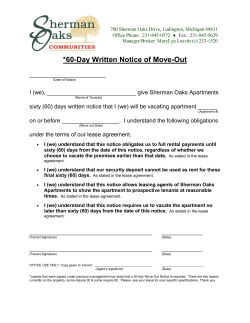

Document 151234