15 CS2 L10 Handout USA 1920

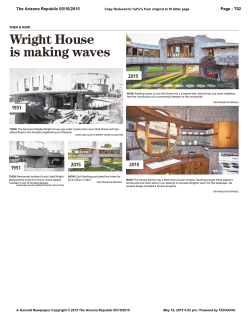

1 Modern Architecture in the USA – Immigration and Assimilation 1920–1960 CS2 12 May 2015 Christoph Schnoor/Graeme McConchie In this lecture a number of architects are presented who fostered the dissemination of modern architecture in the USA, between 1920 and 1960. A number of European architects fostered the dissemination of modern architecture in the USA between 1920 and 1960. Many of these had emigrated at the outbreaks of the two World Wars, around 1914 and 1939. Rudolph Schindler arrived in 1914, and Richard Neutra in 1923 – both from Austria. Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe left a politically hostile Germany in 1933 and 1937 respectively. Eero Saarinen (Finland) and Louis Kahn (Estonia) had emigrated somewhat earlier as youngsters. Also included are eminent visitors Alvar Aalto (Finland) and Le Corbusier (Swiss/French). These architects are presented alongside/in contrast to American architects Frank Lloyd Wright and Philip Johnson, who – in very different ways – strongly shaped the appearance of modern architecture in the USA. Richard Neutra (1892–1970) Austria Worked with Adolf Loos in Vienna (1912-14) and Erich Mendelsohn in Berlin (1921-23). In 1923 he emigrated to the USA, working first with Holabird and Roche in Chicago. Neutra met Sullivan and Wright and in 1925 he set up in partnership with Rudolf Schindler in Los Angeles. Together they built the Jardinette Apartments (1927), using reinforced concrete, cantilevered balconies, and horizontal strips of metal-framed windows. It was one of the first International Modernist buildings in America. Neutra and Schindler collaborated on a project for the League of Nations competition in Geneva (1926-7); but their partnership fell apart when Neutra accepted a commission by Philip Lovell to build his Health House which “served as both a residence for his politically committed physician and hygienist and [as] a nursery school”. (Cohen, 231) The Lovell Health House (1927–1929) was “the first American domestic structure to utilize a steel frame” (Cohen, 231), largely made of components selected from catalogues. Neutra became a visiting critic at the Bauhaus. His most productive years as an architect were the 1930s and 1940s when he designed several houses for famous Hollywood names (e.g. the Josef von Sternberg House, 1936). The Kaufmann House, Palm Springs, California (1946–47), was influenced by Mies van der Rohe’s designs. “Neutra studied at the Technische Hochschule in Vienna (1911–1918), incorporating into his work the influence of Adolf Loos and Frank Lloyd Wright. […] From 1921 until 1923 he worked for Erich Mendelsohn; moving then to USA, he worked in Chicago for Holabird and Roche and for Frank Lloyd Wright in Taliesin, Wisconsin. In 1925 he set up in partnership with Rudolph Schindler in Los Angeles, and they collaborated on several projects. Neutra’s early work in California included the steel-framed Lovell Health House (1927–1929); the Josef von Sternberg House (1936) and the large-scale Channel Heights housing Project in San Pedro (1942–44). His most famous houses, regionalized versions of the International Style, are his Kaufmann Desert House (1946–47), at Palm Springs, and the Tremaine House in Santa Barbara (1947–48).”1 Rudolf Schindler (1887–1953) Austria Schindler emigrated from Austria in 1914, having studied under Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and having worked with several Viennese modern architects. Attracted by Frank Lloyd Wright’s publication of the Wasmuth Volumes (1910), he came to Chicago to work for Wright. He went to Los Angeles 1 Hasan-Uddin Khan: International Style (Cologne: Taschen, 1998), 231. 2 in 1921, where he built the Schindler/Chase House for himself and his wife and another married couple. It is influenced by Wright, but it is stronger in its attempt to simplify. Curtis sees it as a “miniature essay on the theme of the origins of dwelling.”2 In his Lovell Beach House W. Curtis finds there were “obviously lingering debts to Wright, but the house was still stamped with a uniquely Schindlerian character. Moreover, the spatial ideas behind the scheme and the reduction to hovering horizontal volumes bore some obvious similarities to European progressive work. Schindler’s outlook lay closer to Wright’s organic philosophy than to the mechanistic abstractions of the European avant-garde, and he seems to have come to his conclusions by his own route without knowledge of contemporary developments abroad. When he did eventually see pictures of the architecture of the 1920s created 6.000 miles away, he spoke of its apparent starkness, emptiness of spirit and lack of warmth. For him, it was the work of men who … [had gone] through the horror and alienation of trench warfare.”3 Philip Johnson (1906–2005) USA Philip Johnson is probably the most flamboyant personality in the history of 20th century architecture. He had an attitude towards architecture that one might describe as hedonistic – he wanted to derive pleasure from what he did, whether he curated exhibitions, designed houses or published books. He was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1906, and educated at Harvard University in the classics. He started his career in architecture with a joint production with the established historian Henry Russell Hitchcock. In 1932 they documented the huge output of modern architecture in Europe with an exhibition at the MoMA, called The International Style. Instead of pointing out the richness and diversity of the new architecture, they sought to find common denominators of it. They saw it as the new style. “Originally a commentator on and proponent of modern architecture, Johnson was chairman of the architecture department of the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, from 1932 to 1934 and from 1945 to 1954. Johnson began designing buildings in 1942.”4 The International Style, 1932 The term ‘International Style’, coined by Henry Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson in 1932 in their book The International Style. Architecture since 1922 characterized the prevalent features of modern architecture as it was being produced in Europe by Le Corbusier and members of the Bauhaus, among others. In their definition of the International Style they regarded the form as the most characteristic feature of the building – hence they could speak of a style. They disregarded questions of function or social content in their description. With their detailed description of what included the “International Style” they did not intend to make up a set of rules for a new architecture, but it was often taken as such of the younger generation of architects. Criticism of the concurrent exhibition on International Style: Ralph Flint in The Art News, praising the new style: “No matter how monotonous or repetitious or otherwise uninspiring the new style may appear to be in its lesser manifestations … it is probably the most powerful lever in getting us away from our jumbled aesthetic inheritances that could have been devised. After continued contemplation of the new modes, even the work of such moderns such as Frank Lloyd Wright begins to look overloaded and fussy, and we begin to eye our surroundings with a fresh severity.”5 On the other hand, H. Brock in The NewYork Times, being quite critical: “In practice, the windows are either glass sides to certain rooms or horizontal slits at about eye-level of a standing person in other rooms. Out of this simple combination must be extracted whatever interest Curtis, Modern Architecture since 1900, 232. Curtis, Modern Architecture since 1900, 235. 4 www. archinform.net 5 Quoted after Franz Schulze: Philip Johnson. Life and Work (New York: Knopf, 1994), 80. 2 3 3 fenestration may give to a façade which must, by rigid rule, have no other ornament and which, by strict dogma, must be flat and white wherever it is not glass.”6 Frank Lloyd Wright said about the International Style: “Human houses should not be like boxes blazing in the sun, nor should we outrage the Machine by trying to make dwellings places too complementary to machinery. Any building for humane purposes should be an elemental, sympathetic feature of the ground, complementary to its natural environment … But most ‘modernistic’ houses manage to look as though cut from cardboard with scissors … glued together in box-like forms – in a childish attempt to make buildings resemble steamships, flying machines or locomotives … So far I see in most of the cardboard houses of the ‘modernistic’ movement small evidence that their designers have mastered either the machinery or the mechanical processes which build the house … Of late they are the superficial, New ‘Surface-and-Mass’ Aesthetic falsely claiming French painting as parent.”7 “In fact, some architecture included in The International Style did not exhibit the properties Barr, Hitchcock and Johnson had claimed for it. The great Barcelona Pavilion, for example, the masterpiece of Mies’s erly career, was conceived as an unenclosed space defined by freestanding walls; in no instructive sense it was a volume. Furthermore, Le Corbusier’s de Mandrot Villa in the South of France was built in large parts with masonry walls that conveyed far less sense of the membranous thinness associated with the volumetric than the more customarily used stucco did. Both of these works suggested, as Philip [Johnson] himself later admitted, that the International Style had been codified too hastily from Le Corbusier’s theories as interpreted by Hitchcock. Critic Peter Blake has further recalled that more than a few people central to the modern movement ‘loathed the term [International Style] and found it insulting, just as they loathed the term ‘modernist’. They were modern architects…’ For that matter, Frank Lloyd Wright, his vitriolic conceit notwithstanding, had been perceptive enough in 1932 to apply the word propaganda to an exhibition that could have been composed quite differently with a quite different ultimate effect. When it has luck on its side, propaganda is transformed into history by a process of rhetorical alchemy. Wright knew that, too.”8 For us today it is important to identify what The International Style was meant to be and what it really was. And there, the word propaganda is quite correctly used. It was meant to promote the new, the modern architecture in a propagandistic way – and in this it was frightfully effective. The obvious downside of this success was that only a main Highway (as it was called) of architecture was promoted and the richness of stylistic, formal and functional solutions existing in Holland, France, Germany and other countries at that time was deliberately left aside. Walter Gropius (1883-1969) Germany Gropius, ex-Director of the Bauhaus at Dessau, departed Germany in 1934. He practised in England for three years before emigrating to the USA in March 1937 to take up the position of Chairman (=Dean) of the Department of Architecture at Harvard University, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. With Marcel Breuer he designed the Gropius House, Lincoln, Mass (1937), the first monument of International Modernism in the north-eastern USA. After the 1939-45 war Gropius went into partnership with several younger architects, forming the Architects Collaborative (TAC). Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) Hungary Breuer became Director of the Furniture Department at the Weimar Bauhaus in 1924. In 1928 he set up an architectural practice in Berlin. In 1935 Breuer moved to London, but crossed the Atlantic to Harvard Quoted after Franz Schulze, Philip Johnson, 80. Quoted after Curtis, Modern Architecture since 1900, 312. 8 Franz Schulze, Philip Johnson. 6 7 4 University in 1937, where he entered partnership with Walter Gropius (1937-40), and also worked as associate professor with Gropius, numbering among his students Philip Johnson and Paul Rudolph. . . . In 1946 he moved to New York city. Breuer designed several private homes in the New England states. Later works included UNESCO headquarters in Paris (1953, with Pier Luigi Nervi and Bernard Zehrfuss), the United States Embassy in Holland (1958), and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1963-66) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) Germany “Nature should also have a life of its own. We should avoid disturbing it with the excessive colour of our houses and our interior furnishings. Indeed, we should strive to bring Nature, houses, and people together into a higher unity. When one looks at Nature through the glass walls of the Farnsworth House it takes on a deeper significance than when one stands outside. More of Nature is thus expressed – it becomes part of a greater whole.” Mies van der Rohe (1958) Mies van der Rohe, ex-Director of the Bauhaus at Dessau in Germany settled in Chicago, where he became Director of the Architecture Department of the Armour Institute (later Illinois Institute of Technology). From 1940 he redesigned the campus and buildings, placing rectangular blocks on an overall grid, exposing the steel frames, and designing all the junctions with his customary meticulous care. He invented a sophisticated language of metal-and-glass architecture, used to superb effect at the Farnsworth House. This open glass-sided pavilion idea was also used by Mies at Crown Hall, IIT. Other influential buildings include Chicago’s steel-framed Lake Shore Drive Apartments and the huge Seagram skyscraper in New York, with Philip Johnson. Mies’s influence cannot be overstated . . . His impact world-wide is clear, and his metal-andglass fronted buildings have been extensively (and often unintelligently) copied. “Beyond the obvious and recurrent aspects of a Miesian style, there was an overriding intention: ‘to bring Nature, man and architecture together into a higher unity’.”9 This is an idea that, from his buildings, you would not necessarily assume – although, of course, he almost always opened up his buildings immensely towards the landscape. In Germany, Mies was increasingly rejected by two sides: by traditionalist architects for being too ‘functionalist’ and by the more radical socialist architects as using too much, highly irrelevant luxury in his buildings and being interested in a strange kind of spirituality. “When the Nazis first came to power in 1933, it seemed possible to some German modern architects that the more ‘forward-looking’ and ‘technocratic’ conservatives might wish to employ a version of modernism for state commissions: Mies was one of several […] to make an entry that year to the Reichsbank competition in Berlin. With the forced closing of the Bauhaus (of which Mies was director) in that same year of 1933, it was becoming increasingly obvious that the new regime had little time for modernism of any kind. […] In effect it was an increasingly untenable and compromised political position. In 1937 he transferred to the United States at the invitation of the Armour Institute (the future Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago. Soon after arriving, Mies van der Rohe was ‘received’ by FL Wright at Taliesin in Wisconsin. Moved by the expansive view from Wright’s hillside retreat across the vast American landscape, he declared: ‘Oh, what a realm of freedom!’”10 On Mies’s Farnsworth House “The immediacy of the primordial [original, initial] guarantees the authenticity of a vital building art. Mies’s model of the skin and bone structure, a term in which one can hear [Gottfried] Semper’s garment theory reverberate – it also learned on the art expressions of natives – only needed the approbation of suitable materials and purposes; “walrus ribs and skin” had to be exchanged for steel and glass. Mass, reduced to the minimal structure of post and beam … constructed of steel ‘trunks’ of industrial origin, embodied a technical variation of the magnified jungle shadow, wrested [snatched] not from ‘natural’ nature but from the ‘technical’ 9 Curtis, Modern Architecture since 1900, 311. Curtis, Modern Architecture since 1900, 311. 10 5 nature of the industrial age. Technical ersatz [substitute] nature replaced mimesis [imitation] of nature. With the help of girders …, Mies copied [Laugier’s] native hut for the twentieth century; in lives on in the ‘fleshless ribs’ … of the steel skeleton and its unadorned supports, which now come into the purview of art.”11 “With this theme, the reconciliation of man and Nature by means of architecture, he placed himself clearly in a tradition that had its beginnings in antiquity and has, since the villas of Palladio, affected people’s thoughts and yearnings up to the present day. … Schinkel as well as Wright have … felt themselves equally committed to this idea. They all strove in their own way for a compromise with Nature. Schinkel and Wright developed the models that Mies first emulated before rapidly finding his own way, one that he was to follow to its logical conclusion: the total opening of the structure. Perhaps more than his predecessors, however, he was at the same time conscious that the unity of the house and landscape represented an ideal that can never be fully achieved and that can only be envisioned by means of a largely intellectual approach.”12 Charles Eames (1907-1978) with Ray Eames (1912-1988) USA Charles Eames was a designer – one of the most significant and versatile of his time, also collaborating with his wife Ray (herself a distinguished painter and sculptor) in film-making, photography, exhibition and interior design. Charles Eames’s reputation as an architect rests on his own house and the John Entenza House, both in 1947. These are steel framed pavilions owing something to the work of Mies van der Rohe, and are considered important works of industrialized building. Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983) USA American inventor of the Dymaxion House (1927), evolved from aircraft and motor-car construction techniques, intended for mass production . . . While he was much concerned with the design of cheap, industrialized living-units, he also developed ways of covering large areas by means of geodesic domes constructed on the space-frame principle, using timber, plywood, metal, concrete and other materials. His US Pavilion at the International Exposition, Montreal Canada (1967) was an exemplar. Eero Saarinen (1910-1961) Finland Born in Finland. He emigrated to the USA in 1923 with his architect father, Eliel Saarinen. Eero studied in Paris, then at Yale University, and worked with Charles Eames. With Eames, he designed moulded plywood chairs in the late 1930s, and other furniture in his own right. He became closely involved in architecture after the end of the 1939-45 war. Eero worked with his father from 1937, setting up his own practice in 1950. Notable buildings include an auditorium and chapel at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ice Hockey Rink at Yale University, and two airport termini – Kennedy International Airport in New York and Dulles International Airport near Washington D.C. Saarinen was one of two architects on the four-person international panel appointed to judge entries for the Sydney Opera House design competition of 1956. Paul Rudolph (1918-1997) USA Paul Rudolph studied with Walter Gropius at Harvard before setting up in practice in 1947. Rudolph was Chairman (= Dean) of the Department of Architecture at Yale University 1958 to 1965; while there he designed the monumental (and infamous) Art & Architecture Building (1958-63), typical of his brutalist architecture. 11 12 Fritz Neumeyer, The Artless Word (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991), 129. Wolf Tegethoff: Mies van der Rohe: The Villas and Country Houses (New York: MoMA/MIT Press, 1985), 130.

© Copyright 2026