View PDF - Cincinnati History Library and Archives

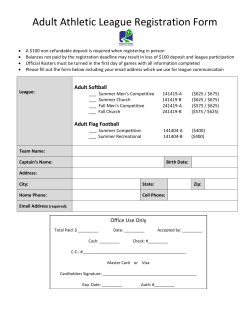

Summer 1988 Cincinnati Ballparks The Life and Times of the Old Cincinnati Ballparks Richard Miller and Gregory L. Rhodes For the newest of Cincinnati baseball fans, Riverfront Stadium is the only home the Reds have had, the only field where they have seen professional baseball played. But far removed from Riverfront, in time and space, other memories still linger across the city. Riverfront is the last of three generations of baseball parks to host Cincinnati crowds since baseball's first professional nine took the field in the West End in 1869.1 Old wooden parks dominated baseball in America from the 1860's until the first decade of the twentieth century. These were baseball's turbulent years, and the parks, like the game itself, were unstable. Like the mining boomtowns of the 1 86o's and '70's, the old parks were built hastily and built on the site of League Park at Findlay Street and Westcheaply of wood. Inside, they were much the same as rowdy ern Avenue, were Cincinnati's contribution to this second western saloons. Fights were common, with fans and players generation of parks. Crosley Field, the old park most mixing it up with each other or themselves, and the umpire Cincinnatians remember best, evolved from Redland Field was everybody's favorite target. The winning team was not in 1934; only the name was changed. There were a few always the best, but the toughest. Like the mining towns, additions and window dressings after 1934, but basically these first wooden parks were short lived and soon deserted. Crosley Field was the same cement and iron park that opened The charm of these parks was their simplicity. as Redland Field in 1912. Riverfront Stadium, opened in 1970, repreThey were neither presumptuous nor symbols of prestige and power but were mirrors of the times. The United States sents the last generation of parks, the multi-purpose stadium was still fighting Indian wars, and the country was moving for the current era. These city-owned parks, regal concrete west. America still had a cowboy mentality, even in the East, crowns with acres of parking lots and nary a knothole to and nothing reflected this more than the old wooden ballparks. peek through, are a definite swing away from the democratic They were new frontiers in American society. Such was the character of the earlier ballparks. Today, there are domes and backdrop for the old Cincinnati parks: Union Grounds stadiums; then there were the more romantic "grounds" and (1 867-1 870), Avenue Grounds (1 876-1 880), Bank Street "yards" and "orchards." Teams now play in markets and Grounds (18 81 -1 8 84), Pendleton Park (1891), and old League regions rather than cities and neighborhoods. The old baseball parks were as much a part of Park (1884-1902). Baseball came of age during the wooden the neighborhood as the cop on the beat, the parish church, ballpark era. The cut throat competition among leagues and or the corner drug store where you could stop and see a few associations for supremacy in the cities from Massachusetts innings of baseball on the way home from school or work. to Missouri ended. Teams put down roots, and baseball Daily routines, businesses, children's games, the entire folklore of the neighborhood were all shaped by the presence of became America's first truly national pastime. The sense of stability and confidence in the the park. These were the sites where heroes lived and legfuture of the game was grandly evident in the new cement ends roamed, and where one can still hear the roar of an and iron parks of the early twentieth century. The Palace of afternoon crowd echoing through Camp Washington and the Fans (1902-1911) and Redland Field (1912-19 34), both the West End. Richard Miller, baseball historian, is a nationally recognized authority on old ballparks. Union Grounds was the home of baseball's first professional team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings. Queen City Heritage Union Grounds was the home of baseball's first professional team, the famous Cincinnati Red Stockings of i 8 69-1 8 70. Built in 1 8 67, it was located on the site of the fountain in front of where Union Terminal now stands, and served as the home of the Cincinnati Baseball Club from 1867 until 1870. The main wooden grandstand, called "The Grand Duchess," dominated the park. Rows of covered and uncovered bleacher seats ran part way out each foul line. The first time in Cincinnati fans paid admission fees to watch a baseball game was at Union Grounds. Silver coins were scarce and fans paid their way into the park with "shinplasters," ten, fifteen, twenty-five, and fifty cent paper currency. The paper currency was thrown into a barrel at the gate and took several hours to count. In 1869 the Red Stockings won all their home games and after defeating the best teams in the East were declared the national champions. from the professional ranks. Meat packers George and Josiah The team's winning streak ended midway through the 1870 Keck owned the club and they built the new park near their season when the Red Stockings lost to the Brooklyn Atlan- business. Located just north of the stockyards on Spring Grove Avenue, the park went by several names, including AMUSEBtENTg. the Cincinnati Baseball Park, Avenue Grounds, and BrighSTEW CIMCIJrJTATI BAHJbl-BAJLI, P A R K ton Park. Regular admission charge wasfiftycents, but there ONES M O R E were ten cent seats, after the fifth inning, and a special B j Special Bequest, Commencing THIS (MONDAY) AFTERNOON. section called the "Little Dukes" for those who wanted to be Owing to the continued success of near the bar. On September 6, 1877, Lipman Pike, the first Jewish player in the major leagues, and a favorite of Cincinnati fans, hit a Jim Devlin pitch for a home run over the right field fence that won the game 1 -o for Cincinnati over Louisville. This was the first time in major league history that a home run won a game 1 -o for a team. The next home of the Red Stockings, the Bank Street Grounds, was closer to downtown, at the corner of Bank Street and Western Avenue. There are no known photographs or illustrations of the park. The team moved here in 1880 to a vacant lot where the circus and wild west The management hare decided to remain another week. • shows played. This turned out to be the team's last year in Afternoon «,t 8 O'Olook.. the National League. Before the 1 8 81 season began, the /ADMISSION 15 AND SO CENTS. I CHILDREN IS CENTS. league expelled the club for selling beer and renting the park This places ttfe Century's Novelty within the reaoh of all. Street Cars right to the Rate. Doors open at 1 o'clock. for Sunday baseball. In 1881 amateur and semi-pro ball GRAND STREET PARADE THIS MORNING! teams used the park. In 1882 Cincinnati joined the American tics in extra innings. At the conclusion of the i 870 season, Association, the league of Sunday baseball, twenty-five cent the team disbanded, with many of the star players, including seats, and liquor in the park. The club must have enjoyed player-manager Harry Wright, moving to Boston. Wright these new conditions for they won the league, becoming also took his famous red socks and the Cincinnati nickname in 1882 Cincinnati's first league champions (there were no with him, and created the "Red Sox." leagues in 1 869). The first "World Series" occurred in October, The National League formed in 1876; Cincinnati rejoined the new league that year after a six year absence 1882 when the Reds, winners of the American Association The old ballparks hosted more than baseball games, as this 1884 advertisement indicates. The Reds were an American Association club until 1889 when they rejoined the National League. In 1884 the American Association Reds owners scrambled to find a new home—an old brickyard at the corner of Western Avenue and Findlay Street. Summer 1988 Cincinnati Ballparks 27 title, and the Chicago White Stockings (later the Chicago supporter of the rival Union League, called the park a death Cubs), winners of the National League, played at Bank trap, suggested children be kept away, and encouraged adults Street Grounds. The series ended in a tie of one game to check their life insurance policies before visiting the park. apiece. Other owners in the American Association pressured In fact, a portion of a grandstand walkway did collapse on Aaron Stern, a clothing merchant who owned the Reds, opening day and injured a few spectators. A sensational not to play a deciding third game and risk possible embar- story in the Enquirer erroneously reported that one person rassment to the Association should the Reds lose. was killed; this myth of an opening day fatality persists to In 1 884 the Reds failed to renew their park this day. lease on time. The enterprising upstart Union League beat Although the park was not a "death trap" for them to the punch and became the new tenants of the Bank fans, its layout killed a lot of hitter's hopes. Home plate faced Street Grounds. The American Association Reds scrambled the "wrong" way, to the west, so the afternoon sun was to find a new home and settled on an old brickyard at the directly in the batter's eyes. The only major league game ever corner of Western Avenue and Findlay Street. called because of the sun was cancelled in 1892 on a hot The Union League team had its problems at Sunday afternoon in a game against Boston. The batters had the Bank Street Grounds. The park's grandstand structure looked into the blinding rays of the sun which seemed to was weakened by floods and the outfield fence blew down perch majestically on top of Price Hill overlooking left field during the season. The club sold tickets on streetcars but for fourteen scoreless innings. attendance remained low and the new league and the park The Reds played at League Park as an Amerifaded away after the season ended. can Association club until 1889 when they rejoined the The American Association Reds opened a new National League. However, in 1 891, the American Associawooden park called League Park at the new site which tion returned briefly to Cincinnati with a new entry that writers referred to as the Western Avenue Orchard. An played its home games in the East End. This was the first ex-sideshow barker stood in front of the main entrance and time major league baseball invaded the eastern section of the hawked the pleasures of the game. The terrain sloped upwards city. The other four parks had been located along the Millcreek. in the outfield, and rather than leveling the field, manageThe home park for this short-lived American ment decided to use the terrace as a bleacher area. Baseballs Association venture was Pendleton Park, located near the of this era were spongy and "dead;" few balls were hit on a fly foot of Delta Avenue on the Ohio River. The hills of Kenas far as the terrace seats. tucky across the river, covered with beautiful green foliage, During the first season League Park was open, and the hard-working paddle wheelers chugging up and the home team had to compete for fans with Cincinnati's down the Ohio created a picturesque setting and atmoother team playing at the nearby Bank Street Grounds. The sphere like something out of Huckleberry Finn. newspapers took sides, and indicated their loyalties in their It was one of the few major league parks where descriptions of the new League Park. The Commercial Gazette,fans came to the game by steamboat. The steamer, Music, left firmly in the camp of the American Association Reds, called from the foot of Walnut Street every game day at 2:00 p.m. the new park the best in baseball, while the Enquirer, a sharp. The Pennsylvania Railroad ran just back of the main Queen City Heritage en ballpark during its lifetime, but few were as celebrated as the wedding at home plate. On September 18, 1893, the Reds defeated Baltimore and Louie Rapp, the Reds' assistant groundskeeper, married Rose Smith at plate. The bleachers were packed that afternoon and for the first time in the history of Cincinnati baseball, the fair sex had invaded the sun seats. A popular picture has been mistakenly identified as "Opening Day at Union Grounds, 1869." However, the photo is of League Park some ten years after it opened in 1884. The skyline beyond the grandstand which matches other photos taken from League Park is of Findlay Street, not of West End streets as would be the case if it were Union Grounds. Furthermore, the shape of the grandstand does not even closely resemble the sketch of Union Grounds. The flagpole and grandstand provide an addi- entrance, and many fans rode the train to the games. Streetcars which ran out Eastern Avenue were slow and crowded, and not a very convenient way to the ballpark. The characteristic that made the park romantic also proved to be its undoing. Its remote setting was just too far from downtown. Although transportation was readily available, it was slow and time consuming. The club remained in Cincinnati for about one half of the 1891 season before moving to Kansas City. The collapse of the American Association team, and the continued success of the Reds at League Park effectively sewed up the city for the National League. Baseball had found a permanent home in Cincinnati at the old brickyard at Western Avenue and Findlay Street, and the Reds played ball there until 1970. Many notable events occurred at the old wood- In the early years of baseball scorecards were very ornate, and they quickly became a part of the ballpark. Fans used them as megaphones, and to whack a neighbor on the head after a great play. This is a scorecard from the 1880's when the Reds played in old League Park. On the cover is a rare individual picture of Will White, who won forty games three times for the Reds. The decorated wagons and flags hint this is a festive occasion, such as an opening day. In the 1890's, the Reds regularly paraded in wagons to League Park through the streets of Over-the-Rhine to attract crowds. A fire in the middle of the 1900 season burned all of the main grandstand at League Park, sparing only the bleachers along the left field line. In order to give fans an acceptable view of the game-, the owners moved home plate in front of the remaining bleachers, which happened to be its original position when the park was first built. Batters again faced the sun. A roof was put over the old bleachers and these now served as the main grandstand for the makeshift ' a -<7 tional clue: touches of Queen Anne architecture which was not introduced into League Park until 1894 when club owners moved home plate so that batters faced east instead of west. They built a new grandstand behind the new home plate area and it featured these architectural details. This view of the Findlay Street skyline was only possible after the field was turned. Located on the Ohio River, Pendleton Park offered a panoramic view of the hills of Kentucky. After professional baseball was no longer played here, the Cincinnati Gymnasium and Athletic Club added a swimming pool and club house to the grounds. Mistakenly labeled "Opening Day 1869," this picture is League Park in the 1890's— approximately ten years after it opened. On September 18, 1893, Louie Rapp, assistant groundskeeper for the Reds, married Rose Smith at home plate. Queen City Heritage park in which the Reds played the second half of the 1900 season and all of the 1901 season. League Park was the most difficult one in baseball to play third base. Rays of the sun reflected off the skin infield. Worse, the third baseman had to pick up the rapidly moving ball against a sea of white. The white letters of the big sign on the front of the temporary wooden bleachers and a shirt-sleeved crowd in the bleachers gave him an almost all white background. On big game days, when the park would not hold the crowd, fans found box cars, sitting on the railroad tracks back of left and centerfieldexcellent—and cheap—seats. Reds' owner, John T. Brush, an Indianapolis merchant, had an elaborate new grandstand constructed to replace the one lost in the fire. In 1902, the Reds opened the new stands and renamed League Park, "The Palace of the Fans." That summer, Brush sold the club to local interests, including businessmen Julius and Max Fleischmann, and political bosses George B. Cox and August "Garry" Herrmann. Herrmann became president of the club, and remained in The Palace of the Fans was the first major league baseball park with definite architectural overtones, and the second to use iron and cement. (Photo courtesy Tom Pfirrman, Baseball Card Corner) control until 1927. Befitting a new century and baseball's growing role in American society, the new grandstand featured a distinctive architectural design, patterned after the motif of the Chicago World's Fair. The Palace of the Fans was the first major league baseball park with definite architectural overtones, and it was the second to use iron and cement as the major part of its foundation and superstructure. The first park built primarily of other material other than wood was the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, home of the Phillies. Only the main grandstand of the Palace of the Fans was cement and sculptured iron. The right field pavilions and bleachers were wood. These sections survived the 1900 fire and were incorporated into the new park. The completion of the new grandstand enabled the team to move home plate back to its "proper" location so that batters faced east instead of west. The Palace of the Fans was long on looks but short on seats. It had the lowest number of box seats in the major leagues, and as a result, the lowest per capita income in the league. After the 1911 season, the new grandstand and the old wooden bleachers were razed, and owner Herrmann contracted with Cincinnati architects Hake and Hake to construct a new park with more box seats. The result was Redland Field, a spacious park with one of the largest playing areas in the major leagues. Centerfieldwas 420 feet from home plate and it was 3 60 feet down both lines. The dimensions indicate the conservative philosophy of the owners toward offense and the dominance of defense. It was 1921 before Cincinnati outfielder Pat Duncan hit the first home run over the fence at Redland Field. Duncan's homer cleared the left field wall and hit a surprised policeman standing on York Street. Thefirstplayer The new Palace of the Fans grandstand featured a distinctive architectural design patterned after the motif of the Chicago World's Fair. Summer 1988 Cincinnati Ballparks ever to hit a ball over the center field and right field fences at Redland Field, did so in an exhibition game later in the 1921 season. His name: Babe Ruth. The only World Series played at Redland Field was in 1919 between the Reds and the Chicago White Sox. Redland Field took on a new look for the Series with temporary stands built over York Street. These seats provided the only left field bleachers the park ever had and sold for S 3.00. The Reds won the Series but the victory was tainted when several White Sox players admitted that they conspired with gamblers to throw the games. Many sports writers failed to sense something was wrong and felt the Reds had fairly won a hard-fought series, which they did. Most of the players involved in the THE NEW BALL PARK, BEDLANO FIELD, CINCINNATI, OHIO. After the 1911 season August Herrmann commissioned Cincinnati architects Hake and Hake to design a new park with more box seats. The result was Redland Field, a spacious park with the largest playing area in the major leagues. Queen City Heritage £CTRIC CO. • DYHAMOS * SALJ c UMMf&S II I PUWI M « i48 R.UNE 9 LUKE 7 WITH- scandal played as hard as they could after a promised payoff never materialized. Beyond the fence and the Scoreboard, which was designed by park superintendent Matty Schwab especially for the series, the "Western Avenue irregulars" jammed windows and building tops, and even climbed telephone poles for a view of the action. These fans painted a vivid portrait of the "renegade" bleachers and the neighborhood environment that was so much a part of the character of the old Cincinnati ballparks. Park superintendent Matty Schwab was more than just an employee of the ballpark. He was the ballpark. Matty was groundskeeper at the Cincinnati parks for sixtynine years and park superintendent for sixty years. In his tenure he saw twenty-six full time managers and over i ,000 different players come and go for the Reds. Matty readied the park for four World Series, and cleaned up after several floods. He saw one park burn and four different parks built, all on the same site, the corner of Western Avenue and Findlay Street. The terrace in right and center field at old Crosley Field was designed by Matty. He designed the bases used in every major league park, and designed the drainage The "Western Avenue irregulars" jammed windows and building tops to view the 1919 World Series. system in Cincinnati and many other parks. He worked with hundreds of umpires and six owners and won praises from all of them. He built the scoreboards in Redland Field and Crosley Field. Schwab owned his own Scoreboard company and built the Scoreboard in the Polo Grounds in 191 3, and the one in Ebbets Field a short time later. Subsequently In this picture, the Reds' first baseman Jake Daubert has just made the first hit of the 1919 series. Four of the eight "Black Sox" players who were barred from baseball for life because of their involvement in the scandal are in the field: third baseman Buck Weaver, shortstop Swede Risberg, pitcher Ed Cicotte, and left fielder "Shoeless" Joe Jackson. Cincinnati Ballparks he erected scoreboards in Toronto, Boston, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Yankee Stadium, and other parks. Matty Schwab's father, John, was groundskeeper at old League Park in the late i 88o's. He held this position until Matty succeeded him in 1903. Matty's son, Matthew, was park superintendent in Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds, and Candlestick Park. His grandson, Mike, succeeded Matty as superintendent at Crosley Field after he retired in 1963. Usually club owners hire general managers to run their teams. But in 1934, the Reds went about it backwards: general manager Larry McPhail, one of the best in the business, persuaded Powel Crosley, Jr. to purchase the Reds. It was a wise choice. Crosley had the image, money, and business experience to head a successful major league franchise, especially in a time of general economic depression. Crosley had personally broadcast the first Cincinnati baseball game ever heard on radio, and had been absorbed by the game as a youngster. As owner of the Reds, Crosley again grew to love the game that he had drifted away from over the years. He became one of the game's great innovators, hosting professional baseball's first night game in 1935, and promoting baseball on radio. Crosley, a successful businessman, generally avoided promoting his products directly at the ballpark. The only time he ever associated business and baseball was in the mid-1930's immediately after he purchased the club. Repli- Matty Schwab worked at the Cincinnati parks for sixty-nine years and held the title of park superintendent for sixty years. 33 cas of Crosley products, a washing machine and a radio, appeared at the top of the Scoreboard on either side of the clock for a couple of seasons. Powel Crosley, Jr. had the honor of being in the best of company of other owners who have had major league parks named for them: Ebbets, Shibe, Wrigley, and Comiskey. Major league night baseball was a product of the Great Depression. As the nation's economic malaise lingered, attendance suffered at the parks in both the National League and American League. One solution advocated by many was night baseball; high school football and minor league baseball had played games under the lights for years. During the 19 34 winter meetings, the National League voted to allow seven night games for each team in the 1935 season. Only Powel Crosley, Jr. and Larry McPhail grabbed the opportunity. The other owners, a genuinely conservative lot, feared that fans would not be able to see as well and that clubs would be swamped with requests for refunds. But Crosley and McPhail, saddled with a last place club and thousands of empty seats, figured they had little to lose. The first night game was held May 23, 1935, and by long distance, President Franklin D. Roosevelt switched 632 lights on. The Reds beat the Phillies 2-1. A crowd of 20,422 watched, about ten times the number for a regular weekday game, and nobody asked for their money back. Except for the Giants who refused to play night baseball, the Reds played one night game with every team in In 1934 Powel Crosley, Jr. purchased the Reds and became one of the game's great innovators. Powel Crosley, Jr. (center) with Manager Bill McKechnie (on left) and General Manager Warren Giles (on right). Queen City Heritage ", the league that season. Night baseball was born out of financial necessity, and its success was immediately measured in gate receipts. In 1935 the total attendance for seven night games in Cincinnati was 1 30,3 37—a figure that exceeded the total home attendance in seventy-seven games for some teams that year. On the night of July 31, 193 5, a most bizarre event took place. The St. Louis Cardinals were in town. The Night baseball proved a success for the Cincinnati franchise. Over 130,337 fans attended the seven night games in 1935. Cards were a flamboyant bunch, the old rough and tumble Gas House Gang: the Dean brothers, Frankie Frisch, Pepper Martin, Leo Durocher, Joe Medwick, and many other colorful characters. Fresh off a world championship they were a big draw in any town. Combined with the novelty of a night game, the Reds enjoyed a big advance sale, but an even bigger crowd showed up for the game. The general admission pavilion seats down Summer 1988 Cincinnati Ballparks The Cincinnati Post r. VOL. 110. i >»O. 38, H \\ 1 ' 1N« I.W.Vri. • n i l l M U Y , .AUGUST 3, 1935,. Part of 30,000 Crowd That Kicked Up Heels at Night Game tti Or«sle* fielA at test nirbt** e td«ng the the foul line were quickly filled. Late arrivals poured over into the empty reserved grandstand seats and filled those as well. An excursion train loaded with fans from Dayton, Ohio, arrived just before game time and found their reserved seats already occupied. The excursion leader promptly marched the group onto the field and stood them along the right field foul line. Other spectators kept arriving and soon the outfield was lined with fans from foul line to foul line. As the game progressed the crowd inched up the sidelines until people stood five and six deep along the lines and back of home plate making it impossible for a player to move through the crowd to catch a foul fly. Players from both teams left their dugouts for a better view of the game. Relief pitchers had to warm up between the crowd and the dugouts, and some spectators were so close to the The Cincinnati Post gave front page coverage to the near riot crowd conditions at the July 3 1 , 1935, night game. feasr me plate. (Photo by Carl B»wrs, Post staff cameraman). bullpen catcher that they flinched each time the pitch smacked into the catcher's glove. The carnival atmosphere reached a peak when Kitty Burke, one of the spectators on the field, commandeered a bat from Red's slugger Babe Herman and strode up to the plate between innings. She stood in the batter's box with the bat on her shoulder while the Cardinal pitcher warmed up. Official attendance figures tallied 3 0,001 fans, but Larry McPhail said many more had jumped over the turnstiles on their way into the park. Even without the turnstile vaulters, this was a serious overflow crowd. The pavilions had not yet been double-decked, so the park officially only held about 26,000. The mind boggling fact of the evening was that the Commissioner of Baseball, Judge K.M. Landis, and Queen City Heritage Reds' owner Powel Crosley were in attendance. Neither ordered the game stopped despite the obvious threat of injury to a fan, nor did the St. Louis manager ask for a forfeit due to the unusual playing conditions. Following the game a new head usher was named and Matty Schwab suggested that the left field terrace be extended to center and right fields for the seating of the overflow crowds in the outfield (a common practice at the time). The terrace was completed before the end of the season. In later years, when fans were no longer permitted to sit on the field, the terrace served as a warning "track" for outfielders. The 1937 Flood, one of the most devastating in Cincinnati history engulfed Crosley Field. Flood waters reached twenty-one feet at home plate and completely covered the left and center field walls. Lee Grissom, the Reds' eccentric left hander, and John McDonald, the club's traveling secretary, happened to be meeting in McDonald's downtown office at the time of the flood. Grissom, who had already borrowed The 1937 Flood engulfed Crosley Field with flood waters completely covering the center and left field walls. against his 1937 salary, was requesting another $50 advance from the club, when word reached McDonald that the flood waters were now precariously close to reaching the team records housed at the ballpark. McDonald said no to Grissom's request, but asked him to come along to the ballpark to rescue the records. The only way into the park was by boat, and as the two rowed over the left center field fence, Grissom asked McDonald if he could swim. McDonald said no. Grissom replied, "Well, you had better learn, because you are going over if I don't get the $50." No monument marks the site of this incident, but a yellow line on the Scoreboard and a yellow ring around theflagpolemarked the high tide of the 1937 flood water in the outfield area of Crosley Field. Night baseball and other innovations aside, the Reds still felt the impact of the Depression. General admission tickets in 1937 cost $ 1 and bleacher seats were sixty cents but often the only sizeable block of fans in attendance at games was from Cincinnati's Knothole Club, begun in Summer 1988 Cincinnati Ballparks 1934 with the backing of Larry McPhail. The club played a big part in the personality of Crosley Field. Every day except Ladies Day, Sundays, and holidays was Knothole Day. Youngsters ages nine to sixteen could join, and each member received a special colored card. A radio program for Knotholers told, among other things, what colored cards were good for admission on what days. The regular Knothole section was in the right field pavilion, but sometimes the left field pavilion was open as well. The two sections would compete to see which one could root the loudest. After 1938 the Knotholers sat in the upper deck of the pavilions and stomped their feet on the metal floor until the noise reached a deafening crescendo. The teams played more and more night games after World War II, and as a result, Knothole days became fewer and fewer. The familiar tenor cadence of young fans, unprompted by Scoreboard machinations, shouting "We want a hit, we want a hit!" gradually faded into the past and was lost forever. In the 19 3 o's and 1940's radio became a familiar part of Cincinnati baseball and Dick Bray, along with well-known broadcasters Red Barber and Waite Hoyt, became a part of the history of Crosley Field. Bray did a fifteen minute radio program, "Fans in the Stands," before each home game. It was a light-hearted, fast-paced program that gave the fans at home a sense of being at the park. Bray borrowed the idea from the old Olson and Johnson comedy team whom he had heard interview fans before the 19 34 World Series. When he came to Cincin- nati's WSAI in 19 3 7 as Red Barber's assistant, Bray suggested interviewing people standing in line for opening day tickets. Powel Crosley, Jr. heard the program, called the station manager, and said he wanted the show done the next day from the bleachers. This was the start of a seventeen-year marriage between Dick Bray and the fans in the stands at Crosley Field. He carried a thirty-two pound transmitter on his back for each broadcast and interviewed more than 35,000 fans. Each person who appeared on the program received a coupon for a loaf of Rubels Rye Bread. The Reds had participated in only one World Series (1919) in the thirty-six years of the event until 1939 when the team returned to the fall classic. The Reds' long wait for a place in the sun was quickly eclipsed by four straight losses to the Yankees, topped off by Ernie Lombardi's famous "snooze" at home plate. The Reds' Hall of Fame catcher was momentarily knocked out by a knee to the groin by Yankee runner Charlie Keller; by the time Lombardi recovered, Joe DiMaggio had scored a second run. 17 The next season, the Reds' repeated as National League champs and were back in the series against the Detroit Tigers. The deciding seventh game was played at Crosley Field. The Reds were down 1 -o in the seventh when they scored twice to take the lead. Paul Derringer held the Tiger's scoreless over the last two innings, and the Reds had won their second World Series, this one untainted by scan- The Great Depression had an economic impact on the Reds and often the only sizeable group attending was from the Cincinnati Knothole Club. Dick Bray did a fifteen minute program, "Fans in the Stands" for seventeen years. Sometimes Bray interviewed celebrities such as baseball commissioner A. B. "Happy" Chandler. 38 dal. It was also the only World Series the Reds have ever clinched at home. Interestingly, the game was not a sellout. By 1961, Crosley Field had ceased to be a neighborhood park. The automobile in post-World War II Cincinnati changed forever the urban landscape surrounding Crosley Field. The ballpark was no longer a part of the neighborhood; there was no neighborhood left to be a part of. Even though Crosley Field remained the same, the third generation of ballparks had arrived: the ballpark as spectacle, a bigger than life object that dominated its surroundings. From this time on, no new park could be built without bowing to the automobile; acres of adjacent parking and freeway access dictated the location and design of new stadiums in Cincinnati and other cities. The era of the neighborhood park was gone. In the final game of the 1940 World Series at Crosley Field, Jimmy Ripple tagged up and scored the winning run on a long fly to center field by Billy Myers. Queen City Heritage The razing of the neighborhood for additional parking marked the end of Crosley Field as a neighborhood park, but the timing was right for the Reds. A team that was picked to finish fifth or sixth quickly moved into contention and drew big crowds all year. The Reds wound up in the World Series on the strength of believing in themselves, on the great pitching of Joey Jay, Jim O'Toole, and Bob Purkey, on a solid outfield featuring the league's Most Valuable Player, Frank Robinson, and on the inspiration of manager Fred Hutchinson. The ragamuffins of 1961 proved to be just that, however, in the Series. The Reds split the first two games at Yankee Stadium, but then lost three straight at home. The final game on October 9,1961 was the last World Series game played at Crosley Field. Cincinnati Ballparks Summer 1988 • tiardi, Wil The World Champion Reds rushed onto the field to congratulate Paul Derringer, winning pitcher of the final game. Queen City Heritage 4o In addition to the World Series games of 19 3 9, 1940, and 1961, and the first night game in 1935, Crosley Field was the scene of many other notable events. These included: * The 1938 and 1953 All-Star games * Walker Cooper's ten RBPs in one game in 1949 * Frank Robinson's hitting for the cycle (home run, triple, double, and single in one game) in 1959 Art Shamsky's four consecutive home runs (in two games) in 1966 *Jim Maloney striking out eighteen batters in one game in * 11965 * Back-to-back no hit games by Maloney and Houston's Don Wilson in 1969 *No hitters by Clyde Shoun (1944), Ewell Blackwell (1947), and Maloney (1965 and 1969.) Reds pitcher, Johnny Vander Meer pitched consecutive nohit games in 1938. The first came against the Boston Braves at Crosley Field; the final out is pictured here. The second no hitter came four days later in the first night game played at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field. This view of the left field area of Crosley Field about 1940 vividly portrays the park as part of the urban fabric. Advertising signs and landmarks immediately beyond the fence were extensions of the park itself. Summer 1988 In 1938 the first half of perhaps the greatest pitching feat in modern baseball, the consecutive no-hit games of Reds pitcher Johnny Vander Meer, was accomplished at Crosley Field. Four days later, in the first night game played at Brooklyn's Ebbets Field, Vander Meer again pitched a no-hitter, beating the Dodgers 6-0. He was thereafter known as "Double No-Hit" Vander Meer, and his performance has never been equalled. The pitcher to come the closest was another Red, Ewell Blackwell, and ironically, the same clubs were again involved. Blackwell pitched a no-hit game against the Boston Braves on June 18,1947, and in his next start against Brooklyn, he threw no-hit ball into the ninth inning before finally giving up a single. By the mid-i 960's, it was clear that the Reds needed a new ballpark if the team was to remain in Cincinnati. In an era when franchise shifts were common, the city made a commitment to do what was necessary to keep the Reds from moving. Riverfront Stadium became a reality as downtown development needs, parking considerations, freeway access, and the participation of the Cincinnati Bengals came together. From the beginning, Riverfront was designated as a modern, multi-purpose, bowl-shaped stadium. Construction began in 1968; the final game at Crosley Field was played on June 24, 1970. A 100 year tradition of professional baseball in the Mill Creek valley had ended. Crosley Field's home plate was saved and installed in Riverfront, and the first game in the new stadium was played June 30, 1970. Cincinnati's era of modern ballparks had officially begun. The decline of public transportation and the popularity of the automobile caused major problems for Crosley Field and the Cincinnati baseball team. : • • • 1. Much of the information in this article is taken from research by Richard Miller for his forthcoming book on the nation's oldest baseball parks. All photographs and other memorabilia are courtesy of the Richard Miller Collection, Archives and Rare Books Department, University of Cincinnati Libraries and the Cincinnati Historical Society. Crosley Field served as an auto yard before it was razed in 1972.

© Copyright 2026