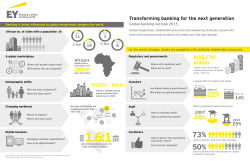

The Role of Foreign Banks in Trade