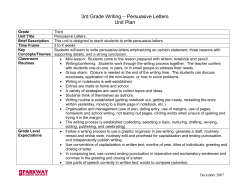

Crafting a Persuasive Speech Press Fountainhead

Pr es s d in he a un ta Fo ht ig yr C op Crafting a Persuasive Speech 222 13 Chapter Overview in he a d Pr es s Chapter 13 • Discusses the Classical Greek and Roman approaches to structuring persuasive speeches. • Explains how to combine classical and contemporary approaches in developing introductions and conclusions for persuasive speeches. • Describes the various organizational patterns for persuasive speeches. Practically Speaking I C op yr ig ht Fo un ta n 1924 at a small YMCA in Santa Ana, California, a small group of people got together to help each other become better public speakers and have a little bit of fun in the process. Over the years, that small group expanded and became a group called Toastmasters International, a non-academic leader in helping people develop oral communication skills. This nonprofit organization now boasts nearly 235,000 members in over 11,700 clubs like the one in Santa Ana that started it all, in 92 different countries.1 Toastmasters begins by using a manual to help members develop certain speaking skills. It focuses on the use of humor, gestures, and eye contact. Once the initial manual is completed members then progress to more advanced manuals that narrow the skill’s focus considerably. Thousands of corporations, companies, and civic organizations encourage their employees and affiliates to participate in Toastmasters because of the practical benefits gained from the group. Toastmasters International also contributes much in the way of community service. They promote youth programs designed around developing oral communication and leadership skills. They support “Gavel Clubs” where they bring speech training inside prison walls. They work with community organizations and businesses to help them tell their story to the community in which they reside. Additionally, they offer short courses on crafting a speech.2 One of the central focuses of the Toastmasters International programs on crafting a speech is organization. In fact, they make it a point to tell people one of the ten most common errors in public speaking is lack of preparation and organization. When you do not organize your thoughts in a logical manner, and then present them to an audience it makes it at best difficult, and at worst near impossible 223 The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking Classical Speech Structure Pr es s for your audience to follow what you are saying and ultimately get anything out of your presentation. Persuasive speeches must be carefully arranged to ensure the speaker achieves their specific purpose. In fact, persuasive speeches were the foremost concern of the Greeks and Romans. The first part of the chapter will discuss the ways in which Classical Greeks and Romans taught students how to construct persuasive speeches. Then, we will discuss how you can incorporate that approach with aspects of the model for developing an informative speech we spoke about in Chapter Ten. Finally, we will offer several different organizational patterns you can use for the various types of persuasive speeches we identified in the previous chapters. un ta in he a d It should come as no surprise that the Greeks and Romans were among the first to break down a speech into its component parts. Today, we use different terminology, but the segments of the speech are essentially the same. It appears the most effective way to organize a persuasive speech has changed very little over the course of the last 2,500 years! But, as the saying goes, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” In this part of the chapter we will discuss the three sections of a persuasive speech as identified by the Greeks and Romans: the exordium, narrative and conclusion. The Speech Exordium exordium C op yr ig ht Fo As we discussed in Chapter Ten, the introduction is your best opportunity to establish a rapport with your audience, something very important in persuasive speeches as your goal is to get them to do or believe the thing which you discuss. This importance was not lost on the Greeks and Romans either, so the best way to understand how to craft an effective introduction to a persuasive speech is to begin with those that gave it a lot of thought. In this section we will discuss introductions using the terminology of the Classics, who called it a speech exordium. We will explain why they saw it as important, and detail what are the elements of an exordium. The Greeks and Romans referred to the start of a speech as the exordium, as they understood it as the place in the speech where you convince an audience to listen to your position. In fact, Quintilian stated that the purpose of the exordium is to prepare the audience to listen intently to the remainder of the presentation.3 One of the ways you accomplish this task is by capturing the interest of the audience and the other is by establishing your credibility as a speaker. A good exordium captures the interest of the audience almost immediately by connecting the topic to something the audience might be interested in. Aristotle argued that this process included an effort to make the audience hold a favorable impression of the speaker and the topic. After you gain their interest with your opening statement using one of the attention-getters we identified in Chapter Ten, you need to begin the case for why the audience should listen to what you the place in the speech where you convince an audience to listen to your position; Latin label for the introduction of a speech 224 Crafting a Persuasive Speech C op yr ig ht Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s have to say on the topic. You do this by demonstrating knowledge of the subject matter. Although an exordium remained one of the most important parts of a speech for the Greeks and Romans, they felt it should not be the first part of the speech you prepare for two reasons. First, Cicero warned his students that it was impossible to effectively introduce arguments yet to be crafted. You may know what you want to say, but until you write it down in order you don’t know how you will say it, or the order in which you will present the points. Essentially, Cicero suggested writing the bulk of the speech before creating the exordium. The second reason classical speakers felt the exordium should be composed last also illustrates a key difference between an introduction for an informative and a persuasive speech. Cicero stated that the quality of the case the speaker presents should determine the type of exordium created. He proposed two ways to begin a speech, although he also pointed out that there are rare situations when exordiums are not necessary—those rare instances do not exist for informative speeches. The first type of exordium Cicero discussed he called an introduction. Cicero understood the introduction, as an exordium that lays out the speaker’s case in plain language so that the audience becomes receptive and attentive. They are often most useful when an audience is confused or illinformed, and the topic is not controversial. Introductions today are often understood as the only way to start a speech, whereas for Cicero they were simply one way to do so. That is why this method of crafting an exordium seems familiar—it’s similar to how we described starting an informative speech a few chapters ago. Cicero reserved the other form of exordium, insinuation for cases made about disputed topics to audiences with animosity toward the topic or the speaker. A common insinuation exordium promises the audience you will be short and to the point when you know they are tired of hearing about the issue on which you are speaking. These work to reduce the reluctance of an audience to listen, and allow speakers to make their case. Unlike introductions, insinuations do not need to unpack information for the audience to relieve confusion, because the audience is already informed—in fact, possibly over-informed!—about the subject matter. Regardless of which type of Ciceronian exordium you might use to begin your persuasive speech, there are various ways to gain the attention of an audience while making them more receptive to your speech by enhancing your credibility. The first way involves stressing the importance of the topic of your speech and connecting it to the lives of the audience. For example, if you deliver a speech arguing to update the technology of a factory in a town, you might also stress the importance of your topic to the community at large, telling them that the plant was outdated and that the plant would close if the technology wasn’t improved and so the expensive update would actually save jobs for the community. Either way, you need to connect the audience to the topic in a personal way that increases the likelihood they will listen to what you have to say. This is something typically not necessary with informative speech introductions because the audience is there to learn something, and thus wants to be there. One final piece of advice offered by the Romans on exordiums is important to note. Cicero believed, as did his Roman counterpart Quintilian, 225 13 introduction one form of exordium where speakers use plain language to lay out their case in an effort to get a confused and ill-informed audience to pay attention insinuation a form of exordium reserved for cases made about disputed topics to audiences with animosity toward the topic or the speaker The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking in he a The Speech Narrative d Pr es s that exordiums must be serious in nature as this lends gravity and importance to the topic of the address. Cicero maintained that when a topic has the support of the audience before the speech even begins, then a rhetor might best eliminate the exordium because it could make the speaker seem condescending. In such situations speakers still previewed their speech, but did away with the elements of the exordium that attempted to raise the interest of the audience. Quintilian additionally advised that if a speaker entertains doubts about the audience’s knowledge of the issue under consideration then they should briefly review the situation in the exordium. Both of these suggestions underscore ways for you to lend gravity to your speech and increase your ethos within the exordium. The Greeks and Romans understood that exordiums are the first impression a speaker makes on an audience, but the last part of the speech to be composed. Their content is driven by the topic and the disposition of the audience toward the speaker, and the goals are to get the attention of the audience, establish a speaker’s credibility, and ensure receptivity to the speaker’s message. Once these goals are accomplished they taught students to move to the body, or what they called the narrative. ht Fo un ta Aristotle argued that the introduction was one of only two elements of a speech, referring to the second component as the argument proper. The Romans taught that the body of the speech that followed the exordium contained three parts: the statement of fact, the argument and the refutation. In this way they expanded Aristotle’s approach to arranging a speech. In this section we will discuss the elements of the narrative of the speech, or what we now call the body, by addressing the three areas identified by the Romans. When we use the term “narrative” today we think of a coherent story, or even fiction. Our understanding of the term differs from that of the classical Greeks and Romans when applied to constructing a speech. For them the narrative of the speech consisted of several parts arranged in a coherent order. They did not provide an exact recipe for that order, acknowledging that each speaking situation called for a different response and thus a need for the speaker to arrange their points differently. The first of these parts they called the statement of facts, an explanation of what the audience needs to know in order to appreciate the main argument of the speech. The statement of facts helps speakers familiarize their audience with the relevant details about their topic. Cicero and Quintilian both recognized that this portion of the narrative might not be necessary all the time, and at other times might be the only part of the narrative required of a speaker. If an audience is familiar with the case you present, then a brief statement of facts might be all that is needed, if any at all. For instance, if you plan to convince the student body at your school that they need to build a new recreation center through an additional student fee, you may not need to explain why since the students might well be aware of the need. When your goal is simply to inform an audience then the statement of facts is the only element of the narrative you need to develop. Here, an audience is confused or ill-informed about your topic and your goal is to convey information to them. The facts of the case are all you need to present an informative speech, C op an explanation of what the audience needs to know in order to appreciate the main argument of the speech yr ig statement of facts 226 Crafting a Persuasive Speech C op yr ig ht Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s as you are not making an argument nor countering any opposition to your point of view. In persuasion, however, arguments flow from the facts of the case—even when they are not explicitly outlined in the narrative by the speaker. The Greeks and the Romans believed that the argument was the core of any speech, and this is certainly true when your purpose is persuasion. The argument, also called the proof or confirmation, is the portion of the speech that validates your position on the issue laid out in the statement of facts. It is, for all intents and purposes, the central idea of your speech laid bare for the audience. Whereas in an informative speech the thesis statement is a one sentence sum of the goal of your speech, the Greeks and Romans taught that in a persuasive speech the argument portion of the arrangement of your speech details all the evidence and claims you make regarding your topic. The argument portion of the speech often contains more than one claim, and choosing the way to organize these claims to maximize your ability to persuade your audience is tricky. The Greeks and Romans both taught their students not to start with their strongest most persuasive claim; rather they suggested that in many cases you should end with it. This allows your argument to end on its highest and best note, rather than a weaker less persuasive point. Quintilian suggested spending more time developing the strongest point than the weaker arguments, which he proposed should be lumped together if at all possible. On the latter suggestion he famously wrote, “They may not have the overwhelming force of a thunderbolt, but they will have all the destructive force of hail.”4 After you organize your claims in the argument portion of your speech, you still must be aware of the opposition. The third component of the narrative part of the speech according to the Classical speech teachers is where you attempt to anticipate opposition to your argument. The refutation, or the response to opposition to your argument, is only relevant for persuasive speeches and even then situational factors largely determine where you place it. For example, if your audience likes the position opposing yours, it might be best to lay out the refutation as reasons not to like the opposition before you even detail your argument. In this instance, moving the refutation to a position immediately following the exordium might be wise. However, when an audience is hostile toward either you or your argument, even Quintilian would encourage you to hold the refutation for as long as possible. The Greeks and Romans believed the refutation is an important part of any speech for two reasons. First, it demonstrates that you thought about and researched the issue on which you are speaking, thus enhancing your own credibility. Second, it makes you appear more objective, making it easier for people to listen to your point of view. In other words, if people don’t view you as partisan about an issue, then they will be more likely to be persuaded by your arguments. Determining the order of the statement of facts, argument and refutation is the first of a two step process. The second step in constructing the narrative involves connecting each to the other, in other words providing the glue that enables your argument to make sense. You can accomplish this by using one of the several different connective statements we discussed in Chapter Ten. Connective statements are common to both informative and persuasive speeches. All told, for the Greeks and Romans the narrative, or body, of a speech is 227 13 argument also called the proof or confirmation; the portion of the speech that validates your position on the issue laid out in the statement of facts refutation response to potential opposition to your argument The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking The Speech Peroration principle of recency d C op yr ig ht Fo the idea that the last message you heard is most likely to be the one you remember in he a speech conclusion If the narrative, or body, is important because it contains the core point of the address, then the conclusion is important because it summarizes that idea for the audience. Aristotle and Cicero both contributed to our understanding of the content and goals of a conclusion, or as they called it, the peroration. Conclusions represent the last opportunity for a speaker to present their case to the audience and leave the audience with something to remember. Think about the last speech that you heard. What do you remember? The evidence? A statistic, perhaps? More than likely, you remember how that speaker finished the speech, the last words spoken. This is illustrative of the principle of recency, or the idea that the last message you heard is most likely to be the one you remember. For this reason it is important to finish a persuasive speech with a bang, and not a whimper. You want the audience to leave knowing what you want them to do or believe and why you want it. Aristotle taught that conclusions accomplish four things. First, they need to leave the audience with a positive impression of you as the speaker. Failing that, it needs to at least leave them with a less than enthusiastic view of your opponent. Second, conclusions need to both augment the force and presence of your arguments while diminishing the power of those that may be offered by your opponent. Third, Aristotle argued conclusions must incite the proper emotions in an audience. Finally, he believed conclusions should restate the arguments and supporting facts central to the speech’s goal. Cicero followed up on Aristotle’s approach by advocating three distinct things speakers could do in their conclusion. First, like Aristotle, he stated speakers should summarize their ideas. This summary should briefly review the statement of facts and take a moment to encapsulate each of the main points the speaker presented. Second, Cicero called for speakers to use the conclusion to cast anyone who disagreed with them in a bad light through emotional appeals. Finally, where Aristotle argued conclusions must incite the proper emotions, Cicero gave the emotion a name: sympathy. He also said that the audience’s sympathy should be toward the speaker and the topic, not one or the other. In fact, in his book De Inventione, Cicero provided quite a number of specific ways to accomplish this (for a few examples, see Table 13.1). un ta peroration Pr es s the most time-consuming and difficult to develop. Placing the three elements of the narrative—the statement of facts, the argument, and the refutation—into the best possible order and making that arrangement seem natural and smooth takes time. Additionally, determining that order is significantly influenced by situational factors like audience disposition. Cicero, Quintilian and others would argue that it is important to approach constructing the narrative not as an inflexible recipe for success, but rather as a guide for helping you determine the best way to arrange the main points of your speech. Later in this chapter we will discuss some tried and true organizational patterns that may further help you develop and arrange your persuasive speech, but for now we need to finish discussing the third part of a persuasive speech: the conclusion. As you are leaving the narrative, you should signal your audience that you are moving into the conclusion with a signpost, just as you would for an informative speech. 228 Crafting a Persuasive Speech Table 13.1 Emotional Appeals Goal Emotional Appeal Example5 “As a ten-year cancer survivor I am proof of the benefits of this treatment.” “When we took this approach in a similar situation my plan worked, while my opponent’s failed.” Invoke authority Point out the effects of success or failure “Just look at what happened three years ago when we faced a similar challenge, and we did nothing. It is time to act decisively.” Demonstrate state of affairs violates community values “The current crisis in our area goes against everything most of us believe in, against what our parents taught us, and ideals with which we grew up.” Ask audience to identify with those injured or insulted “My friends, think how you and your family would feel if you were treated in such a shabby manner. Put yourself in their place and ask yourself how you would feel.” un ta in he a d Pr es s Show what happens if state of affairs remains unchanged ig ht Fo Both Cicero and Aristotle noted the importance of conclusions in persuasive speeches. They knew that just as exordiums, or introductions, were the first opportunity to make a strong case to the audience, perorations, or conclusions, were the last best chance to win the audience over. In the next part of the chapter we will explain some ways in which the classical approach to crafting a persuasive speech can be incorporated by you when developing your persuasive presentations. yr Contemporary Speech Introductions and Conclusions C op Now that we have illustrated the importance of persuasive speeches to the Greeks and Romans and discussed how they understood the practice of persuasive speaking, we need to show you how these ideas translate to you and your efforts at creating persuasive appeals. In this section we will provide you with some strategies for developing effective introductions and conclusions (or, as the Greeks and Romans called them, exordiums and perorations). We will then spend the final portion of the chapter exploring several different organizational strategies for the body of a persuasive speech. Strategies for Persuasive Introductions The Greeks and Romans noted the uniqueness of introductions in providing several different options for developing them, and these observations also illustrate the differences that exist between persuasive and informative introductions. That said, there are similarities between the two types of speech 229 13 The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking ig ht Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s introductions. This section will note the similarities while also providing you with ways to effectively construct an introduction appropriate for a persuasive speech. Cicero and Quintilian’s suggestion that the introduction be the last part of the speech you write is true with persuasive as well as informative speeches. You should not set up the introduction until you know what you are going to say, as well as have an idea for the knowledge level and disposition of your audience. This information is key to making sure you effectively capture the audience’s interest, establish credibility and focus the audience’s attention. Those four goals of an introduction, you may well remember, are the same for informative as well as persuasive speeches. You need to get an audience’s attention, but as Cicero and Quintilian noted with regard to persuasive speeches, be sure to do so without offending the audience. You must be attuned to the audience’s feelings about the topic or the occasion and determine whether a traditional introduction or Ciceronian insinuation would benefit the speech most. You also need to establish your credibility almost immediately by stating why an audience should listen to you on a particular subject. Finally, you need to preview your speech’s main points in much the same way you would do so for an informative speech. One thing you should note from Cicero and Quintilian is their belief that introductions are serious. Many people believe that today the best way to get an audience’s attention is with a joke, but that is not something the Romans, or we, would recommend—especially for persuasive speeches. Telling a joke is very risky, because if people do not laugh you start off on a poor note, and you might also unintentionally offend someone in the audience, thus damaging your ability to move the audience to action. Instead of a joke, make use of the attentiongetters we discussed in Chapter Ten. Finally, students delivering a persuasive speech should be aware of what their instructors expect in an introduction. Some instructors may, for instance, also require students to state their name or the title of their speech. Be sure you know what is expected before you write your introduction. yr Table 13.2 C op Tips for an Effective Persuasive Introduction • Develop the introduction last • Capture the attention of the audience • Establish your credibility • Focus the audiences’ attention Strategies for Persuasive Conclusions Just as with introductions, there are elements common to both informative and persuasive conclusions. After reading how the Greeks and Romans approached perorations we now realize there are differences between informative and persuasive speech conclusions. In this section of the chapter we will discuss 230 Crafting a Persuasive Speech C op yr ig ht Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s the similarities and differences while also providing tips on how you can create a strong conclusion to your persuasive speech. One of the aspects of conclusions shared by both informative and persuasive speeches is the need for a signpost at the start of the conclusion. Signposts serve the same function for persuasive speech conclusions that they do for informative speech conclusions: they let the audience know the speech is almost over. Similarly, both informative and persuasive speech conclusions should summarize each of the main points in the speech and demonstrate how they connect to and support your argument. You should never introduce new evidence in a conclusion when doing this, but rather re-emphasize the fundamental points of your speech. This allows the audience to walk away from your presentation understanding your central point and how you got there. Rarely will an audience recall specific evidence you lay out, but they will remember main points. With regard to persuasive speeches this summary also enables you to build up your clincher, which can be a much more powerful statement than in an informative speech. Although both informative and persuasive speeches have clinchers, persuasive speeches allow for much more creativity and direct calls to action with their clinchers. The reason for this is simple: the general purpose of a persuasive speech is to persuade, so the last thing the audience should hear should be a call to action. The success of your persuasive speech conclusion often depends on your ability to channel and incite the proper ethos through this clincher. This is where Aristotle and Cicero’s goal of creating audience sympathy toward the speaker or topic should be accomplished. The clincher should not take long to state, and there are a variety of ways to construct an effective clincher for a persuasive speech, as we discussed in Chapter Ten. Most importantly, however, with clinchers in persuasive speeches it is essential for you to find a way to issue a call to action that the audience can reasonably and realistically accomplish. A common error novice speakers make in their persuasive speech conclusions is reserving their persuasive effort for the clincher. Do not wait until the last statement to persuade the audience. It should be the last push and should be a logical next step based on the case you laid out throughout the speech. In short, the conclusion should feed off of the body and accentuate your case and its significance for the audience. One final note about conclusions bears mentioning. Conclusions should not be very long. In fact, they should take about as long as your introduction, and thus typically account for no more than 20% of the speech time. If your conclusion rambles on it loses its effectiveness and you lose your audience. If it is too short, your audience may never truly understand the point of your speech. Remember, your conclusion is the last chance you have to underscore your case and its importance for your audience. 231 13 The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking Table 13.3 Tips for a Persuasive Speech Conclusion • Have a signpost at the beginning of the conclusion • Summarize the main points • Do not present new evidence • Emphasize fundamental points • Build up the clincher • Accentuate the speech body and case Pr es s • Do not wait this late to present persuasive appeals • Make it approximately the same length as the introduction Fo un ta in he a d . Conclusions are essential elements of any good persuasive speech. They involve letting the audience know you are almost finished, restating your argument and main points, and clinching your appeal with a call to action. They share some similarities with conclusions for informative speeches, but there are key differences you must be aware of when putting together your speech. Developing strong introductions and conclusions is only two-thirds of the process of crafting a successful persuasive appeal. In the next section we will explore the various methods that you might use to properly organize the “meat” of the speech in developing your persuasive speech. Organizational Patterns for Persuasive Speeches C op yr ig ht The general and specific purpose of a persuasive speech differ from those of an informative address, but they too help you determine how to arrange your points. A closing argument in a courtroom is a persuasive speech where the general purpose is “to persuade” and the specific purpose is tied to the facts of the case. For example, the lawyer for Kelly, who was accused of stealing money from a CVS pharmacy, gave a closing argument where the specific purpose was “to persuade the jury that Kelly did not steal the money because she had no motive or opportunity to commit the crime.” This specific purpose statement encouraged the lawyer to use a particular organizational pattern to accomplish their speaking goals. In this section of the chapter we will detail some of the common organizational strategies you can effectively employ for both persuasive speeches. Persuasive speeches have very different general and specific purposes than informative/technical speeches, but just like informative/technical speeches the specific purpose often dictates what organizational pattern should be used. Persuasive speeches can be directed at A lawyer persuading the jury 232 Crafting a Persuasive Speech 13 Spotlighting Theorists: Alan H. Monroe Pr es s Alan H. Monroe served as a member of the faculty at Purdue University in Indiana beginning in 1924. He was initially hired as an instructor in English to teach basic courses in the English Department. He quickly infused the English curriculum with classes such as Principles of Speech and Debating in English. Today, we recognize these topics as communication rather than English courses. Through Monroe’s efforts Purdue University established a strong communication department known for teaching and research.7 in he a d In 1927 Monroe became the head of the speech faculty in the English department at Purdue, but he was not formally recognized in that role until 1941. Along with other members of the then English Department at Purdue, Monroe led efforts during the 1930s to expand the curriculum, specifically adding courses in oral interpretation, public address and debate. In 1935 Monroe published the first edition of his book Principles and Types of Speech, which is now in its 16th edition, a testament to the ingenuity and importance of what Monroe accomplished while at Purdue. ht Fo un ta In 1948 Purdue inaugurated its own Ph.D. program in speech communication, largely through Monroe’s efforts. Monroe worked using relationships he had developed in the Purdue Department of Psychology to help push the Speech Communication Department toward a Ph.D. program. He eventually resigned as head of the department in 1963 having successfully entrenched communication as its own department separate from English, with a robust undergraduate and graduate curriculum. C op yr ig As a researcher Monroe is best remembered for the development of the Monroe’s Motivated Sequence model for persuasive speeches that seek immediate action. This model is still taught today, and if you look closely you can see it at play in things as varied as commercials and political speeches. Alan Monroe truly made a mark on the campus of Purdue University as well as the discipline of communication and public speaking education. a specific problem or the problem’s fundamental cause. They also can be focused on stating one option is better than another. Finally, there are persuasive speeches that attempt to move people to immediate action. Depending on which of these is your goal, you may choose any one of four potential organizational patterns. If you seek to convince an audience that a specific policy or action will solve an existing problem, the problem-solution order might be best. In this arrangement you first must convince the audience that there is a problem, and then make the case that the solution you propose will alleviate that problem. Lionel, for example, is tired of the potholes in the road in front of his house, so he attends the City Council meeting and addresses the members. First he explains 233 problemsolution order a means of organizing a persuasive speech where you discuss the problem first and follow with a discussion of your preferred solution The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking that the road in front of his house contains ten potholes in a three block span, and then informs the council that they have caused several thousand dollars in damage to the cars that drive that road in the last month alone. He then proposes to them that they use city funds to fill the potholes with macadam to avoid further damage. Here Lionel detailed the problem and proposed a solution once the problem became clear to everyone. Using the problem-solution order this speech would roughly look like the following: Body Main point: State of the Road in front of the house (Problem) Main point: Funding road repairs Pr es s I. II. Fo ht III. Main point: The state of the road in front of his house (Problem) Main point: The poor weathering of the road when last repaired (Cause) Main point: Funding for proper road repairs (Solution) ig His arrangement now is problem-cause-solution order where he first discusses the immediate problem, then explains what caused it, and finally provides a solution that addresses both the potholes and the poor street design. Continuing with the example of Lionel and the dangerous potholes, perhaps he is not the only one who has brought this issue to the attention of the City Council. In fact, the council already knows about and agrees there is a problem and its cause is poor street design. Let’s say that the day before Lionel arrives to give his speech they come out in favor of a plan to fill the potholes, but not redesign the street because it would be cost prohibitive to do so. Lionel, aware of this alternate plan, needs a different specific purpose and organizational pattern than in either of the two previous scenarios. Now his specific purpose is “to persuade his audience that by paying the money to fix the street now is a better solution than simply fixing the potholes.” He then structures the body of this speech by using comparative advantage where every main point in the argument explains why redesigning the street is better than just fixing the potholes and not addressing their root cause. C op a means of organizing a persuasive speech where you discuss the problem first, then its root cause and follow with a discussion of your preferred solution that addresses both the problem and its inherent cause Body I. II. yr problem-causesolution order un ta in he a d This can be an effective way of convincing an audience to support your plan; however it is not always the most compelling way to propose a solution. In the case of Lionel, would it not make even better sense not to just fix the problem at hand, but address its root cause as well? This would involve changing the specific purpose and, as a result, the organization of the main points in the speech. His specific purpose would change to reflect his new goal, and it would be something like this: “to persuade the audience to redesign the street where potholes have damaged cars so that they will not occur again.” The goal for Lionel now is to address the problem (potholes) by providing a solution to it and its cause (poor design of the street). comparative advantage an organizational pattern that uses each main point to explain why the speaker’’s solution is better than another proposed solution. 234 Crafting a Persuasive Speech Body I. II. III. 13 Main point: Fixing potholes is temporary, proper repair permanent Main point: Fixing road creates smoother surface Main point: Fixing road correctly less expensive in long run Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s The case of Lionel and his topic illustrates ways of organizing persuasive speeches regarding policy in situations where immediate action is neither sought nor required. What about those speeches where immediate action is the goal? The fourth organizational pattern for your main points we will discuss provides a way to effectively arrange a speech designed to incite immediate action in your audience. Alan Monroe, a professor at Purdue University, developed what we call Monroe’s Motivated Sequence in the 1930s. The five-step sequence combines psychological elements with speech persuasion in an effort to move an audience to action. First, Monroe advocated something the Greeks and Romans we discussed earlier also called for: getting the attention of your audience. Then he argued a speaker should clearly lay out the need for change, something again advocated by the classical philosophers we discussed earlier. Once you clearly establish the problem you satisfy the need by providing a solution to that problem. Fourth, Monroe’s sequence calls for you to intensify the audience’s desire for your solution to the problem by visualizing its success. This involves the use of imagery, and asks the audience to actually see themselves doing what you call for—at least to see it in their mind’s eye. Finally, once you state your case and have gotten your audience to visualize what life would be when it was successful, using emotionally stirring language you tell them how to act.6 As an example: a student wants to persuade his audience to get involved in cleaning up a nearby park that is strewn with trash and debris. He then composes the following order for his points using Monroe’s Motivated Sequence: “Do you think we should have a pleasant outdoor place to enjoy nature, to hang out with friends?” To take walks, play sports, have cookouts and entertain? Need: “We do not have that on our campus, and there is a nearby park we could use, but it is overrun with weeds, trash, and is currently unacceptable.” (Pictures would be a good visual aid at this juncture) Satisfaction: “We could all pitch in, share the work, and it would not be that big a burden on anyone.” Visualization: “A place to hang out, play ball, walk, enjoy fresh air and nature, and have cookouts, and we would have made that possible.” (Visuals of a beautiful outdoor setting would be effective at this point). “Will you join me in making this dream come true? Again, Action: the work will be shared, and we will have made an improvement for all to enjoy.” C op yr ig ht Attention: Obviously, this scenario would need to be fleshed out in detail, but, again, the motivated sequence can be a highly effective model for the speaker to use. 235 Monroe’s Motivated Sequence a five-step organizational pattern that combines psychological elements with speech persuasion to move an audience to action The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking Whether you are debating policy positions, factual accuracies, the value of one solution over another, or calling an audience to act there are a wide variety of organizational patterns you can use in a persuasive speech. Just like informative speeches, persuasive speech arrangement largely depends on the formulation of your specific purpose, but once that is crafted the speech can quickly take shape. Knowing what the main parts of a speech are, and how you can organize your main points help you get ready to prepare your presentation. The most crucial step in speech creation remains organizing the product of your research in a cogent, coherent and persuasive manner. Table 13.4 • Problem-solution • Problem-cause-solution • Comparative advantage Summary un ta S in he a • Monroe’s Motivated Sequence d Pr es s Organizational Patterns for Persuasive Speeches C op yr ig ht Fo The Greeks and Romans separated persuasive speeches into a variety of different parts: the exordium, narrative and peroration. They paid particular attention to the narrative and broke it down into several component parts including the statement of facts, argument proper, and refutation. Today we use terms like introduction, body and conclusion to describe the elements of a speech, but the ideas about what must be done in each part to achieve a persuasive purpose are the same. In this chapter we also identified some of the common elements between informative and persuasive speeches, while also elaborating on the differences; most notably those differences related to the various different ways you can organize a persuasive speech. Finally, we encourage you to look at the appendix on outlining at the end of the textbook so you can see models and a worksheet for helping you develop your persuasive speech. K Key Terms argument - 227 comparative advantage - 234 exordium - 224 insinuation - 225 introduction - 225 Monroe’s Motivated Sequence - 235 236 peroration -228 principle of recency - 228 problem-cause-solution order - 234 problem-solution order - 233 refutation - 227 statement of fact - 226 Crafting a Persuasive Speech R Review Questions 1) What are the three components of persuasive speeches according to the Greeks and Romans? 2) What are the two types of exordiums proposed by Cicero? 3) What four things did Aristotle say a peroration should do? 4) What are the four ways you can organize the main points in a persuasive speech? Think About It 1) Would it ever be a good time to present your strongest argument first? 2) How do you measure whether your credibility increases or decreases d during a speech? in he a 3) Is it ethical to induce emotions in a conclusion, or any part of the speech? yr ig ht Fo un ta Why or why not? C op T Pr es s 5) What are the five parts of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence? 237 13 The Speaker: The Tradition and Practice of Public Speaking Endnotes C op yr ig ht Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s 1 Toastmasters International, “What is Toastmasters?” http://www.toastmasters.org/ MainMenuCategories/WhatisToastmasters.aspx (accessed: September 19, 2008). 2 Toastmasters International, “Community Service,” http://www.toastmasters.org/ MainMenuCategories/WhatisToastmasters/CommunityService.aspx (accessed: September 19, 2008). 3 Quintilian, The Institutes of Oratory, translated by H.E. Butler, Loeb Classical Library. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980, IV, i 5). 4 Ibid, V, xii, 5. 5 Sharon Crowley and Debra Hawhee, Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students, 4th Ed. (New York: Pearson Education, 2008). 6 Raymie E. McKerrow, Bruce E. Gronbeck, Douglas Ehninger, and Alan H. Monroe, Principles and Types of Speech Communication, 15th Ed. (New York: Longman: 2003). 7 W. Charles Redding, “An Informal History of Communication at Purdue,” http:// www.cla.purdue.edu/communication/graduate/informalhistory.pdf. 238 C op yr ig ht Fo un ta in he a d Pr es s Crafting a Persuasive Speech 239 13

© Copyright 2026