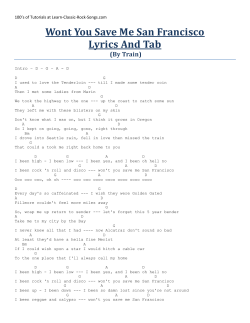

O