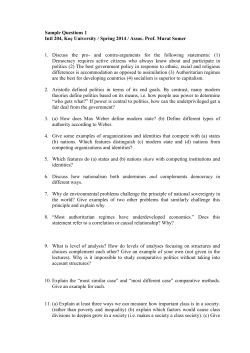

Anarchy is what states make of it