Alex âDutchyâ Ghesquiere

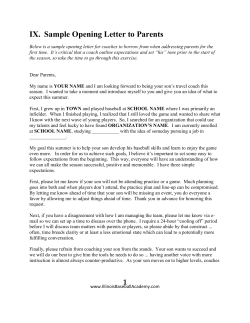

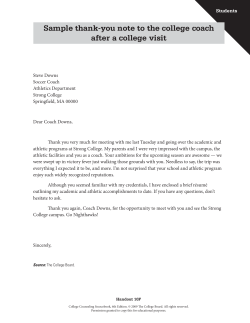

How Alex “Dutchy” Ghesquiere Completed Scandal’s Championship Puzzle Ghesquiere huddles up with his team after a practice and before the start of the World Games in Cali, Colombia. Photo: CBMT Creative BY: JONATHA N NEELEY There’s no place like home. Or is it that there’s nothing like championships? When Alex Ghesquiere, a lanky Belgian who looks a lot taller than his stated 6’1” and is known throughout the ultimate world by his college nickname, “Dutchy,” came on board to coach Washington, D.C. Scandal, the squad was knocking on the door of a national title. But in the women’s division, where nobody had touched San Francisco Fury in seven years, the knob had practically rusted shut. Ghesquiere, however, returned from San Francisco to the east coast city where he grew up with quite the tool collection: appearances with Revolver in the past four straight men’s national final games, including wins in 2010 and 2011, along with gold medals from Worlds in 2010 and 2012 and the World Games this past summer. Not a bad way to say, “I’ve been there before.” Getting there again with Scandal, a new team in an unfamiliar division, would mean both convincing the group they had the pieces to contend as well as guiding them through the assembly of the puzzle. All they needed was a little faith. 27 U S A U lt i m at e Although better known for being pragmatic and focused, Ghesquiere has a lighter, softer side as well. Photo: CBMT Creative Alex Ghesquiere is well known in the ultimate world for having an unmatched ability to analyze players and lay out successful game plans. Photo: CBMT Creative take a moment and some slow breaths and correct your trajectory. The best mentality is one of challenge. It’s the morning of the national final, which doesn’t start until 1:30 p.m. In the lobby of the Homewood Suites, Ghesquiere is leading Scandal through their final meeting before the game. The strategy: use flat marks to stop Fury’s short, inside-out throws; allow long swings, which the Texas wind will make difficult to complete; make them throw deep. Other teams had yet to throw a wrench into the most basic parts of Fury’s attack, said Ghesquiere. If his team could do that, they would win the game. Nobody lays out a game plan like Ghesquiere. Players from every team he has led laud his ability to turn a strategy into a system of inputs and outputs that is at once thorough and actionable – because Seattle Riot had killed Scandal with a trap on the downwind sideline at Labor Day, he told the offense to keep the disc away from that part of the field when the teams met in the national semifinal; when tweaking Scandal’s handler poaches, he emphasized not drifting too far downfield but being able to move as far toward the sideline as possible. His tone when he addresses the team seeps confidence but is devoid of swagger. Knowing both that there is a correct answer and, more importantly, that he has it, is simply a matter of fact. Ghesquiere is naturally inclined to solve puzzles. In “real life,” he is a biomedical engineer that heads research and development for a team that makes glucose meters for diabetics. In his free time, he and girlfriend Kath Ratcliff – also a new addition to Scandal this year – host board game nights at their house in Chevy Chase, Md. Ghesquiere’s favorite game changes whenever he gets the itch for a new challenge, but right now it’s a tie between Family Business and Diplomacy, both of which require players to forge alliances while also aiming to be the last one standing. The popular Pandemic is “cool, but too cooperative for my competitive side,” he says. Getting through to players, for Ghesquiere, is all about WINTER 2013 pushing the right buttons. Before playing Australia in the World Games final, he pulled Mac Taylor aside and told him the game was riding on his match up with Aussie stud Tom Rogacki: if Taylor could force him away from the disc and deny early stall hucks, the United States would win. Taylor, a long-time Revolver teammate of Ghesquiere’s, stewed for a moment before looking back at his coach with a nod and a quiet “I’m ready.” Similarly, with Scandal, Ghesquiere came to understand that Octavia Payne is unstoppable when she is calm but intense; Alicia White is successful when she believes she’s the best player on the field; captain Molly Roy leads best when she doesn’t have to worry about logistics and is encouraged to set an example solely by play. “All players are different,” says Ghesquiere. “What I’ve learned is you have to respect that there are players that need a lot of positive energy and players that you have to fire up by telling them that what they’re doing isn’t good enough. You get to know each player and what works for them.” Ghesquiere prepared Scandal by asking them to visualize their path to the top. At the Chesapeake Invite in late August, he acknowledged the possibility of underperforming in a speech to the team, listing behaviors like tanking, choking and losing their tempers. “When you feel negative mentalities encroaching,” he told them, “take a moment and some slow breaths and correct your trajectory. The best mentality is one of challenge.” Ghesquiere both confronted natural fears and gave Scandal substance to put in their place: optimism, a willing mentality and confidence became the focus. In the week leading up to Nationals, Ghesquiere sent out emails about sleep patterns, sports psychology, and physical preparation. “We are going to win,” he signed them. 28 Ghesquiere started playing ultimate in 1993 while in high school at Sidwell Friends School in D.C. and continued when he arrived on campus at Dartmouth in 1996. He joined Boston’s Death or Glory in 2001, two years after the team’s run of six consecutive championships had come to a halt but with plenty of championship pedigree still on the roster. Ghesquiere – along with Josh Ziperstein and a number of other Boston greats who played during DoG’s twilight – names Billy Rodriguez, who won five consecutive titles with New York, New York before the run with Boson (11 total, if you’re counting), as his biggest leadership influence. Off hand, Ghesquiere estimates that he’s attended thousands of ultimate practices and tournament days, all of which have given him ample opportunity to make mistakes. He blames poor subbing and too long a warm up for Revolver losing the 2009 title game and recalls a college regional final when California, who he coached from 2005 until 2011, lost to Oregon because they stayed in man defense too long. “[Coaching] is a 10,000 hours thing,” he says. “I didn’t step on the field and immediately become a good coach. You have to want to do it and you have to practice and you have to overcome the fact that you’re not necessarily good at it to start. I’ve put myself in situations where I could improve at it and made a real effort. You can work at it by practice, work at it by reading, you can work at it by talking to people. You get better as you go along.” One of his proudest moments as a coach is Cal’s 2010 run to the national quarterfinals, when the team qualified out of the brutal Northwest Region and upset the overall top seed in pre-quarters, despite finishing dead last the year before. “We had no superstars. All the focus was on how we worked as a team,” explains Ghesquiere. Ghesquiere says that while his teams have been hedged by some of the game’s top talent – Beau Kittredge and Taylor with Revolver; the entire World Games roster; and this fall, Payne, Jenny Fey, Sandy Jorgenson, Anne Mercier and White – talent underachieves without leadership and structure. Though he is now strategically removed from Revolver, he points to the team’s 2013 title as evidence of a system with role players who willingly do their jobs to perfection. Adam Simon, who played for Revolver in 2011 and 2012 and helped lead Seattle Sockeye back to the national finals this year, has frequently named Ghesquiere as the best coach he has ever played for – this from a star Ghesquiere asked to focus on catching dumps and throwing swing passes. Without buy-in like that, Ghesquiere asks, how could Revolver have won without Robbie Cahill, Bart Watson and Mark Sherwood, all greats who did not play for the team this year? “You always need talent,” he says, “but ultimate is more than talent. There are so many examples of teams I thought had more talent than Revolver, but they would lose consistently and by fair margins because they didn’t have the right strategy or right mentality, or they weren’t ready to play.” Ghesquiere gives feedback to Mike Natenberg and Beau Kittredge during the U.S. v. Japan match at the 2013 World Games. Japan was the only team to take half on the U.S. In Cali. Photo: CBMT Creative Ghesquiere spent five seasons with Revolver and many more in the Bay Area. 2013 was his first with Scandal, and he didn’t have that much time with the team because of his World Games duties, which included six practice weekends throughout the spring and summer and culminated with a week-long trip to Colombia in July that he and Ratcliff followed up with another week of hiking in Peru. “Scandal to me is very much a work in progress,” he says. “But in the limited time I had with them, I could immediately see that the team needed to become tighter. Getting to know and have faith in each other was a widespread and big-picture thing.” Ghesquiere planned numerous bonding activities throughout the season. For the drive to Virginia Fusion, the team’s final regular-season tournament, he set up a scavenger hunt, giving each car a list of various tasks with corresponding point values – go through a carwash without a car; eat an ice cream cone from the McDonalds dollar menu as fast as possible; snap a group photo with a cow. “One of the most important parts of a team that often gets overlooked is fostering a good mentality,” says Ghesquiere. “Teams that are successful are teams that spend a lot of time outside of pressure situations where they can have a good time and get to know each other outside of ultimate. That’s been a consistent focus for me, and I think that teams have been really clutch in big situations as a result.” Of course, team bonding is not all ponies and rainbows, and like any other coach, Ghesquiere has faced his share of trials. In his first year captaining Revolver, a program that is vocal about how much it values its history and roots, he was part of a leadership group that cut a number of veterans; as coach of the World Games team, he was tasked with running tryouts for the country’s best players – and then cutting the vast majority of them; when he agreed to coach Scandal, he joined co-coach Mike LoPresti, who was on board for last year’s semis berth but had far less big-game experience – and Ghesquiere admits to having a hard time taking direction. But he sees the bearing of burdens as part U S A U lt i m at e You need to have faith in yourself and put yourself in a position where the team trusts you to make those calls. Alex “Dutchy” Ghesquiere celebrates with Washington, D.C. Scandal after winning their first-ever national championship in his first year with the team. Photo: CBMT Creative The 2013 women’s final was a battling of coaching wits. Ghesquiere implemented with Scandal some of the things he learned while coaching the World Games team with Fury’s Matty Tsang this summer. Photo: CBMT Creative of his responsibilities to the team. “As a coach, the team depends on you to make hard decisions. You can’t shrink away from the things that are difficult. You need to have faith in yourself and put yourself in a position where the team trusts you to make those calls.” When Ghesquiere sees something on the field that needs correcting, he will speak sternly or even yell if he thinks it appropriate. But he stresses that his aim is always to bring out the best in his players. He explains, “I’m for positivity. But I’m also for accountability. If someone has made a mistake – a throw they shouldn’t have or they’re positioned wrong – I will go and tell them. But you have to bring them that information in a constructive and positive way, and in a way that every player knows you have faith in them that they’re going to do it right next time. You reach any competitive person with the fact that you want them to win. That’s a common platform to build from.” Scandal is a chance for Ghesquiere to balance his impressive résumé with learning new lessons – to make more strides as a coach. He wants to blend the intensity he has come to expect at east coast practices with the easy-going, teamfirst ethic he found out west, and he says one of his biggest takeaways from the World Games experience was gleaning tidbits on how to manage a women’s team from Fury coach and USA assistant Matty Tsang. “There’s some really exciting new stuff I’d like to try,” he says. “And with a little luck, I’ll have the chance to do it.” Before the final, Ghesquiere gave Scandal one last nudge of belief. Players disagree on whether it was “I got you, we’re winning this,” or “Let’s do this,” but whatever the phrasing, Ghesquiere went around the huddle and, one by one, had each player look another in the eye and say it. The team executed the game plan perfectly, jumping out to an early lead and not looking back en route to a 14-7 win. “It just seemed like the right thing for that moment,” he says. “We needed to get the whole team to buy into what we were going to do so that they believed it was going to work. When the whole team is on the same page, it builds confidence. That’s what Scandal needed going in.” Ghesquiere’s pragmatism sometimes borders on aloofness. After I congratulated him on winning gold in Colombia, he just grinned. “Yeah, I’d say it worked out alright.” At Chesapeake, I asked how the South American vacation was, and he shot me a similar shrug and smile. “Peru is pretty cool.” When pressed about the dynamic with LoPresti, a sensitive subject, he paused before pointing, logically, to the championship. “Seems successful, right?” But he has a soft side too. At a recent D.C. ultimate gathering, he rolled up on a Capital Bike Share bike, laughing because Ratcliff had ridden multiple city blocks on the middle bar. Spend five minutes around the couple, and it’s obvious how much he loves being with her, and he’ll tell anyone he wouldn’t have coached Scandal had she not played. His playful banter with the Revolver contingent of the World Games was a laughing point for the entire group, and after the tournament, he wrote that the best kind of team identity is one of trust and love. Every year, Ghesquiere relaxes with both a ski trip to Jackson Hole and a visit to his parents’ house in Belgium. But perhaps most human about Alex Ghesquiere is that he speaks openly and confidently about his achievements. He does not feign humility; he is proud, but not cocky. That, and his simple but deep love for the game of ultimate. “As a coach, I get nervous and excited. I lose my voice after every game. It still is the highlight of my weekend and the highlight of my fall. Just like players, you come home after a tournament and still feel that everything is muted and quiet compared to the excitement and thrill of the weekend.”

© Copyright 2026