The Influence of Financial Poverty on Academic Success

Handout Materials

The Influence of

Financial Poverty on

Academic Success

Robert Bligh

Omaha, NE

March 17, 2015

Third Annual

Critical Issues Forum

Education Administration Department

University of Nebraska - Lincoln

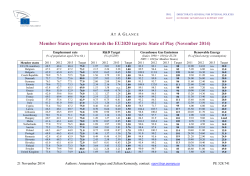

2011-12

Fifteen Largest Nebraska School Districts

2012 FRL Poverty and 2012 NeSA Reading, Math and Science Proficiency

NDE Data

After more than a decade of NCLB "reforms."

District

Building

Grade Poverty Reading Math Science

Omaha - 50,330 students - 71% poverty

Lincoln - 36,523 students - 44% poverty

Millard - 32,075 students - 18% poverty

Elkhorn

Elkhorn

Millard

Ridge

View

Russell

Middle

Middle

Middle

2.7

2.9

7.9

138

130

135

130

126

123

123

126

128

Papillion - 10,335 students - 23% poverty

Bellevue - 9,988 students - 32% poverty

Millard

Lincoln

Beadle

Lux

Middle

Middle

8.5

10.7

131

140

117

127

115

117

Grand Island - 9,035 students - 64% poverty

Elkhorn - 6,059 students - 7% poverty

Westside - 5,963 students - 29% poverty

Millard

Lincoln

Elkhorn

Kiewit

Scott

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

11.4

13.0

15.3

131

131

130

118

124

124

123

110

118

Kearney - 5,287 students - 40% poverty

Fremont - 4,524 students - 53% poverty

No. Platte - 4,186 students - 42% poverty

Papillion

Bellevue

Millard

Papillion

Lewis & Clark

North

Middle

Middle

Middle

18.0

19.3

21.0

122

125

132

105

108

121

111

111

117

Norfolk - 4,015 Students - 48% poverty

So. Sioux City - 3,743 students - 68% poverty

Columbus - 3,733 students - 50% poverty

Hastings - 3,634 students - 57% poverty

Fifteen districts - 63% of Nebraska students

Lincoln

Millard

Omaha

Papillion

Westside

North Platte

Grand Island

Millard

Bellevue

Kearney

Bellevue

Lincoln

Lincoln

Lincoln

Pound

Andersen

Buffett

La Vista

Westside

Adams

Westridge

Central

Fontenelle

Horizon

Mission

Schoo

Mickle

Irving

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

25.9

26.1

26.2

27.7

30.3

34.4

35.6

35.7

39.2

40.5

41.9

42.6

42.7

43.2

129

119

128

120

120

111

123

120

121

121

114

111

116

124

122

102

104

104

124

102

123

105

108

100

93

101

111

115

114

109

101

107

123

105

112

107

102

93

102

91

96

109

District

Elkhorn

Millard

Elkhorn

Millard

Lincoln

Papillion

Lincoln

Building

South

West

North

North

East

South

Southwest

Bellevue

Papillion

Westside

Millard

Lincoln

Bellevue

North Platte

Kearney

Columbus

Norfolk

Fremont

West

North

Westside

South

Southeast

East

North Platte

Kearney

Columbus

Norfolk

Fremont

High

High

High

High

High

High

High

High

High

High

High

20.7

23.2

25.6

27.1

29.2

30.7

32.4

36.1

39.9

41.2

43.1

116

114

105

101

103

108

100

95

101

103

103

105

110

110

87

101

91

90

88

96

97

85

107

102

106

100

100

96

96

101

103

99

95

Kearney

Norfolk

Columbus

Lincoln

Fremont

Hastings

Omaha

Omaha

North Platte

Grand Island

Lincoln

Sunrise

Norfolk

Columbus

Lefler

Fremont

Hastings

Morton

Beveridge

Madison

Barr

Park

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

49.1

50.8

51.0

53.6

54.9

57.8

60.7

65.4

66.3

66.6

70.5

109

107

103

120

109

111

99

94

91

107

109

104

103

105

111

97

111

80

77

82

104

96

104

91

92

104

103

95

85

80

87

98

86

Omaha

Hastings

Burke

Hastings

High

High

45.1

49.9

91

98

82

92

91

95

Omaha

Lincoln

Lewis & Clark

Dawes

Middle

Middle

71.0

71.2

90

101

72

93

74

91

High

High

High

High

50.2

51.3

57.4

57.4

95

92

86

89

85

92

89

85

96

92

92

90

So Sioux City So Sioux City

Omaha

McMillan

Omaha

King

Lincoln

Goodrich

Middle

Middle

Middle

Middle

72.1

72.2

74.7

76.4

96

96

92

98

81

80

78

95

89

74

80

95

Lincoln

Northeast

Lincoln

North Star

Grand Island Grand Island

So Sioux City So Sioux City

Grade Poverty Reading Math Science

High

3.5

129

129

114

High

8.8

114

105

110

High

11.8

125

126

115

High

13.1

123

109

112

High

13.3

125

122

113

High

16.1

125

112

109

High

18.0

106

97

92

Omaha

Lincoln

Central

Lincoln

High

High

58.5

61.0

97

86

86

85

92

88

Grand Island

Omaha

Walnut

Hale

Middle

Middle

77.7

79.5

95

74

95

58

80

60

Omaha

Omaha

North

Northwest

High

High

63.6

73.6

82

77

73

60

86

80

Lincoln

Omaha

Culler

Bryan

Middle

Middle

79.9

81.1

104

78

98

68

92

73

Omaha

Omaha

Omaha

Benson

Bryan

South

High

High

High

77.4

78.1

84.8

65

71

69

57

59

58

71

77

69

Omaha

Omaha

Omaha

Marrs

Monroe

Norris

Middle

Middle

Middle

84.7

86.9

89.2

100

78

82

96

63

69

79

68

69

-0.95

-0.92

-0.93

-0.92

-0.83

-0.90

Correlation of Student Poverty to NeSA Scores

Rob Bligh - Nov. 20, 2012

Correlation of Student Poverty to NeSA Scores

Handout Page 2

http://reportcard.education.ne.gov/

Handout Page 3

!"#$%&#'(#)!'*#%+,-&.'

/%01'%-+')2,#-2#')23$#4'

53$'6788986'

!"#

$"#

%"#

&""#

&'"#

&!"#

"#

&"#

'"#

!"#

)"#

$"#

:#$2#-0'35';*<')0=+#-0':3"#$0>'

("#

GH-2A=+#4'I?'J#$2#-0'35'(#B$%4C%')0=+#-04K'''

*"#

%"#

?8'@,&1')2133A4',-'(#B$%4C%D4'8E'<%$('F,40$,204'

+"#

Academic “Matthew Effects” of a Childhood in Poverty

For a large majority of children who spend their childhoods immersed in poverty, the experience has

many cognitive, behavioral, and motivational consequences that impede the development of their

academic skills and inhibit their performance on many academic tasks. As a child faces the many

challenges of academic development, the attitudes, habits and expectations that accompany poverty

interfere persistently with the child’s efforts.

Impediments to the acquisition of academic skills and knowledge that are generated by a childhood in

poverty confront such children at every academic turn. Every early failure to develop academically

impedes the child’s later academic development. The longer this sequence is allowed to continue, the

more generalized the deficits become, seeping into more and more areas of cognition and behavior.

With the exception of certain* conditions and events, I do not suggest that a child born into poverty

is in any meaningful sense instantly immune to education. What I do contend is that living in poverty

tends to “teach” a child attitudes, expectations and behaviors that, once adopted, are inconsistent

with successful academic achievement and successful adult life. The result is a wildly disproportionate

fraction of such children who seem to be either education-resistant or education-proof, despite 48

years of honest efforts by K-12 teachers.

Consider the likely truth (and the likely educational impact, if true), of each of these 20 propositions:

1.

A typical American child spends less than 9 percent of childhood in a K-12 school even if that child

has perfect attendance for all 13 school years.

2. Children living in poverty tend to be absent oftener than more affluent children; thus, their ratio

of school time to non-school time is even smaller than that of more affluent children.

* More premature births, lower birth weights, and greater exposure to chemical pollutants generate additional

poverty-related impediments to the academic development of children forced to live immersed in poverty.

December 7, 2013

Handout Page 4

Rob Bligh

Academic “Matthew Effects” of a Childhood in Poverty

3. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are less likely to express and demonstrate positive

expectations for children than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

4. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are less likely to express and demonstrate respect for

children, their intelligence and their curiosities than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

5. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are more likely to express and demonstrate a belief

in institutionalized victimhood more than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

6. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are more likely to see children’s needs in

competition with their own needs than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

7. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are less likely to express and demonstrate respect

for self-discipline than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

8. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are less likely to express and demonstrate respect

for education than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

9. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are less likely to include examples of academic

success than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

10. Adults in the lives of children living in poverty are likely to have a greater need for - and less

access to - mental health services than adults in the lives of more affluent children.

11. Fathers of children living in poverty are likely to have less contact - and less positive contact with their children than fathers of more affluent children.

12. Children living in poverty are less likely to have access to age appropriate books and magazines

than more affluent children.

13. Children living in poverty are more likely to experience food insecurity and meaningful threats of

food insecurity than more affluent children.

14. Children living in poverty are likely to experience more alcohol and drug abuse among adults than

more affluent children.

15. Children living in poverty are likely to experience more violence and more meaningful threats of

violence than more affluent children.

16. Children living in poverty are likely to enter kindergarten with vocabularies less (and in many cases

far less) than half the size of the vocabularies of more affluent children.

17. Children living in poverty are more likely to move from place to place - and from school to school at a rate greater than more affluent children.

18. Children living in poverty are less likely to travel than more affluent children.

19. Children living in poverty are less likely to have regular meaningful conversations with adults than

more affluent children.

20. Children living in poverty are less likely to have responsible adult supervision outside school than

more affluent children.

December 7, 2013

Handout Page 5

Rob Bligh

Brown and UNK

Student Quality and Academic Success

Brown University’s undergraduate

students are of unusually uniform high

average quality. Evidence for this is the

published median ACT score for Brown

first year students of 32.

The academic quality of University of

Nebraska

at

Kearney’s

(UNK)

undergraduate students is very much

lower. Evidence for this is the published

median ACT score for UNK first year

students of 23.

It would be remarkable if more than a

very small fraction of UNK’s first year

students would even qualify for

admission to Brown.

The academic success of Brown’s

undergraduate students is uniformly

high. Evidence for this is the published 4year graduation rate of 86 percent.

The academic success of UNK’s

undergraduate students is very much

lower than those at Brown.

Evidence for this is the published 4year graduation rate of 22 percent.

Indeed, the published 6-year graduation

rate at UNK is only 58 percent.

There is, of course, some small number

of relatively high quality undergraduate

students who enroll at UNK.

Such students tend strongly to earn

good grades, graduate on time, gain

acceptance to high quality graduate and

professional schools, and otherwise

succeed academically by any measure

that could be applied to Brown students.

Such a result is not surprising for such

students, but it simply is not the result for

the overwhelming majority UNK students

whose average academic quality is very

much lower than those at Brown.

Indeed, every such high quality

exception at UNK drives the average

quality of the remainder further down.

Consider this thought experiment.

Imagine the result if Brown were to enroll

only undergraduate students of the

average academic quality of the students

who now regularly enroll at UNK.

It seems reasonable to suspect that the

academic success of such students would

be little – if any – better than the regular

result at UNK, irrespective of the relative

pedagogical skills of the two faculties.

Similarly, imagine that UNK enrolled

only undergraduate students of the

average academic quality of the students

who now regularly enroll at Brown.

It would be reasonable to suspect that

the academic success of such students

would be little – if any – worse than the

regular result at Brown, irrespective of the

relative pedagogical skills of the two

faculties.

I do not mean to denigrate either the

pedagogical skills or the academic

expertise of the faculty members at either

institution.

I merely mean to suggest that the

relative academic success of the

undergraduate

students

at

each

institution can be substantially explained

in terms of the relative academic quality

of the students at initial enrollment.

The quality of a finished product is

limited by the quality of the raw material

no matter how skilled the craftsman.

The following short locker room

speech was delivered by a very successful

college track coach after his team had

failed to do as well as expected at the

NAIA national indoor championships in

Kansas City.

“I know that this loss today is a bitter

disappointment for everyone in this

room. I want to assure you all that today’s

result was all my fault. I take full

responsibility. I should have recruited

better athletes.

– Rob Bligh, Omaha, March 11, 2014

Handout Page 6

From: Christopher Fitch <[email protected]>

Date: Wednesday, April 2, 2014 at 11:09 AM

To: Rob Bligh <[email protected]>

Cc: "Deeann R. Goeser" <[email protected]>

Subject: OPS Data Request

Mr. Bligh,

Attached you will find two data files containing the data you requested regarding paired

Nebraska State Assessment (NeSA) scale scores from the 2011-12 and 2012-13 school years.

The first file contains NeSA math scale scores and the second file contains NeSA reading scale

scores. Both files include each student's school and grade level for both 2011-12 and 2012-13.

Based on our previous discussions, I have also included a table below illustrating the correlation

between 2011-12 and 2012-13 NeSA scale scores. This table contains the overall correlation for

all students, as well as correlations by grade level based on the students' 2012-13 grade. As you

can see, the correlations were quite high and statistically significant regardless of grade level.

Correlation between 2011-12 and 2012-13 Nebraska State Assessment

Scale Scores by Grade Level

2012-13 Grade Level

NeSA Math

NeSA Read

4

0.80*

0.78*

5

0.79*

0.78*

6

0.80*

0.81*

7

0.82*

0.79*

8

0.86*

0.84*

All Grades Combined

0.81*

0.80*

*Indicates that the correlation is statistically significant; p < 0.05.

Thank you for your continued interest in the Omaha Public Schools. As always, please feel free to

contact me at 402-557-2088 if you have any questions or wish to discuss the provided

information further. Have a wonderful day!

Sincerely,

Chris Fitch, M.S.

Evaluation Specialist

Division of Research

Omaha Public Schools

Voice: (402) 557-2088

Fax: (402) 557-2049

Handout Page 7

Breaking News

June 24, 2014

www.aapnews.org

Parents who read to their children nurture more than literary skills

by Lori O’Keefe • Correspondent

Reading proficiency by third grade is the most significant predictor

of high school graduation and career success, yet two-thirds of U.S.

third-graders lack competent reading skills. A new AAP policy statement recommends that pediatric providers advise parents of young

children that reading aloud and talking about pictures and words in

age-appropriate books can strengthen language skills, literacy development and parent-child relationships.

Literacy promotion during preventive visits has some of the

strongest evidence-based support that it can make a difference in the

lives of young children and families, said Pamela C. High, M.D.,

M.S., FAAP, lead author of Literacy Promotion: An Essential Component

of Primary Care Pediatric Practice, http://pediatrics.aappublications.

org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-1384. The policy, released June 24,

will be published in the August Pediatrics.

Promoting early literacy development in the pediatric primary

care setting was a resolution at the 2008 AAP Annual Leadership

Forum, leading to development of the policy statement. Dr. High

is past chair of what now is the AAP Council on Early Childhood,

which authored the policy.

Multiple benefits

Children who are read to during infancy and preschool years have

better language skills when they start school and are more interested

in reading, according to research highlighted in the statement. In

addition, parents who spend time reading to their children create

nurturing relationships, which is important for a child’s cognitive,

language and social-emotional development.

“When I started with Reach Out and Read years ago, efforts were

focused on early literacy and school readiness,” said Perri Klass, M.D.,

FAAP, national medical director of Reach Out and Read and contributing author to the policy statement. “Although those are still

tremendously important, the bigger picture now is to help parents

build interactions with their children into their everyday lives because

this can create nurturing relationships, which promote early brain

development, early literacy, language development and school readiness.”

Make it fun

An important job for pediatric providers is to help parents understand what is developmentally appropriate for their child and how

to make reading fun, Dr. Klass said. “A parent shouldn’t read a long

story to an infant or young child and expect them to listen attentively.”

Dr. Klass recommends parents point to and name pictures in books

for infants and ask young children questions or have them complete

rhymes from a short book.

Parents need to understand that 2-year-olds have a short attention

span, and infants may put books in their mouths because that is how

they explore their world, she said.

“We don’t want a parent to feel that their child is failing at reading

if the child loses interest,” Dr. Klass added.

Powerful tool for all

Books also can be a useful tool during well-child visits.

Making books part of preventive visits allows pediatric providers

to observe fine motor skills, language, literacy and parent-child interaction. Incorporating books into a visit also enables health care professionals to model book interaction with patients, according to the

policy statement.

According to the 2011-’12 National Survey of Children’s Health,

only 60% of children from families with incomes 400% above the

poverty level and 34% of children from families below 100% of the

poverty level are read to daily. Every family, regardless of income,

should be counseled about the importance of reading together, said

Dr. High.

The policy statement recommends providing books to patients

who are at financial and social risk and exploring options to obtain

books if they are cost-prohibitive.

The statement also recommends:

• hanging posters that promote reading;

• distributing information to parents about reading and local

libraries;

• partnering with child advocates to influence national messages

and policies about literacy;

• promoting the “5 R’s” of early education: reading, rhyming, routines, rewards and relationships;

• incorporating literacy promotion and training into pediatric resident education;

• supporting state and federal funding to distribute books to highrisk children at pediatric visits; and

• researching the effects and best practices of literacy promotion.

“Books are a useful tool,” Dr. High said, “but we also want parents

to understand that reading to their children is so powerful because

children think their parents are the most important people in their

world.”

RESOURCES

• Literacy promotion in pediatric practice, http://bit.ly/1uBySnv

• Reach Out and Read, www.reachoutandread.org; summer reading list,

http://bit.ly/ULVtmN

• New collaborate effort to promote early literacy (launched June 24),

http://bit.ly/1qurfiN

Handout Page 8

Freshman Quality and Graduation Rate

Undergraduate

Institution

Phoenix KCMO

Admission Freshman Four Year Five Year Six Year

Percent ACT Median Graduation Graduation Graduation

100.0

--1.5

13.2

13.2

NE Peru

100.0

---

9.7

31.8

36.9

NE Chadron

100.0

---

24.2

41.1

45.5

NE Wayne

100.0

---

23.2

43.3

47.5

NE Saint Mary

42.4

21

43.6

45.5

46.5

NE Midland

48.5

22

44.8

52.4

52.4

Nebraska-Omaha

80.4

23

12.7

35.4

44.8

South Dakota

87.0

23

25.0

45.6

49.6

So. Dakota State

93.5

23

25.2

49.3

54.5

NE Doane

76.2

23

53.5

55.4

55.4

NE Union

41.3

23

32.1

54.0

56.9

Nebraska-Kearney

76.5

23

22.4

49.3

57.6

Arizona State

90.3

23

32.3

53.1

59.1

NE Hastings

74.3

24

52.6

64.0

64.7

Northern Iowa

84.8

24

35.2

61.7

67.0

NE Concordia

75.1

25

37.1

57.2

59.7

NE Wesleyan

82.5

25

52.1

63.8

65.0

Iowa State

87.3

25

36.7

65.8

70.2

Nebraska-Lincoln

62.9

26

29.4

58.0

64.2

Millsaps

73.6

26

61.2

66.9

68.0

Iowa

83.0

26

44.2

66.5

69.6

NE Creighton

81.8

27

65.4

75.9

76.8

Texas A&M

66.9

27

46.2

75.7

79.9

Texas Austin

45.3

27

52.5

75.7

80.3

Trinity (TX)

59.1

29

67.7

77.2

78.4

Michigan

50.0

29

72.0

87.5

89.7

Columbia

11.0

32

84.6

90.8

92.5

Stanford

8.0

32

78.4

92.2

94.7

Brown

11.2

32

85.7

94.2

95.6

Harvard

7.2

33

87.1

95.9

97.4

0.85

0.95

0.96

Correlation of ACT and Graduation Rate:

Source: http://www.collegeresults.org/

Handout Page 9

Academic Success Among Financially Impoverished Children

The information on which this document is based was taken from data posted on the Nebraska Department

of Education websites and data provided by the Research Office of the Omaha Public Schools. It covers

the 2011-12 school year. See next page. “FRL” indicates students whose households qualify for free-orreduced meal benefits under applicable standards of the United States Department of Agriculture.

(1) OPS total K-12 enrollment was 50,014 students.

(2) Approximately 71 percent, or 35,560 OPS students qualified for FRL benefits.

(3) NeSA Reading Tests were given to all OPS students in grades 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 11.

(4) A total of 14,214 FRL students took the NeSA Reading Tests.

(5) Of those 14,214 FRL students, 8,013 (or 56 percent) scored “satisfactory” or above on the NeSA

Reading Tests.

(6) 56 percent of all OPS FRL students would equal approximately 19,914 students.

(7) If 19,914 financially impoverished but academically successful students were in a separate school

district, (a) it would be the fourth largest district in Nebraska, (b) it would be nearly twice as large

as the fifth largest district and (c) it would be the only Nebraska school district in which 100

percent of the students were financially impoverished and 100 percent of the students were

academically successful in reading.

(8) NeSA Math Tests were given to all OPS students in grades 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 11.

(9) A total of 14,328 FRL students took the NeSA Math Tests.

(10) Of those 14,328 FRL students, 6,301 (or 44 percent) scored “satisfactory” or above on the NeSA

Math Tests.

(11) 44 percent of all OPS FRL students would equal approximately 15,646 students.

(12) If 15,646 financially impoverished but academically successful students were in a separate school

district, (a) it would be the fourth largest district in Nebraska, (b) it would be over 50 percent

larger than the fifth largest district and (c) it would be the only Nebraska school district in which

100 percent of the students were financially impoverished and 100 percent of the students were

academically successful in math.

Conclusions

Impoverished students tend disproportionately to fail in school.

About half of impoverished OPS students succeed in school.

Same schools. Same classrooms. Same books. Same classmates. Same curricula. Same teachers. Same

assignments. Same tests. Same poverty.

Different families.

Rob Bligh

Omaha

June 20, 2013

Handout Page 10

K-12 Schools as

Substitutes for Inadequate Parents

Suicide Prevention Training

Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation Training

School Medical Clinics

School Mental Health Services

Free-or-Reduced Meals

Afternoon Social Services

Parental Involvement Policies

Prenatal & Neonatal Training

Student Health Data Collection

Student Weight Reduction

Handout Page 11

Analysis of Central Park Student Achievement by School Choice Groups

Using 2011-12 NeSA Results

The following report compares 2011-2012 NeSA Reading and Math scale scores from three

different groups of students. The first group is comprised of students attending Central Park

Elementary who are living in the school’s home attendance area (Students Remaining at Central

Park). The second group is comprised of students attending Central Park who are from outside the

school’s home attendance area (Students Choosing Central Park). The final group is comprised of

students from the home attendance area of Central Park who chose to attend another school

(Students Leaving Central Park). To be included in this analysis, students had to have taken the

NeSA in 2012, and they had to have attended their current school for at least two years. Students

who had attended their current school for less than two years were omitted from the sample

because it is less likely that their NeSA scores were significantly impacted by their current school

of enrollment. The mean NeSA Reading and Math scores along with standard deviations for each of

these groups are presented in Table 1. In addition, this table includes the number of students

comprising each group.

Table 1. Mean NeSA Reading and Math Scores.

Student Group

Home Attendance

Area Students

Remaining at Central

Park

Students Choosing

Central Park

Students Leaving

Central Park

NeSA Math Scale

Score

M =111.75

SD = 29.53

N = 64

M =107.38

SD = 28.14

N = 104

M =80.11

SD = 30.35

N = 75

NeSA Reading Scale

Score

M =112.81

SD = 36.44

N = 64

M =116.01

SD = 30.87

N = 104

M =88.88

SD = 34.12

N = 75

Analysis & Results

To further analyze these observed mean differences, an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was

conducted. This analysis allowed for the comparison of mean group NeSA scores while controlling

for group demographic differences including free/reduced price lunch program participation,

special education status, gifted and talented status, English as a second language status, and

minority status. In general, demographic data suggested that the three groups in this analysis were

fairly similar in makeup. However, the ANCOVA results suggested that the groups did differ in

terms of mean NeSA Math (F=26.15, p < .05) and mean NeSA reading scores (F=13.41, p < .05). The

groups’ mean NeSA Math and Reading scores adjusted for group demographic characteristics along

with the standard error of each are presented in Table 2.

Handout Page 12

Grand Island - Wasmer Elementary School – Student Transfers

Student Group One

Student who lived within the Home Attendance Area of Wasmer who attended

Wasmer

Math: Number 111 - Average scaled score 134.98

Reading: Number 111 - Average scaled score 121.36

Student Group Two

Student who lived within the Home Attendance Area of Wasmer who attended a

GIPS elementary school other than Wasmer

Math: Number 35 - Average scaled score 100.14

Reading: Number 34 - Average scaled score 99.78

Group Three

Students who lived outside the Home Attendance Area of Wasmer who attended

Wasmer

Math: Number 45 - Average scaled score 131.58

Reading: Number 45 - Average scaled score 117.98

At Wasmer, (1) the ablest students stay, (2) the least able students leave and (3)

those who transfer in are roughly as able as those who stay and much abler than

those who leave.

There might be other reasons for Wasmer’s and CPE’s stark and utterly

unexpected academic success. There might even be pedagogical reasons of the

success. Nevertheless, it is very rational to suspect that the Wasmer/CPE success

is caused by the fact the students who enroll at each school are

disproportionately among the ablest impoverished students in each district. Those

who leave are among the least able.

In Omaha, about half of the 35,000 impoverished students score at-or-aboveproficient on the state’s tests.

If you can somehow place a couple hundred of the children from the successful

half into one school, you can make that school look like a miracle school.

Handout Page 13

Local View: Better Childhoods Needed

Rob Bligh – Omaha – July 3, 2012

We should stop thinking of the

disproportionate academic failure of poor

children as a sign of the failure of our schools.

Instead, we should begin to recognize it as

the modern-day equivalent of canaries in a

coal mine.

Before the development of sophisticated

devices to detect and warn of the presence of

odorless, tasteless and colorless — but very

deadly — methane gas that could seep into a

working coal mine, miners would take caged

canaries with them to work.

When the canaries — with practically no

tolerance for methane — began to collapse,

the miners knew that methane was in the air

they were breathing and that it was time to

vacate the mine or begin to lose

consciousness and quickly die.

If more children are failing in our schools,

it is largely because more are spending

childhood immersed in poverty.

Poor children are failing at the same rate

as they always have. We are noticing it more

lately because poor children are becoming a

larger and larger proportion of America’s

birth-to-18 population.

Their noticeable failure should be

interpreted just as the miners used to

interpret unconscious canaries. America is

generating the cultural equivalent of deadly

methane to the extent that it allows its future

citizens to reach the age of adulthood without

being effectively nurtured as children.

I am beginning to think that there is only

one thing on which America should be

spending resources to promote the academic

advancement of children living in poverty.

We should do whatever we can to make

the 50,000 hours between conception and the

first day of kindergarten more stable, more

humane, more friendly, more supportive, less

toxic, healthier, more attentive, more

nutritious, safer, less threatening, less

abusive, more nurturing, more respectful, less

neglectful, etc.

The futile “reform” of our K-12 schools

certainly is not the answer. School reform has

failed consistently since it first became

politically popular in 1965. Schools don’t fail.

Some students fail in school. Most of the

students who fail are students who spend

childhood immersed in poverty. Less than 9

percent of any childhood is spent in school.

The other 91 percent is spent someplace else.

To the extent that America can make the

conception-to-kindergarten lives of its poor

children more like the lives of its non-poor

children, a growing share of our children will

succeed in school and a growing share of our

children will become contributing adults.

Every year, in every school in America, a

significant minority of poor children do every

bit as well in school as their non-poor

classmates.

This very probably is because their

parents — even in the face of numbing

poverty — go to very considerable trouble to

actively nurture and guide their children.

Every child deserves that kind of childhood.

Most non-poor children get it. Most poor

children do not.

There is plenty of reason for despair about

the prospect for America’s children. When I

was in school (45 years ago), poverty wore a

metaphorical hearing aid.

Today, thanks to Social Security COLAs

and limitless Medicare benefits, poverty in

America has exchanged the hearing aid for a

diaper. Americans over 65 constitute our

wealthiest cohort by age.

Conversely, nearly one in every four

American children now lives in poverty, and

that fraction is growing.

I and other members of my “baby

boomer” cohort are signing up for Social

Security and Medicare and George W. Bush’s

prescription-drugs-for-old-timers program at

a rate of 10,000 every 24 hours.

That's another adult at the public trough

every 8.7 seconds around the clock, every day

of the year. That rate is scheduled to continue

unabated through 2038.

And we vote. And children do not.

Poor children don’t need better schools.

Poor children need better childhoods. The

future of America depends upon it. If

America cannot respond to this need,

America will not succeed.

Nor will it deserve to.

Handout Page 14

Things Educators Could Say But Don’t

Valerie Strauss – The Answer Sheet – October 8, 2012

With reform policies based more on hope than data, you might think educators would speak up more than do.

Why don’t they? Here are some thoughts about why most stay quiet, from Robert Bligh, former general counsel

of the Nebraska Association of School Boards. Bligh’s research interest involves the efficacy of the school reform

efforts promoted by the Elementary and Secondary Education Act since its original adoption in 1965. He served

as assistant professor at Doane College and was editor and publisher of the Nebraska School Law Reporter.

Robert Bligh

Many public policies – especially those

established at the federal level – seem to be riddled

with “reasons” that are based more on hope than

data. No category of public policies fits this

description better than America’s public policies on

K-12 education.

About 37 years ago, when I became the first

agency legal counsel at the Nebraska Department of

Education, I began to suspect that K-12 teachers and

their schools were being held responsible for things

that were completely beyond their reach. Most of

what I have observed since about K-12 education

has supported that suspicion.

Federal statutes governing public education

have been based more on hope than data since at

least 1965. That was the year the Elementary and

Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was adopted as

part of President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society.”

ESEA’s fundamental approach was to order

teachers and schools to solve a host of noneducation social problems that all other social

institutions – especially families and churches – had

failed to solve. ESEA — better known in its current

form as No Child Left Behind — and its legislative

progeny have all failed. All of the problems have

gotten worse rather than better.

I have long been surprised that these irrational

policies have been adopted and readopted without

serious objection by most education practitioners.

Educators could say all of the following:

1. To Parents: “If you effectively raise your children

before you send them to school, we can teach

most of them. If you do not, we cannot.”

2. To Legislators: “Do not order us to repair the

developmental damage that is done to children

before they reach school age. We cannot do so

and pretending otherwise wastes resources,

damages K-12 education and does nothing to

help those utterly innocent children who need it

(and deserve it) most.”

3. To Reformers: “Academic achievement gaps,

robust and intractable, are well-established long

before the first day of kindergarten. Those gaps

are not caused by teachers and cannot be fixed by

teachers. What you like to call ‘reforming’ schools

does nothing to help children who spend their

first five years living in inadequate, often chaotic,

households. If you want to help those children,

you must do something to change those

households. Any other approach is foolish,

wasteful and destined to fail.”

Educators could say those things, but, with rare

exceptions, they do not. Consider the following

speculation as a possible way to explain why

educators are mostly silent when their profession is

slandered by politicians and pundits and crippled

by irrational public policies.

I suspect that those people who are attracted to

the teaching profession strongly tend to be much

more humanely motivated than the rest of us. By

that, I mean that teachers tend to believe deeply that

human behavior is significantly influenced by

human experience: the better people are treated, the

better they will behave.

For teachers, K-12 education is a formalized

process of treating children in a manner that will

tend to make them become more civilized as they

mature.

Of course these humane tendencies serve

teachers very well in dealing with their students.

Indeed, for very many children, educators are the

only humanely motivated adults in their lives.

Furthermore, I suspect that these humane

motivations are absolutely necessary in order to face

classrooms, day-after-day and year-after-year, that

almost all include from a few to a great many

children who are destined to go through school as

academic failures, no matter what any teacher does.

For example, consider our depressingly reliable

ability to identify – before they enter the 4th grade –

those children who will drop out before graduation.

I suspect that a person who is not deluded into

believing that every child can be educated could not

tolerate being a teacher for very long.

I do not use the term “deluded” to belittle

educators. I am convinced that the only people I

want to be in charge of a K-12 classroom are those

who believe that all children can be educated —

irrespective of all data to the contrary.

However, what might be a necessity in a teacher

is a tragedy in a public policy maker. We have

accumulated 47 years of data to support that

conclusion. School reform, as dreamed up by

politicians, has been tried many times during the

last half century. It has failed every time.

Handout Page 15

Poverty and student achievement: Are we comparing the wrong groups?

Valerie Strauss – The Answer Sheet – May 9, 2013

Earlier this week I published a piece by UCLA Professor and author Mike Rose titled, “Leave No Unwealthy

Child Behind,” in which he discusses how economic inequality is reflected in educational achievement.

Here’s a response from Robert Bligh, former general counsel of the Nebraska Association of School Boards.

Bligh’s research interest involves the efficacy of the school reform efforts promoted by the Elementary and

Secondary Education Act since its original adoption in 1965. He served as assistant professor at Doane

College and was editor and publisher of the Nebraska School Law Reporter.

Robert Bligh

I write in response to UCLA Professor Mike

Rose’s “Leave No Unwealthy Child Behind.” I

want to suggest a somewhat broader view of the

problem. No rational person can question the

overwhelming relationship between a financially

impoverished childhood and a strong tendency to

fail in school.

Unfortunately Professor Rose’s commentary

seems to suggest that the sole cause of the

problem is poverty and that it is unrelated to the

behavior of the failed students’ parents.

Such a conclusion ignores the fact that millions

of impoverished students succeed academically

every day. This is very probably because their

parents have gone to considerable trouble to raise

their children despite the difficulties created by

numbing poverty.

Any child, impoverished or affluent, who is

treated like a treasure rather than a nuisance

enters kindergarten with a built-in advantage.

When we are silent about the fundamental impact

of failed families, our silence is an insult to the

heroic families who refuse to allow financial

poverty to become academic destiny for their

children.

If we really want to use scientific comparisons

to identify approaches that could be used to help

children succeed in school – and in life – perhaps

we should examine the possibility that we are

comparing the “wrong” groups of children.

Perhaps we should stop comparing children

living in poverty with children not living in

poverty. Perhaps we should begin looking more

closely at two different groups of poor children.

Consider research to identify the most

meaningful differences between the households of

(a) poor kids who fail academically and (b) poor

kids who succeed academically. That would do at

least two good things:

(1) It would remind all of us that strong

(responsible, adult, humane, caring, childoriented, nurturing, etc.) families tend

strongly to generate academically successful

children even in the face of financial poverty,

and

(2) It would give us a list parenting skills (and

other non-school factors) that, when

steadfastly and humanely applied even in

financially poor families, tend to produce

kindergartners who show up on the first day

of school without academic achievement gaps

already well-established. We know that

teachers can successfully teach such children.

Each child’s life includes about 50,000 hours

between conception and the first day of

kindergarten. Each student spends only about

14,000 hours in classrooms between kindergarten

and the end of 12th grade.

Consider the Stanovich “Matthew Effects”

explanation of the delayed acquisition of reading

skills. Earlier learning failure generates later

learning failure.

It seems undeniable that what happens (that is,

what is experienced, learned and suffered by a

child) during the first 50,000 hours of life largely

determines the academic success or failure during

following the 14,000 hours of formal schooling.

I admit that this sounds as if I am “blaming”

the parents for the academic failure of their

offspring and, thus, violating a cherished political

taboo. For a minute, forget “blame” and its

political baggage.

Consider “cause” and its scientific significance.

If our emotional distaste for the term “blame”

prevents us from conducting an intellectual

search for “cause” (as it has for the last five

decades), then I would argue that we become

morally responsible for the ensuing damage.

The solution to this horrific problem is not

hiding in our classrooms. If it were, we would

have found it by now. We are academically and

morally obligated to look elsewhere.

Impoverished

parents

of

academically

successful children are heroes. We should

examine the aspects of their behavior that make

them so successful at being parents.

It would not only give them the honor they

deserve, but it might give us a map of the

pathway to academic success for all children

trapped in poverty.

Handout Page 16

Are teachers born and raised rather than trained?

Valerie Strauss – The Answer Sheet – November 13, 2012

Who should teach? Robert Bligh, former general counsel of the Nebraska Association of School

Boards, looks at the issue in the context of the previous post about historian David McCullough’s

comments about who should teach and who shouldn’t. (He said no professional teacher should

have an education degree.) Bligh’s research interest involves the efficacy of the school reform

efforts promoted by the Elementary and Secondary Education Act since its original adoption in

1965. He served as assistant professor at Doane College and was editor and publisher of the

Nebraska School Law Reporter.

By Robert Bligh

I am intrigued by the comments of David

McCullough about the training of K-12

teachers. I have several reactions:

(1) I suspect that a successful teacher

training program produces good teacher

candidates

because

of

the

personal

characteristics of the prospective teachers it

admits and graduates. Indeed, I have begun

to suspect that most of what goes into making

a successful K-12 teacher is in place before the

teacher-to-be

becomes

a

kindergarten

student. I would say that a good teacher is

born (with the right genes) and raised (in the

right household), rather than “trained” or

“educated.”

(2) Pure academic intelligence (whatever

that might be) is probably the least important

characteristic in an effective K-12 teacher.

Certainly there are plenty of extremely bright

teachers, but teacher contributions to K-12

students are not influenced much by pure

teacher academic ability.

(3) Teacher personality traits (humane

motivations, patience, sensitivity, tolerance

for many circumstances that most people

cannot tolerate) mean much more than mere

academic ability. K-12 teaching is more of a

nurturing role than an intellectual role.

Teachers at every level who “fail” with bad

students are the same teachers who

“succeed” with good students.

(4) I wish that all teacher training

programs would simply acknowledge that

the most important thing they do to produce

effective teachers is deciding (a) who they let

into the program and (b) who they let

graduate. If well-chosen teacher candidates

are able to demonstrate that they are smart

enough to graduate from college, their

success in the K-12 classroom will be directly

proportional to the quality of students they

are given to teach.

(5) The common judgment of the impact

of teachers is wrong. The idea that formal

education – preschool or K-12 – can be an

effective substitute for a healthy nurturing

family is nonsense. Children spend less than

9 percent of childhood in school and more

than 91 percent of childhood someplace else.

Every child lives 50,000 hours between

conception and the first day of kindergarten

and spends less than 14,000 hours in a

classroom between the start of kindergarten

and the end of Grade 12.

(6) Students who are well-raised –

especially during the prekindergarten period

– tend strongly to succeed in school

irrespective of the “quality” of their teachers.

Students who are not well-raised —

especially during the prekindergarten period

— tend strongly to fail in school irrespective

of the “quality” of their teachers. This

outcome occurs in every state, in every school

district and in every classroom.

(7) Expecting education to repair the

developmental damage inflicted upon

children by preschool life in inadequate

households has been a uniform and universal

failure since it began to become politically

popular in 1965. Children who fail

academically do not need better teachers and

better schools. They need better childhoods.

Handout Page 17

Midlands Voices: Nebraska Could Use Help With Pre-K

Bruce Lesley & Carolyn D. Rooker – Omaha World-Herald – June 17, 2013

[Rob Bligh Comments]

In America, a child’s ability — not the

circumstances of birth — should determine

his or her future. But today, a family’s

income has everything to do with whether

children

succeed.

Good-quality

prekindergarten education can make all the

difference.

[That is a premise that should be proved

rather than merely believed as a matter of

faith. America has been repeating the

mistake of “faith instead of proof” with K12 education for the last five decades and

has nothing but failure to show for it.]

By age 5, just 48 percent of poor children

in America are ready for school, compared

with three-fourths of children from families

with moderate and high incomes. Once kids

fall behind, the research shows they’re

much less likely to catch up. A student from

a poor family who cannot read at grade

level by third grade is 13 times less likely to

graduate from high school.

[It is not the poverty that is the cause. It

is the inadequate families. Millions of

financially impoverished children succeed

academically every year because their

parents are very good at being parents

despite the numbing burdens of financial

poverty.]

And the consequences are felt in

communities all over Nebraska. About 2,000

kids drop out of Nebraska high schools

every year. And every time we fail to

graduate a child from high school, the

foregone tax revenue and increased costs of

health care, criminal justice and other

public expenditures total nearly $300,000.

[The problem is real, it is very large and

it is growing. Our solution must not be

based merely on hope and it must not be

limited by our squeamishness about even

acknowledging the role of inadequate

families.]

What’s the problem? Money. A year of

privately funded pre-K costs about as much

as a year of college tuition at a public

university. And while many children in

low-income families attend Head Start or

other publicly funded pre-K, these

programs don’t have the funding they need

to serve all the children who qualify. So

when it’s not available, kids are left behind.

[The kids that need the help are not

“left” behind. Thanks to the inadequate

households in which they spend 50,000

hours

between

conception

and

kindergarten, they start out behind and

they never catch up. The last half century

has demonstrated that K-12 schools cannot

repair this developmental damage. There is

no evidence that pre-school can do any

better.]

Children in middle-income families also

feel the impact when incomes are too high

for Head Start but nowhere near enough to

cover the high cost of a private pre-K. As a

result, just under half of middle-income

children attend publicly subsidized pre-K

— usually financed through states or school

districts. But these opportunities are also

underfunded, leaving many middle-income

children behind.

[Is this a claim that children of the

affluent who succeed in school do so

because they attend “high cost . . . private

pre-K” programs? I would be astonished to

learn that anything approaching a majority

of children from affluent families attend

such programs. Indeed, it seems far more

likely that an overwhelming majority of

academically successful children from

affluent families, from “middle-income”

families and from impoverished families

never see the inside of any preschool

program.]

Handout Page 18

These inequities hurt all of us. They

strain our public education system, making

K-12 education more about helping kids

catch up than challenging all students to

pursue academic excellence. And when kids

fail to reach their potential, the result is

lower lifelong productivity and higher

taxpayer costs for law enforcement, health

care and welfare.

[This makes it all the more important

that we deal honestly and openly with the

cause of the problem. The cause of children

who show up at kindergarten unprepared

to succeed academically is not the absence

of preschool programs. The cause is the

absence of parents who act as if their

children are a miraculous treasure rather

than a bothersome nuisance.]

Solving this problem boils down to two

relatively straightforward requirements:

affordability and quality. High-quality early

education doesn’t matter if it doesn’t reach

the kids who need it most, so solving this

problem means making pre-K affordable.

We also must ensure the quality of pre-K

educational opportunities so all kids get

real educational benefit and taxpayers get

real value for their dollar.

[There is no reason to believe that

putting unraised children in preschool will

be any more successful than putting them

in K-12 schools has been for the last five

decades. The problem is not pedagogical.

It’s parental.]

Nebraska has already recognized the

importance of affordability and quality in

early childhood education. This year, the

Legislature took an important step toward

improving the child care subsidy program

by establishing a quality rating system for

large, publicly funded child care centers.

Recognizing that affordability is important

too, Nebraska increased the eligibility level

so more families are able to access goodquality child care.

[As a remedy for the developmental

damage inflicted on innocent children by

bad quality parental care, “good-quality

child care” is equivalent to taking an aspirin

for bullet wounds.]

But Nebraska’s economic competition

isn’t coming from Connecticut and Indiana.

It’s coming from China and India. This is a

national problem, and our leaders in

Congress must craft a national strategy. A

federal-state partnership would provide the

federal funding necessary to make pre-K

affordable for every child. And quality

would be ensured, because federal funding

would be limited to providers meeting

evidence-informed quality standards.

[If the “national strategy” that “Congress

must draft” does not deal effectively with

the households that produce these innocent

victims, the result in the future will be

indistinguishable from the failure of the

past.]

We know it won’t be easy, but can no

longer ignore the evidence that some of the

most important learning takes place in the

years before kindergarten. That expensive

delusion has already cost children and

taxpayers too much. A child’s potential, not

a parent’s income, should define the limits

of success in school and life.

[Expensive delusion, indeed! What is

damaging these children is not low level

parental income. What is damaging these

children is low quality parental care. If we

cannot squarely face the real cause, we will

simply add to the failure we have

steadfastly accumulated since this problem

was officially dumped on America’s K-12

schools with the passage of the useless and

wasteful federal Elementary and Secondary

Education Act in 1965. – Rob Bligh]

Handout Page 19

© Copyright 2026