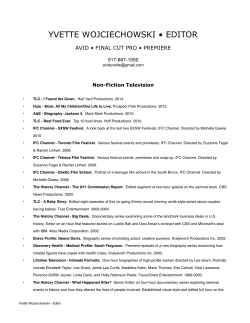

2008 AP English