporating practices into ISL programming which encourage students to conceptualize of their hosts as active participants. thank you Katie MacDonald <[email protected]> Jessica Vorstermans <[email protected]>

© Copyright 2026