THOMAS WOLBERS

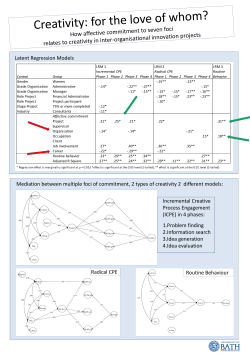

THOMAS WOLBERS Professor, Ageing & Cognition, German Centre for Neuro degenerative Diseases, Magdeburg, Germany THREE PATHWAYS BY WHICH CULTURE CAN INFLUENCE CREATIVITY Three pathways by which culture can influence creativity Thomas Wolbers Creativity is often defined as an idea / a solution / a product that is both novel and useful. But what determines whether a person produces something that others perceive as creative? Most people tend to think that the key factor that determines whether someone is creative is some kind of innate personality trait. For example, Van Gogh was given the ability to produce ingenious paintings, Dostojewski was immensely talented at writing grippling stories, and Einstein’s scientific creativity led to groundbreaking discoveries. Similar mechanisms, of course, are thought to be at play in less famous cases (i.e. the sister who makes beautiful jewellery). This individualistic view, however, overlooks the fact that our behaviour is also shaped by the culture we live in, largely through social norms, contexts that cue them, and motives that drive us to follow, reject or invert those norms. This influence of culture extends to the domain of creativity, where its impact is thought to occur at multiple stages (Figure 1): culture can influence a person’s cognitive abilities and pre ferences, it can affect the process of being creative, and it can have an influence on how the output of a creative process is being judged. CREATIVE PROCESS CREATIVE OUTPUT Cognitive Processing Flexibility Novelty Areas of creative pursuit Persistence Usefullness n io at lu es oc Pr d es an ias b va nt tE te pu on ng O si ut C Preferred Style CREATIVE POTENTIAL CULTURAL INFLUENCE Figure 1: Cultural influences on the creative potential of an individual (left column), on the way creative processes unfold (middle column), and on the evaluation of the creative output (right column) Cultures of Creativities 84 CREATIVE POTENTIAL – CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON COGNITIVE PROCESSING AND THE AREAS OF CREATIVE PURSUITS explained in terms of culture norms and values, i.e. East Asians define the self in terms of social obligations and networks in an interdependent manner, while Westerners see the self as unique and separate from others in an independent manner. As shown in the left column of Figure 1, an individual’s creative potential is largely dependent on his/her cognitive abilities and on how these relate to the area in which one chooses to be creative. Put simply, Van Gogh was a gifted painter, but had he tried to make a career in science, we might not know him today. Current research on the origins of intellectual abilities suggests that about 50 % of our intellectual abilities can be explained by genetic variations (Davies et al., 2011), leaving another 50 % open to external influence. In addition to shaping cognitive processes, individuals may be highly creative in domains that ‘fit’ their cultural values. For example, Korea with its strong cultural valuation of status and interdependence is the world leader in the industry of massively multiplayer simulation games, which involve accruing and using status and maintaining coalitions (The Economist, 2003). Further, at lower levels of analysis (e.g. in work teams), one may see greater creativity in preserving smooth interpersonal relations among individuals from cultures valuing harmony and group cohesion. In contrast, among individuals from Western cultures, more creative ideas about acquiring and maintaining independence and individual freedom may be seen. Put differ ently, cultural differences may not only appear in the extent to which individuals or groups are creative, but also in the specific areas in which their creativity emerges. Individuals may be more creative in some domains than in others because their cultural background values those domains and focuses the individual’s cognitive and motivational resources. There is good evidence that culture can shape basic perceptual processing and that it can influence how people deploy atten tional focus. For example, people in Western cultures tend to focus on salient objects and use rules and categorization to organise the environment, whereas people from Eastern cul tures focus more holistically on relationships and similarities. These findings have been backed up by eye tracking data, which show that when viewing complex scenes, people from Western cultures mainly explore salient local objects, where as people from Eastern cultures explore the background more (Chua, Boland & Nisbett, 2005). Similarly, another study (Hedden et al., 2008) asked subjects to simply judge the length of a vertical line either in absolute terms or relative to a surrounding frame. For Chinese subjects, the relative task was easier, but this advantage was smaller for those that were more acculturated to the US. Such behavioural findings are generally Cultures of Creativities CREATIVE PROCESS – CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON CREATIVE STYLE As shown in the middle column of Figure 1, creativity usually involves two types of processes: the flexibility pathway and the persistence pathway (Nijstad et al., 2010). Cognitive 85 flexibility refers to the ease with which people can switch to a different approach or consider a different perspective, and cognitive persistence represents the degree of sustained and focused task-directed cognitive effort. Importantly, persistence is generally thought to manifest itself in the generation of many ideas in a few categories only – however, when given sufficient time, an individual may eventually move from com bining old elements into mundane ideas to producing increa singly novel yet appropriate ideas → in other words, the same level of creativity may be reached through both pathways! another culture. A famous example is the reception of Ang Lee’s movie Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which was acclaimed by Western film critics for its stylistic innovations, whereas Chinese critics judged it as Ang Lee’s weakest movie, presumably because they had seen many similar movies before (Hempel & Sue-Chan, 2010). Finally, culture can determine the weights people assign to usefulness and novelty – so even if two cultures were to assign the same usefulness and novelty values to a given creative out put, they might judge it very differently in terms of how crea tive it is. For example, as Morris and Leung (2010) note, there is quite some evidence that Chinese culture values usefulness more than novelty, whereas Western culture values novelty more than usefulness (Morris & Leung, 2010). To the extent that culturally divergent social norms are salient, individuals with an Eastern background may be more concerned with usefulness than originality and engage different implicit or explicit standards to downplay or elaborate ideas and insights than their counterparts with a Western background. Cultural values, beliefs, and norms surrounding the individual may predispose him or her to engage in flexible, loose proces sing, to take risks and explore the unknown without fearing to be ridiculed for coming up with distracting and bizarre ideas and insights. Other cultural values, beliefs, and norms may, however, predispose individuals to engage in more incremental, cautious, and analytical processing, to avoid excessive risk and trying to be incremental and cumulative. Specifically, Western cultural norms, with their emphasis on individual freedom and independence, have been shown to steer individuals towards the flexibility pathway whereas Eastern cultural norms, with their emphasis on social connectedness and interdependence, nudge individuals towards the persistence pathway. In other words, cultural norms may actively bias people towards flexibi lity or persistence, i.e. in the way they promote risk-taking vs. cautiousness, being radical vs. incremental etc. In an economi cal context, such differences can have direct consequences for the success of an organisation – for example, “inventions result more frequently from projects with incremental objectives in Japan (66 percent) than the U.S. (48 percent), and less frequently from projects with breakthrough objectives in Japan (8 percent) than the U.S. (24 percent).”(Morris & Leung, 2010) REFERENCES Chua, H.F., Boland, J.E. & Nisbett, R.E. (2005), ‘Cultural variation in eye move ments during scene perception’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 102, no. 35, pp. 12629-33. Csikszentimihalyi, M. (1997), Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Intervention, New York: Harper Collins. Davies, G., Tenesa, A., Payton, A., Yang, J., Harris, S.E., Liewald, D., Ke, X., Le Hellard, S., Christoforou, A., Luciano, M., McGhee, K., Lopez, L., Gow, A.J., Corley, J., Redmond, P., Fox, H.C., Haggarty, P., Whalley, L.J., McNeill, G., Goddard, M.E., Espeseth, T., Lundervold, A.J., Reinvang, I., Pickles, A., Steen, V.M., Ollier, W., Porteous, D.J., Horan, M., Starr, J.M., Pendleton, N., Visscher, P.M. & Deary, I.J. (2011), ‘Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic’, Molecular psychiatry, vol. 16, no. 10, pp. 996-1005. CREATIVE OUTPUT – CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON HOW THE END PRODUCT IS JUDGED: WHEN IS AN IDEA CREATIVE? AND HOW CREATIVE IS IT? Hedden, T., Ketay, S., Aron, A., Markus, H.R. & Gabrieli, J.D. (2008), ‘Cultural influences on neural substrates of attentional control’, Psychological science, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 12-7. A third pathway for cultural influences on creativity is the evaluation of the result. As noted by (Csikszentimihalyi, 1997), creativity lies in the eye of the beholder – it is commonly assessed by a community of experts in a field (i.e. a profession, craft etc.), relative to what is already established in this field. As a consequence, given that there are often large differences in the prevailing ideas and practices between different cultures, a product/idea etc. judged as being very crea tive in one culture might be perceived very differently in Cultures of Creativities Hempel, P.S. & Sue-Chan, C. (2010), ‘Culture and the Assessment of Creativity’, Management and Organization Review, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 415-35. Morris, M.W. & Leung, K. (2010), ‘Creativity East and West: Perspectives and Parallels’, Management and Organization Review, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 313-27. Nijstad, B.A., De Dreu, C.K.W., Rietzschel, E.F. & Baas, M. (2010), ‘The dual pathway to creativity model: Creative ideation as a function of flexibility and persistence’, European Review of Social Psychology, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 34-77. The Economist (2003), ‘Invaders from the land of broadband’, December 11. Available from: www.economist.com/node/2287063. 86

© Copyright 2026