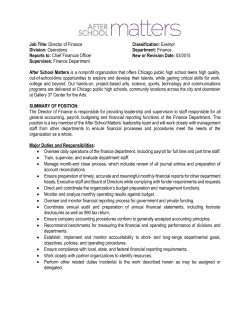

Issue - The University of Chicago Magazine