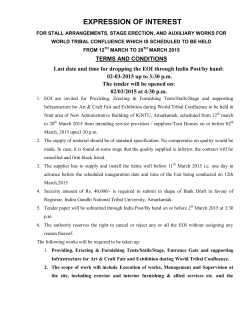

domestic arrangements of middle class turkish families reproduced