Prevalence of Refractive Errors in Primary School Children in a

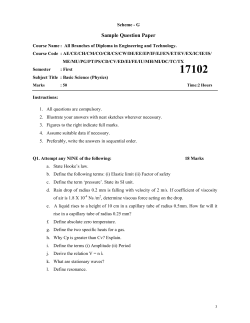

Prevalence of Refractive Errors in Primary School Children in a Rural Community in Ebonyi State of Nigeria Year : 2013 | Volume : 18 | No : 3 | Page : 017-034 Date of Web Publication 09-June-2015 Abstract Background: Globally, refractive error is a common cause of visual impairment in the paediatric age group. However, no previous vision screening study among primary schools children has been reported in Ebonyi State, South-Eastern Nigeria. This study aimed to screen primary school children in two rural primary schools in Nchokko Community of Igbeagu Izzi, Ebonyi State for refractive errors Subjects and Methods This was point prevalence, cross- sectional study of all primary school children in the two primary schools at Nchokko community of Igbeagu village of Izzi local government area of Ebonyi State. The study population consists of all pupils present during the school eye health visit to this community on the 6th of March 2012. Results There was a total of 213 pupils comprising of 107 males and 106 females (Ratio, 1:1) ages ranged from 5-15 years with a mean age of 9.6 ± 2.7 years. Refractive error was found in 2 patients (0.9%). Conclussion The Prevalence of Refractive Error in the two rural primary schools at Nchokko community of Igbeagu village of Izzi Local Government Area of EbonyiState.was 0.9%. Key words: Nigeria, Refractive error, Rural, school children Introduction Globally, visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive error is a significant cause of poor vision in children.1-2 It is estimated that 12.8 million children aged 5 – 15 years are visually impaired due to uncorrected refractive error. 3 Uncorrected refractive error (RE) remains a public health problem among different population groups, thereby warranting its recognition as a priority area for intervention by the Vision 2020- The Right to Sight4. Uncorrected RE is one of the leading cause of low vision and the second cause of blindness.3 In children, the uncorrected refractive error can hinder education, as optimal vision is needed for proficiency in learning.5 Refractive Error Study in Children (RESC) from Chile, 6 China 7 and Nepal 8 documented that refractive error (RE) was responsible for 56.3%, 89.5% and 56% of reduced vision respectively. Along with cataract, trachoma, onchocerciasis and vitamin A deficiency, refractive errors have been listed, among eye problems whose prevention and cure should provide enormous savings and facilitate socio-economic developments. 9Children who are visually impaired must overcome a lifetime of emotional, social and economic difficulties, which also affect the family and society.10 Loss of vision in children influences their education, employment and social activities.10 Vision has an essential role in a child’s development, and a visual deficit is a risk factor not only for altered visiosensory development, but also for overall socioeconomic status throughout life11. In most instances, children do not complain of their visual difficulties by themselves. Timely screening for the early detection of eye and vision problems in children is vital to avoid lifelong visual impairment. Early detection provides the best opportunity for effective treatment10. The benefit of regular eye screening in children that includes a comprehensive eye examination has been recognized worldwide, including in developed economies12. Early corrective measures for deficits detected would greatly assist in reducing childhood blindness and related morbidity. School-age children (6-15 years) represent 20–30% of the total population in most low and medium income countries(LMICs)13. For Nigeria, this translates to 20–30 million children. In some states in Southern Nigeria, 80% of children attend school and can, therefore, be reached by healthcare programs14. Therefore, school children are an important, large target group for early detection of eye diseases and prevention of blindness.15 Vision screening involves searching for unrecognized eye disease or defect using rapidly applied tests, examinations or other procedures for apparently healthy individuals. 13,16 A screening test is not intended to be a diagnostic test; it is only an initial examination. Those who are found to have ocular problems are referred to an ophthalmologist for further diagnostic work-up and treatment. In this study, vision screening was carried out in all the pupils in the only two rural primary schools, with a view to determining the burden of refractive errors among this rural paediatric population. This study will provide data to government educational and health policy makers for planning and implementing an effective school Eye Health Programme for the state. Methods This was a point prevalence, cross- sectional study of all school children present in the two primary schools at Nchokko community of Igbeagu village of Izzi local government area of Ebonyi State at the time of study. Context Izzi Local Government Area has its headquarters at Iboko. It has a total population of 261, 410[9]. There are 25 communities in Izzi LGA. Igbagu Development Centre is one of the newly created development centres in Izzi LGA. It is about 20 kilometers from Abakaliki, the state capital. Four out of the 25 communities in Izzi LGA make up the development centre. All the four communities serve as the catchment area for the Primary Health Care Centre of Ebonyi State University Teaching Hospital, now known as Federal Teaching Hospital Abakaliki (FETHA). Nchokko community, which is the location of this study, is one of the communities in Igbeagu Development Centre of Izzi Local Government Area of Ebonyi State. The Department of Community Medicine of the Ebonyi State University/Federal Teaching Hospital, has the development centre as its Primary Health Care (PHC) Practice Area.This is used for the training of medical students and resident doctors in primary health care and also provision of preventive and curative clinical services. The Department of Ophthalmology also uses that primary health care centre for its community ophthalmology programmes. Study Population The study population consists of all pupils present during the school eye health visit to the only two primary schools of the community on the 6th of March 2012. Permission to carry out the study This school eye health visit was arranged by the Department of Community Medicine of Ebonyi State University (EBSU) as part of their Rural Health Exposure for Medical Students. The department of ophthalmology of EBSU was invited to conduct the eye screening part of the program. Permission to carry out the study was sought for and obtained from, the Faculty of Clinical Medicine and the University management, who also provided some of the logistics such as transport. Each participating community /school was visited two weeks before the screening day, and permission to do the study sought and obtained from the community leaders and Head teachers. Procedure Outdoor visual acuity assessment for each eye was done by an ophthalmic assistant for all the school children who were present during the screening. This was done using the standard Snellen eye-test chart placed at 6 metres. Visual acuity level is taken at the line of complete identification of the line alphabets. Those with visual acuity of 6/9 or less were presented with a pinhole and the test repeated. Improvement of visual acuity with pinhole was considered as a refractive error. External eye examination was performed using a pen torch and a simple magnifying head loupe. Posterior segment studies were also done for each pupil using a direct ophthalmoscope in required cases. Those who needed further evaluation and/or treatment were referred to the teaching hospital of the University. Data Analysis Data were entered into, cleaned and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA), and reported as frequency distributions, percentages and means ± standard deviation. Ethics Approval Ethical approval consistent with the tenets of 1964 Helsinki Declaration on research involving human subjects was obtained from Ebonyi State University’s Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board). The study was adequately explained, and the refusal of participation by parents, teachers or children was respected. Results There was a total of 213 pupils; ages ranged from 5-15 years with a mean age of 9.6 ± 2.7 years. There were 107 males and 106 females (Male to female ratio of 1:1). Refractive error was found in 2 pupils (0.9%). See tables 1 and 2. Discussion Vision screening and refractive services for school children have been recommended by WHO as a useful strategy for prevention of avoidable childhood blindness. 17 Since most children with uncorrected refractive error are asymptomatic, screening helps in early diagnosis and timely interventions.Thereforethis strategy has been found to be a very useful measure 18 The prevalence of refractive error varies widely in children from 50% in Singapore, 36.7% in Hong Kon,19 14.8% in Malaysia,20 12.8% in China,21 11.6% in Uganda22to less than 1% in Tanzania.23In Malaysia20 the study population comprised 70.3% Malay, 16.5% Chinese, 8.9% Indian and 4.3% other ethnicity. The prevalence of uncorrected, presenting and best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/40 or worse in at least one eye was 17.1%, 10.1% and 1.4% respectively. Among the eyes with reduced vision, refractive error was the cause in 87.0%, amblyopia in 2.0%, other causes in 0.6% and unexplained causes in 10.4%. Over half of the children that needed corrective spectacles did not have them. The prevalence of refractive errors found in this study was low (0.9%). Similar studies have confirmed low prevalence of refractive errors in rural schools. Chuka-Okosa in a study of refractive errors in rural school children in Nkanu West LGA of Enugu State, South-Eastern Nigeria, reported a prevalence of 1.97%.24 Ajaiyeoba et al in another rural community in South Western Nigeria observed a refractive error prevalence of 0.87%.25 In Yenegoa local government Area of South-south Nigeria, Opubiri et al. reported a prevalence rate of 2.2 %.26 In a study by Okoye et al. at a rural primary school, Anambra state Nigeria, the prevalence of refractive error was found to be 0.7%.27 Relatively higher prevalence values have been reported from studies done in some cosmopolitan cities of Nigeria. Nkanga13 in Enugu Nigeria reported a prevalence rate of 7.4% and Faderin28 in Lagos reported a prevalence rate of 7.3%. These studies suggest that schools in urban centres have a higher prevalence of refractive errors than schools in rural areas. This is corroborated by Padhye et al29 in Maharastra, India, who did a comparative study of refractive error prevalence rates in urban and rural schools. In that study the prevalence in urban schools was higher than that in rural schools. The higher prevalence in cosmopolitan cities may be related to the mixed socio-economic population of a variable combination of low-, middle- and high income cadre population in such cities. An Australian study30 had suggested the influence of environmental factors such apartment stylehousing and higher population density as a reason for the difference in prevalence of refractive error between rural and urban children. Vision screening in schools is a cost-effective preventive strategy for childhood blindness. This is because the refractive error is a treatable cause of visual impairment, in most cases by mere spectacles. 22 Moreover, it mostly sets in at a younger age than other major causes of visual impairment and is responsible for a much larger number of blind years lived by a person than most other causes if left uncorrected. Although the burden of refractive errors may be lower in rural schools, the reduced availability of access to eye care services in such schools makes it as important as in urban cities to have regular vision screening programmes for these schools. This testing should involve visual acuity measurement and an eye examination by trained eye care personnel, public eye health education and training of teachers to carry out simple vision screening. The effectiveness of such a vision screening project has been reported in Maharashtra, India.In this case,the staff of community ophthalmology unit of an eye centre regularly embark on annual screening for school children both in urban and rural areas in their catchment area.29During this programme, the children at remote rural schools are examined in mobile eye units while the school teachers trained in vision screening examine students of urban schools. The aim is to identify children with a refractive error as early as possible and to offer them spectacles while those with other causes of reduced vision are referred to secondary and tertiary eye care facilities for appropriate treatment. It has been suggested that vision screening be routinely done at school entry, midway through school and at the completion of primary education to enhance early detection and treatment of eye diseases.26. This can be achieved if school eye health programmes become incorporated into primary health care as done in immunization programmes. Government and Non-governmental organizations can sponsor school eye health programmes much the same way that vaccination programmes are sponsored. Limitations Its school-based nature limits the extrapolation of the conclusions drawn from this study since a significant number of school aged children may not be in school due to poverty. Also, retinoscopy of the children would have helped to characterize the refractive errors. A large sample size, community-based design setting with retinoscopy is suggested. Conclusion This study found a prevalence of 0.9% of refractive error among the rural primary school children in Nchokko community of Igbeagu village of Izzi local government area of Ebonyi State. Nigeria. It is recommended that implementing regular vision screening of primary school children as part of primary eye care should be given priority. Also eye screening (at least visual acuity testing) should be done in schools routinely at school entry, midway through school and at the completion of primary education. This will help to identify those with a refractive error with prompt refractive correction offered to prevent life-long visual impairment from amblyopia and also to facilitate optimal learning ability. Acknowledgement We acknowledge the assistance of the medical students who collected the data during their rural posting experience in community medicine. We also recognize the support and cooperation of the two schools in Nchokko village whose pupils were studied. We also recognize the help of the Nchokko community development association as well as the village head for their cooperation during this study. Finally, we thank the Vice Chancellor of Ebonyi State University, Prof Francis I. Idike for creating the enabling environment that enabled the rural posting experience of the fifth year medical students to take place without which this study may not have been possible. Disclosure The authors declare that we have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced us in writing this article. References Ager L. Optical Services for Visually impaired children. J Comm Eye Health. 1998; 11:38–40. World Health Organisation, author. WHO/PBL/9761. Geneva: WHO; 1997. Global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. The bulletin of the World Health Organization 2008;86(1):63-70. Thylefors B, A global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. J Comm Eye Health 1998;(11):1-3. Ogbomo-Ovenseri GO AR. Refractive error in school children in AgonaSwedu, Ghana. S Afr Optom 2010;(69):86-92. Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz S, Sperduto R, Ellwein L. Refractive error study in children: results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;129(4):445-454. Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R, Munoz S, Sperduto R, Ellwein L. Refractive error study in children: results from Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;129(4):427-435. Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(4):436-444. Perks K. Screening for Disease. In: Perks K, editor. Textbook of preventive and social medicine. 19th ed. Barnasides: Bhuanot Co; 2007; pp. 115–116 1 Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of vision 2020. The Right to Sight. Bulletin WHO 2001; 79: 227-232. 2 Fazzi E, Signorini S, Bova S, Ondei P, Bianchi PE. Early intervention in visually impaired children. International Congress Series 2005; 1282: 117-121. 3 Qamar AR. Eye screening in school children: A rapid way. Pak J Ophthalmol 2006; 22(2): 79-81. 4 Nkanga DN, Dolin P. School Vision Screening programme in Enugu, Nigeria: Assessment of referral criteria for error of refraction. Nig J Ophthalmol 1997; 5(1): 34-40. 5 Abubakar S, Ajaiyeoba A.I Screening for Eye disease in Nigerian school children. Nigerian Journal of Ophthalmology 2000; 9(1): 6-9. 6 Desai S, Desai R, Desai N, Lohiya S. School eye health appraisal. Indian J Ophthalmol 1989; 37(4): 173-175. 7 The Nigerian Operation Plan for the implementation of the Vision 2020. Right to Sight Document (2007–2011) 2007:4. 8 World Health Organization. Elimination of avoidable visual disability due to refractive error Report of an informal planning meeting. pp. 6–10. WHO/PBL/00.79. 9 Tong L, Saw SM, Lin Y, Chia KS, Koh D, Tan D. Incidence and progression of astigmatism in Singaporean children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:3914-8. 10 Fan DS, Lam DS, Lam RF, Lau JT, Chong KS, Cheung EY, et al. Prevalence, incidence and progression of myopia of school children in Hong Kong. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:1071-5. 11 Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology 2005;112: 678-85. 12 Zhao J, Pen X, Sui R, Munoz SR, Spertudo RD, Ellwein I. Refractive Error Study in Children, result from Shunyi District in China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:427–435. 13 Kawuama M, Mayeku R. Prevalence of Refractive errors among children in lower primary School in Kampala district. Afr Health Sci 2002;2:69–72. 14 Wedner SH, Ross DA, Balira R, Kaji L, Foster A. Prevalence of eye diseases in primary school children in a rural area of Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:1291-7. 15 Chuka-Okosa CM. Refractive error among students of a post primary institution in a rural community in south eastern Nigeria. West Afr J Med 2005;24:62–65. 16 Ajaiyeoba A I, Isawumi MA, Adeoye AO, Oluleye TS. Prevalence and causes of eye diseases amongst students in SouthWestern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2006;5:197–203. 17 Opubiri I, Pedro-Egbe CN. Screening of Primary School Children for Refractive Error in South-South Nigeria. Ethiop J of Health Sci. 2012; 22(2): 129–134. 18 Okoye O, RE Umeh, Ezepue FU. Prevalence of eye diseases among school children in a rural south-eastern Nigerian community. Rural and Remote Health 13:2357. (online) 2013. 19 Faderin MA, Ajaiyeoba AI. Refractive errors in primary school children in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;9:10–14. 20 Padhye AS, Khandekar R, Dharmadhikari S, Dole K, Gogate P, Deshpande M. Prevalence of uncorrected refractive error and other eye problems among urban and rural school children. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;16:69–74. 21 Ip JM, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Myopia and the urban environment: Findings in a sample of 12- year old Australian School Children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49 (9): 3858-63. Table 1: Age-Sex Distribution of the pupils (n=213) Age Group Sex Total(%) Male Female 5-8 37 43 80(37.6) 9-12 57 46 103(48.3) 13-15 13 17 30(14.1) Total 107 106 213(100) Table 2: Demographic distribution of refractive errors among the pupils (n=213) Age Group 5-8 Sex Male Female 1 9-12 Total(%) 1(0.47) 1 1(0.47) 1 2(0.94) 13-15 Total 1

© Copyright 2026