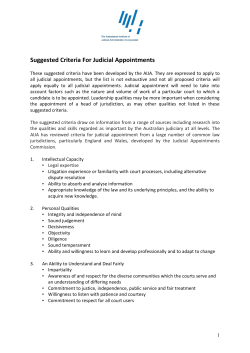

View PDF - Cornell Law Review