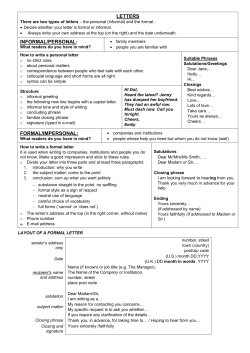

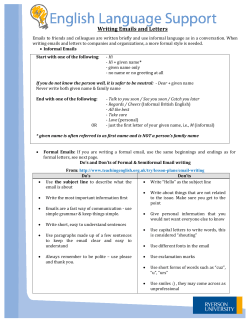

Latest draft