Clinical Communications: Adults

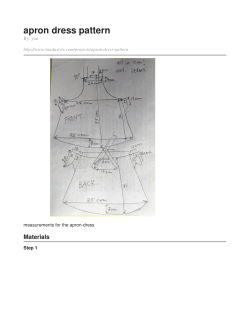

The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. -, No. -, pp. 1–4, 2011 Copyright Ó 2011 Elsevier Inc. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0736-4679/$ - see front matter doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.052 Clinical Communications: Adults PHENYTOIN-INDUCED DRUG REACTION WITH EOSINOPHILIA AND SYSTEMIC SYMPTOMS (DRESS) SYNDROME: A CASE REPORT FROM THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT Lindsay L. Oelze, MD* and M. Tyson Pillow, MD*† *Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas and †Department of Medicine, Section of Emergency Medicine, Ben Taub General Hospital, Houston, Texas Reprint Address: Lindsay L. Oelze, MD, Department of Medicine, Section of Emergency Medicine, Ben Taub General Hospital, 1504 Taub Loop, EM Academic Offices, Houston, TX 77030 , Abstract—Background: Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is an uncommon but serious hypersensitivity drug reaction most frequently associated with antiepileptics. Clinical manifestations include rash, fever, and visceral organ involvement, most commonly hepatitis. The mortality rate associated with DRESS syndrome is approximately 10%, the majority due to fulminant liver failure. Objectives: We report one case of phenytoin-induced DRESS syndrome in a patient who presented to the Emergency Department (ED). Our objectives for this case report include: 1) to learn the importance of DRESS syndrome; 2) to recognize the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome; 3) to know what diagnostic studies are indicated; and 4) to learn the appropriate treatment. Case Report: We report one case of phenytoininduced DRESS syndrome in a 34-year-old man, previously on phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis, who presented to the ED with 5 days of worsening symptoms including generalized rash, fever, tongue swelling, and dysphagia. Laboratory results revealed an eosinophilia and elevated liver enzymes. With initiation of steroids, the transaminitis improved despite increasing eosinophilia and development of an atypical lymphocytosis. Fever and angioedema resolved with improvement of the rash, and the patient was discharged on hospital day 3. Conclusion: Given the significant mortality related to DRESS syndrome, ED staff should have a low threshold for suspecting the condition in patients who present with unusual complaints and skin findings after starting any antiepileptic drug. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with corticosteroids is imperative. Elsevier Inc. Ó 2011 , Keywords—DRESS syndrome; phenytoin; drug reaction; hypersensitivity reaction; antiepileptic-induced hypersensitivity reaction INTRODUCTION Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was first described in 1959 associated with phenytoin and was previously referred to as drug-induced pseudolymphoma (1). It is characterized by skin rash, fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, and visceral organ involvement, typically presenting within 8 weeks of initiation of therapy. This reaction can be life threatening, with a mortality rate of approximately 10%, most commonly secondary to liver failure (2). The exact incidence of DRESS syndrome is unknown, but it is estimated to occur in at least 1 per 1500 new users of phenytoin and carbamazepine (3). A majority of reported cases are African-American males (2). Typically, fever precedes the development of a diffuse, morbilliform rash that can advance to an exfoliative dermatitis. According to a recent observational study of 24 patients with DRESS syndrome, all presented with rash and fever, RECEIVED: 4 October 2010; FINAL SUBMISSION RECEIVED: 15 November 2010; ACCEPTED: 23 May 2011 1 2 L. L. Oelze and M. T. Pillow 50% with abnormalities on complete blood count (CBC) including eosinophilia (> 500/uL) or presence of atypical lymphocytes, > 90% with hepatitis, 60% with localized or generalized edema, 33% with lymphadenopathy, and 30% with pharyngitis (4). Other organs can be involved leading to interstitial nephritis, myocarditis, pneumonitis, and rarely, meningoencephalitis (2). When a patient presents to the Emergency Department (ED) with skin findings and unusual complaints after starting any new drug, particularly antiepileptics, physical examination and appropriate diagnostic testing should be performed to detect systemic involvement. Initial testing should include a CBC with differential and peripheral smear, liver panel, serum creatinine, chest X-ray, and urinalysis. CASE REPORT A 34-year-old African-American man presented to the ED complaining of a 5-day history of generalized pruritic, morbilliform rash associated with fever to 39.4 C (103 F), tongue swelling, and dysphagia. He had undergone craniotomy 16 days prior to presentation for resection of an anaplastic astrocytoma at an outside facility. The patient had been loaded with fosphenytoin at the time of surgery and transitioned to oral phenytoin. He had been on phenytoin for just over 2 weeks when symptoms began. Three days before arrival in the ED, he had been seen at an outside hospital for the same complaints and phenytoin was replaced with levetiracetam. The symptoms worsened despite discontinuation of phenytoin prompting the patient to again seek care in the ED. Medications at the time of presentation included levetiracetam 2000 mg orally (p.o.) twice a day (b.i.d.), dexamethasone 4 mg p.o. b.i.d. (since craniotomy), lisinopril 5 mg p.o. daily, and acetaminophen. Review of systems was negative for cough, prior rash, joint pain, or any other contributing symptoms. He denied any known drug allergies, other past medical history, and alcohol use. He did have a 10 pack-year smoking history. On examination, the patient was febrile to 38.7 C (101.6 F), with a pulse of 96 beats/min and a blood pressure of 120/59 mm Hg. The patient was alert and fully oriented, appearing uncomfortable, but non-toxic. A diffuse, blanching erythema was noted involving the face, trunk, and extremities without desquamation (Figures 1–3). There was no involvement of the oral mucosa, palms, or soles. Nikolsky test was negative. There was angioedema of the lips and tongue without airway compromise. No erythema or exudate was noted upon examination of the posterior pharynx. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated, and breath sounds were clear to auscultation bilaterally with a regular rate and rhythm on cardiovascular examination. There was no organomegaly or abdominal tenderness. Neurologic examination was non-focal, with no deficits noted. Figure 1. Diffuse erythematous rash on the arm of a patient who presented with DRESS syndrome. Laboratory results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 9.8 with 81% neutrophils and 7% eosinophils or 0.69 K/uL abs eosinophils (normal 0–3%). The patient also was noted to have a transaminitis with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 131 U/L (normal 30–65 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 387 U/L (normal 15–37 U/L), and alkaline phosphatase of 198 U/L (normal 50–136). A phenytoin level was 5.4 (therapeutic 10–20) and basic Figure 2. Diffuse erythematous rash on the leg of a patient who presented with DRESS syndrome. DRESS Syndrome 3 Figure 3. Diffuse erythematous rash on the back of a patient who presented with DRESS syndrome. metabolic panel was unremarkable. A hepatitis panel and abdominal ultrasound were negative. A chest X-ray revealed mild perihilar prominence with peribronchial thickening. The patient was admitted with a diagnosis of DRESS syndrome. Dexamethasone was increased to 4 mg p.o. four times a day and levetiracetam was continued at the same dose and frequency. On hospital day 1, transaminases worsened, with ALT of 602, AST of 211, and alkaline phosphatase of 245. Repeat CBC showed improvement in the eosinophilia to 3%, but an atypical lymphocytosis of 10% with white blood cell (WBC) count of 11.8. Lisinopril was discontinued due to possibility of contribution to the angioedema. On hospital day 2, the transaminitis showed improvement, but CBC demonstrated an increase in atypical lymphocytes to 31%, in addition to an absolute eosinophil count of 0.7 K/uL with 3% eosinophils on differential. All symptomatology was resolving. On hospital day 3, the transaminases had continued to improve to 475 and 84 for ALT and AST, respectively. An increased atypical lymphocytosis was noted to 45% on differential, with a WBC count of 34. Absolute eosinophils increased to 2.39 with 7% eosinophils. Because the patient’s symptoms had continued to improve with resolution of fever and angioedema, he was discharged home on hospital day 3 on continued dexamethasone and levetiracetam with close follow-up with Oncology. DISCUSSION Although most commonly associated with phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital, DRESS syndrome has also been reported after exposure to a myriad of medications including lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, vancomycin, sulfasalazine, doxycycline, allopurinol, linezolid, nitrofurantoin, atorvastatin, and esomeprazole (2,5–12). Interestingly, the first case of DRESS syndrome related to levetiracetam was described just last year (13). Most cases of DRESS syndrome occur within 8 weeks of exposure, but one case report occurred 4 months after initiation of carbamazepine (14). Although formal diagnostic guidelines have not been formed, Bocquet et al. proposed the following three absolute criteria for diagnosis: 1) cutaneous drug eruption, 2) eosinophilia > 1.5 109/L or presence of atypical lymphocytes, and 3) systemic involvement indicated by adenopathies > 2 cm in diameter, hepatitis, interstitial nephritis, interstitial pneumonitis, or carditis (2). More recently, a Japanese consensus group established a revised set of diagnostic criteria requiring all seven of the following: 1) maculopapular rash developing > 3 weeks after starting a limited number of drugs, 2) prolonged clinical symptoms 2 weeks after discontinuation of the causative drug, 3) fever, 4) liver abnormalities (ALT > 100), 5) leukocyte abnormalities (leukocytosis > 11 109/L , atypical lymphocytes > 5%, or eosinophilia > 1.5 109/L), 6) lymphadenopathy, and 7) human herpes virus 6 reactivation (15). The last criteria refers to more recent but controversial evidence that DRESS syndrome may be caused by a reactivation of or new infection with human herpes virus 6 (15). CONCLUSION When DRESS syndrome is in the differential diagnosis, one should also consider other dangerous causes of severe cutaneous drug reaction such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. These typically occur sooner after drug exposure than does DRESS syndrome, within 1–3 weeks. The systemic symptoms and eosinophilia are also useful distinguishing characteristics, as is the absence of Nikolsky sign with DRESS syndrome. Other serious causes of a diffuse rash with signs of systemic involvement include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and, in the pediatric population, Kawasaki disease. Benign etiologies in the differential include mononucleosis with viral exanthem and simple drug reaction. When a patient presents to the ED with signs and symptoms concerning for a hypersensitivity reaction, a thorough drug history should be obtained, including drugs started up to 6 months before presentation. A careful examination should be performed looking for lymphadenopathy, edema, and hepatomegaly. Initial laboratory evaluation should include a comprehensive metabolic panel with liver enzymes, complete blood count with differential and peripheral smear, chest X-ray, and urinalysis. The liver enzymes should be followed for improvement, as the most common cause of mortality in patients with DRESS syndrome is hepatic failure (2). Although there are no published admission criteria, patients with DRESS syndrome should be admitted if 4 L. L. Oelze and M. T. Pillow there is concern for worsening liver enzymes, or if there are other laboratory abnormalities indicative of systemic involvement that need to be trended, such as an elevated creatinine with concern for acute renal failure secondary to interstitial nephritis. Certain abnormal findings on physical examination would also warrant admission and close observation, such as angioedema or altered mental status. The mainstay of treatment consists of corticosteroids, often producing rapid improvement in symptomatology (5). Supportive therapy includes antipyretics, antihistamines, topical steroids, and topical moisturizers. Relapse is possible with repeat exposure to the offending drug and when steroids are tapered or discontinued (5). Family members of the patient should be counseled as DRESS syndrome has been described in familial aggregations (2). In conclusion, DRESS syndrome is a severe hypersensitivity reaction that has been implicated with numerous drugs. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with corticosteroids is imperative. Emergency physicians should consider DRESS syndrome when evaluating patients who present with skin rash and unusual or systemic complaints in association with any new medication, particularly antiepileptics. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. REFERENCES 1. Saltzstein S, Ackerman L. Lymphadenopathy induced by anticonvulsant drugs mimicking clinically and pathologically malignant lymphomas. Cancer 1959;12:164–82. 2. Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia 14. 15. and Systemic Symptoms: DRESS). Semin Cutan Med Surg 1996; 15:250–7. Tennis P, Stem RS. Risk of serious cutaneous disorders after initiation of use of phenytoin, carbamazepine, or sodium valproate: a record linkage study. Neurology 1997;49:542–6. Ben m’rad M, Leclerc-Mercier S, Blanche P, et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: clinical and biological disease patterns in 24 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:131–40. Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology 2003;206:353–6. D’Orazio JL. Oxcarbazepine-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46: 1093–4. Vauthey L, Uckay I, Abrassart S, et al. Vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome in a female patient. Pharmacology 2008;82: 138–41. Mailhol C, Tremeau-Martinage C, Paul C, et al. Severe drug hypersensitivity reaction (DRESS syndrome) to doxycycline. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2010;137:40–3. Savard S, Desmeules S, Riopel J, et al. Linezolid-associated acute interstitial nephritis and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:e17–20. Velema MS, Voerman HJ. DRESS syndrome caused by nitrofurantoin. Neth J Med 2009;67:147–9. Gressier L, Pruvost-Balland C, Dubertret L, et al. Atorvastatininduced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009;136:50–3. Caboni S, Gunera-Saad N, Ktiouet-Abassi S, et al. Esomeprazoleinduced DRESS syndrome. Studies of cross-reactivity among proton pump inhibitors. Allergy 2007;62:1342–3. Lens S, Crespo G, Carrion JA, et al. Severe acute hepatitis in the dress syndrome: Report of two cases. Ann Hepatol 2010;9:198–201. Seth D, Kamat Deepak, Montejo J. DRESS syndrome: a practical approach for primary care practitioners. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008; 47:947. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. Br J Dermatol 2007;156: 1045–92.

© Copyright 2026