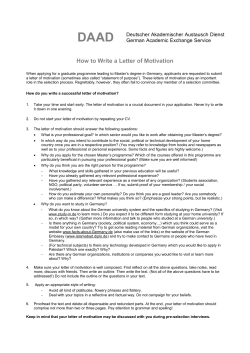

European History Dead People Who Pissed Off Other