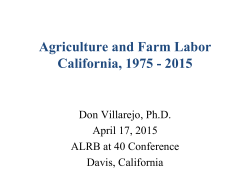

in the 1940s - `Doc` Dockery