Read and Save Printable PDF

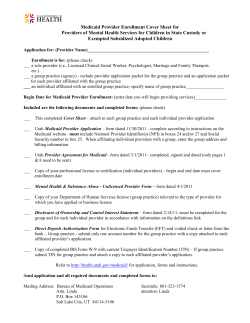

h e a lt h p o l ic y b r i e f 1 w w w. h e a lt h a f fa i r s .o r g Health Policy Brief u p dat e d m ay 1 5 , 2 0 1 5 Medicaid Primary Care Parity. For 2013 and 2014, the federal government raised payment rates to Medicaid primary care providers. Only some states plan to extend the rate increase. what’s the issue? Section 1202 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) required states to raise Medicaid primary care payment rates to Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014, with the federal government paying 100 percent of the increase. This provision—often referred to as “Medicaid primary care parity” or the “Medicaid primary care fee bump”—was intended to encourage primary care physicians to participate in Medicaid, particularly in the face of an expected increase in enrollment as a result of the ACA’s expansion of the program. Federal lawmakers failed to reauthorize the fee bump during the 113th Congress, ending in December 2014. As a result, states must decide whether to revert to previous primary care payment levels or continue at a higher level but without the benefit of the enhanced federal match. As of January 1, 2015, sixteen states and the District of Columbia had decided to continue paying enhanced rates, while thirty-four states had declined. ©2015 Project HOPE– The People-to-People Health Foundation Inc. 10.1377/hpb2015.5 Although the program is over, the debate about whether it worked—and should, therefore, be reinstated in some form—continues. Evaluators have been challenged by the pro- gram’s later-than-planned start and short duration, which many believe made it impossible to detect program impacts. Another challenge to measuring the program’s impact is that it was intended to improve access to care—a variable that is difficult to measure directly. Evaluators’ focus has been primarily on provider participation, which may be an incomplete proxy for access. Finally, program evaluation is hampered by the difficulty of isolating the impact of the payment increase from the impact of hundreds of other changes made in both public and private insurance and delivery systems under the ACA. This policy brief describes the Medicaid primary care fee bump, the rationale for the program, and the details of its rollout. Next, the brief explores evidence of the program’s impact, outlines stakeholders’ views on both sides of the debate, and concludes with some thoughts about how the program could be improved or modified in the future, if it is to be continued at the national or state levels. what’s the background? The Medicaid primary care fee bump was intended to encourage primary care providers to participate in Medicaid. Primary care ac- h e a lt h p o l ic y b r i e f “The program’s goal was to ensure access to primary care for Medicaid recipients by increasing provider participation.” 2 m e dic a i d p r i m a r y c a r e pa r i t y cess problems—long considered a challenge in Medicaid—may be exacerbated by Medicaid expansion. Prior to the ACA’s coverage expansions, average monthly Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment was nearly fifty-eight million. In April 2014 the Congressional Budget Office projected that an additional seven million people would gain coverage through Medicaid and CHIP in 2014, increasing to eleven million in 2015, and holding steady at twelve to thirteen million from 2016 to 2024. Low Medicaid payment rates are often cited as a reason for low provider participation and, consequently, reduced access to care for beneficiaries. However, research has not firmly established a positive correlation between Medicaid payment rates and access. For example, a 2005 study found that higher payments were correlated with some measures of patient access (the probability of having a usual source of care, the probability of adults’ having at least one visit to a doctor, and positive assessments of the health care received by adults and children), but not with others (the probability of receiving preventive care or the probability of having unmet needs). In contrast, in a 2012 study published in Health Affairs, researchers found that a 10-percentage-point increase in the ratio of Medicaid to Medicare fees correlated with a 4-percentagepoint increase in acceptance of new Medicaid patients. The June 2013 Report to Congress from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) provides a succinct summary of this literature. Despite the lack of consistent research findings supporting a link between Medicaid payment and patients’ access to care, many stakeholders believe that payment must be an important lever in improving access. In 2012 Medicaid primary care fee-for-service (FFS) payment rates averaged 59 percent of Medicare fee levels for the same services, across all states. The Medicaid/Medicare primary care fee ratio varied widely by state, with some state Medicaid programs (California, Florida, Michigan, New York, and Rhode Island) paying less than 50 percent of Medicare fees, and another thirty states paying no more than 75 percent. (It is important to note, however, that in several of the states with very low FFS rates for primary care, the majority of beneficiaries are actually enrolled in Medicaid managed care, for which primary care payment rate data were not available.) what’s the policy? Providers eligible for the increased payment included those who self-attested to a specialty or subspecialty designation of family medicine, general internal medicine, or pediatric medicine. Providers self-attested to this designation based on board certification or if they could show that 60 percent of all Medicaid services they billed were for the procedure codes to which the fee bump applied. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants working in primary care were eligible if working under the supervision of an eligible physician. The ACA specified 146 health care services to which the fee bump applied. These included evaluation and management services with procedure codes 99201–499 and vaccine administration services for children with procedure codes 90460–1 or 90471–4. The size of the increase in payment varied by state, as some states’ Medicaid primary care FFS rates were closer than others’ to Medicare parity before the law’s passage. The fee bump was effective January 1, 2013. However, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) did not release a final rule on program implementation until November 2012, causing states to make some of their 2013 parity payments retroactively. The primary care fee bump applied to both FFS Medicaid and Medicaid managed care. While increasing a FFS payment rate is typically straightforward, increasing a capitation payment (a uniform amount paid to the managed care company for each patient, no matter how many services they use) can be challenging because the payments may cover not only primary care but a wide range of other services. Technical difficulty in setting and administering enhanced capitation rates contributed to delays in program implementation. Researchers from the Center for Health Care Strategies conducted extensive stakeholder interviews about the fee bump, reporting that establishment of the managed care rates required “lengthy preparation and ramp-up periods, as well as drawn-out negotiations with [CMS].” In fact, the researchers reported that primary care providers working in states that contract with Medicaid managed care plans had a much less positive view of the fee bump than did FFS providers, likely because of the significant delay in implementation. Another factor contributing to late and slow program implementation was the requirement h e a lt h p o l ic y b r i e f 16 states and D.C. As of January 1, 2015, sixteen states and the District of Columbia had decided to continue paying enhanced rates, while thirty-four states had declined. 3 m e dic a i d p r i m a r y c a r e pa r i t y that providers must self-attest to program eligibility. States had to develop and administer the self-attestation process, delaying them in reaching out to providers with information about the new program. Some stakeholders felt that when outreach did occur, it was limited only to those physicians already accepting Medicaid. Others believed that outreach to physicians and other providers was too limited in general, resulting in providers’ not knowing how to self-attest or not being aware that they were required to do so. Despite delays in program implementation, the federal government had paid out $7.1 billion under the program through September 30, 2014. States have up to two years to submit claims for federal reimbursement, and total spending is expected to reach about $12 billion in total. To continue Medicaid primary care parity, Congress would have had to reauthorize the program by December 2014. It did not. An October 2014 survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that if Congress did not act, fifteen states planned to take up the slack, continuing to pay increased primary care fees using a combination of state and federal funds. (The latter will be provided at the state’s customary Medicaid federal matching rate, which, in all cases, is far lower than the 100 percent “match” available under the expired fee bump program.) At that time, twenty-one states and the District of Columbia said exhibit 1 State Decisions On Medicaid Pay Bump, As Of January 1, 2015 Will not continue Will continue source Janet Weiner, Simon Basseyn, and Chris Colameco, Bumped-Up Medicaid Fees for Primary Care Linked to Improved Appointment Availability (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, January 21, 2015). that they would not continue to pay the higher rates, and fourteen states were undecided. In December 2014 the Urban Institute estimated that if none of the forty-nine states it studied nor the District of Columbia elected to continue the fee bump on its own, the demise of the program would result in an average 42.8 percent reduction in primary care fees for Medicaid providers. (Tennessee was excluded from the study because it does not have a FFS component to its Medicaid program.) The predicted reduction would vary widely by state because—as noted—some states’ primary care fees were already much closer to Medicare rates than were others’ before the program started. The researchers segmented states into three categories: those that (as of October 2014) had indicated they did not plan to continue the increase with state funds; those that did intend to do so; and those that were still undecided. Not surprisingly, the states intending not to continue with the increased fees were those that had received the greatest federal bump under the program and were, therefore, facing the largest hole to be filled in with state dollars. In January 2015 researchers from the Urban Institute and the University of Pennsylvania contacted the states that had previously reported being undecided about continuing the fee bump. Of those, only one (Montana) had moved into the “continue” column, bringing the total number of continuing states to sixteen, plus the District of Columbia—which had reversed its earlier decision not to continue (see Exhibit 1). The rest had decided to decline, bringing the total number of declining states to thirty-four. what’s the debate? The Medicaid primary care parity program has ended, but the debate about its effectiveness—and whether it should be replicated in some form in the future—continues. Again, the program’s goal was to ensure access to primary care for Medicaid recipients by increasing provider participation. If the program achieved that goal (which is, as yet, unknown), we may see a reduction in primary care provider participation and a concomitant reduction in beneficiary access, which may, ultimately, lead to worse health outcomes. On the other hand, some stakeholders have argued that instead of increasing primary care provider participation, the program mostly benefited providers who were already participating, and h e a lt h p o l ic y b r i e f it’s not clear that this is an effective route to improving access. “In some cases, states would like to continue the program but simply do not have enough resources to do so.” 4 m e dic a i d p r i m a r y c a r e pa r i t y It may ultimately be possible to settle these questions empirically, and research is underway. Efforts to identify the program’s impacts are hampered by the fact that it was in place for such a short period of time and was implemented in different ways and at different times across states. Despite these challenges, however, a few researchers have begun to publish results. Some have attempted to measure patient access directly, while others have used provider participation as a proxy for access. Review of Evidence In a February 2015 evaluation of the fee bump, researchers from the Urban Institute and the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics conducted a “secret shopper” study in ten states to see whether access to primary care had improved. “Access” was defined as “appointment availability for Medicaid enrollees seeking newpatient primary care appointments at physician offices that participated in Medicaid.” The availability of primary care appointments in the Medicaid group increased by 7.7 percentage points after the fee bump was implemented, while there was no increase in availability for the privately insured patients. The larger the fee bump in a given state, the larger the increase in Medicaid primary care appointment availability. Every 10 percent increase in reimbursement rates led to an increase in appointment availability of 1.25 percentage points. (Notably, all ten states in the study mandate managed care for adult Medicaid enrollees, so it may not be possible to extrapolate these findings to FFS Medicaid environments.) This study suggests that the fee bump did improve access, but it did so by increasing the capacity of primary care providers already participating in Medicaid. Of necessity—because the researchers compared appointment availability pre– and post–fee bump—they limited their analysis to practices that participated in Medicaid both before and after the fee increase. They were, therefore, unable to draw conclusions about whether the program brought new providers into Medicaid. Other research on the program’s effectiveness has been more qualitative, with findings based on stakeholder interviews. MACPAC conducted a series of semistructured interviews with Medicaid officials, plan administrators, and provider organizations in eight states. In its March 2015 Report to Congress, MACPAC noted that few physicians completing the attestation to participate in the program were new to Medicaid. In the states MACPAC studied, “the payment increase had little to no effect on Medicaid provider participation rates.” In addition, interviewees in six of the eight states reported no change in primary care service use after the program’s implementation. Researchers from the Center for Health Care Strategies also conducted interviews with policy experts and staff from selected state Medicaid programs, health plans, and provider organizations, asking (among other things) whether those states had seen an increase in provider participation. The results were mixed, and the researchers did not draw any conclusions. However, they did note that provider participation is problematic as a measure of the program’s success. There simply has not been enough time to study the program’s impact on provider enrollment trends, and any observed increase in provider participation—such as those reported in Ohio and Connecticut—could be as a result of factors other than the fee bump. The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation within the Department of Health and Human Services has contracted with the RAND Corporation to conduct an evaluation of the fee bump program. The researchers will use office visit claims data from Medicaid and other payers to analyze the program’s impact on providers’ patient mix—arguably a better measure of access than is provider participation. Advocates on Both Sides While evidence of the program’s impact, or lack of impact, on access is limited, there are nevertheless advocates on both sides of the debate. Many of those in favor of continuing increased primary care rates believe that the program’s demise will inevitably lead to reduced access for Medicaid beneficiaries. Some say that the two-year time frame of the program was too short to determine whether the policy worked, and more time is needed. Prominent physicians groups, including the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians, have been vocal in their support of the program. These groups contend that even if the program did not bring new physicians into Medicaid, it allowed existing Medicaid primary care pro- h e a lt h p o l ic y b r i e f viders to maintain their previous levels of participation, which were unsustainable under the old rate structure. In an April 2014 survey of members of the American College of Physicians, 40 percent said they would accept fewer Medicaid patients in 2015 if the fee bump expired, and 6 percent said they would stop participating in Medicaid altogether. 12 billion $ Total federal spending for the fee bump is expected to reach about $12 billion in total. 5 m e dic a i d p r i m a r y c a r e pa r i t y In addition, according to MACPAC, some of the states continuing the fee bump said they were doing so—despite not being able to quantify its impact—because they felt there were other benefits, such as improving relationships and generating goodwill between providers and the Medicaid agency. A state’s decision not to continue the fee bump does not necessarily signal lack of confidence in the program’s ability to achieve important benefits. Instead, in some cases, states would like to continue the program but simply do not have enough resources to do so, or must consider cuts in other programs to finance the increased fees. Stakeholders who see the expiration of the fee bump in a more neutral light seem to fall into two camps (and some are in both): Those who believe the program was poorly designed to achieve its goal, and a better solution may be available; and, those who do not believe that the payment and access problems are as severe as reported, especially in Medicaid managed care (as opposed to FFS). One prominent expert on the side of allowing the fee bump to expire was Matt Salo, president of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. Salo told Health Leaders Media that “many states believe the Medicaid parity law was poorly designed, had little effect on care delivery while it was operating, and won’t be missed after it’s gone.” Salo also contends that in most states, the vast majority of Medicaid primary care is delivered under managed care programs, where, he says, “the docs are [already] getting paid a lot better.” While not necessarily taking a position on the fee bump either way, the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured published data suggesting that the Medicaid access problem may not be as severe as many believe. The commission’s Julia Paradise noted in an interview last year that “while primary care physicians participate less in Medicaid than in private insurance, most primary care physicians do accept new Medicaid patients. Surveys indicate that a small minority of Medicaid beneficiaries have difficulty finding a general doctor or provider, and core measures of access to primary care are comparable between Medicaid and private insurance among both children and adults.” what’s next? At the January 2015 MACPAC meeting, the commissioners discussed the program’s impact and whether or not they would continue to track it. At the moment, it does not appear that Congress will take up the issue of increasing Medicaid primary care fees in the near future. In the meantime, as noted, sixteen states and the District of Columbia will continue the fee increase, while thirty-four states will not. Commission chairperson Diane Rowland says that this situation provides a “natural experiment”—an opportunity to determine more definitively the impact of increasing Medicaid primary care fees. Other commissioners concurred. The general tenor of the discussion was that increasing provider participation is complex, and fees are only one piece of the puzzle. Several commissioners noted that changes in the way providers are organized may also have an important impact on Medicaid participation, specifically calling out declining rates of independent practice and the accelerated formation of accountable care organizations. Along similar lines, researchers at the Center for Health Care Strategies have noted the shortcomings of designing the program around a FFS model. With so many public and private payers adopting value-based payment models, the fee bump program was tied to an old pay-for-volume paradigm that many believe is outdated. A more forward-thinking program would allow states to use enhanced federal funding for primary care to reward practice and quality improvement. With sixteen states and the District of Columbia continuing to pay enhanced fees, there will likely be important variations among those programs’ goals and features, providing another natural experiment around the most effective use of payment as a lever to improve access to primary care in Medicaid. n h e a lt h p o l ic y b r i e f About Health Policy Briefs Written by Laura Tollen Consulting Editor Health Affairs Editorial review by Benjamin Finder Senior Analyst MACPAC Tricia McGinnis Vice President, Program, and Director, Delivery System Reform Center for Health Care Strategies Rob Lott Deputy Editor Health Affairs Tracy Gnadinger Assistant Editor Health Affairs Health Policy Briefs are produced under a partnership of Health Affairs and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Cite as: “Health Policy Brief: Medicaid Primary Care Parity,” Health Affairs, updated May 15, 2015. Sign up for free policy briefs at: www.healthaffairs.org/ healthpolicybriefs m e dic a i d p r i m a r y c a r e pa r i t y 6 resources American Academy of Family Physicians, MedicaidMedicare Parity (Leawood, KS: AAFP, 2015). Maia Crawford and Tricia McGinnis, Medicaid Primary Care Rate Increase: Considerations Beyond 2014 (Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, September 2014). Department of Health and Human Services, “Medicaid Program; Payments for Services Furnished by Certain Primary Care Physicians and Charges for Vaccine Administration Under the Vaccines for Children Program; Final Rule,” Federal Register 77, no. 215 (2012): 66670–1. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP: Chapter 8: An Update on the Medicaid Primary Care Payment Increase (Washington, DC: MACPAC, March 2015). Julia Paradise, Medicaid Moving Forward (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, March 2015). Daniel Polsky, Michael Richards, Simon Basseyn, Douglas Wissoker, Genevieve M. Kenney, Stephen Zuckerman, and Karin V. Rhodes, “Appointment Availability after Increases in Medicaid Payments for Primary Care,” New England Journal of Medicine 372, no. 6 (2015): 537–45.

© Copyright 2026