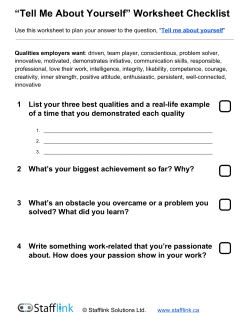

relationship between passion for work and the subjective career