View/Open

I

\

FEDERA TION MUSEUMS

JOURNAL

,

VOLOME X

NEW

SERIES

for

1965

I'

lOHORE LAMA EXCAVATIONS, 1960

\

by

WILHELM G. SOLHEIM II

AND

ERNESTENE GREEN

\

\ I

\

.

KP

JB 42

MUSEUMS DEPARTMENT, STATES OF MALAYA

KUALA LUMPU'R

/

FEDERATION MUSEUMS JOURNAL

VOLUME X NEW SERIES

MUSEUMS DEPARTMENT

STATES OF MALAYA

KUALA LUMPUR

for 1965

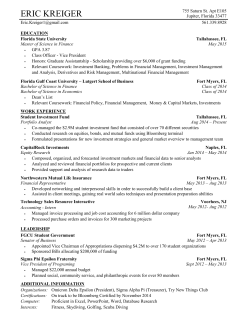

JOHORE LAMA EXCAVATIONS, 1960

Wilhelm G. Solheim II and Ernestene Green *

INTRODUCTION

Johore Lama is the site of a Malayan town which during the Sixteenth

Century was the royal capital of the kingdom of J ohore. It is located almost

at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, at 104° O'E, 1°34' N. The mouth

of the Johore River (Sungei Johor) is directly east of Singapore Island. The

site of Johore Lama is on the east bank of the Johore River, approximately

ten miles north of the river mouth.

The surrounding area is swampy and generally

cultivation. However, it is fairly well located to take

the Malacca Straits. Apparently, it was this trade

resource of the town and its royal inhabitants during

unsuited for intensive rice

advantage of trade through

which provided the main

the Sixteenth Century.

Previous Excavation

First mention of the ruins of this city was made by J. R. Logan in 1847.

No excavations were undertaken at the site, however, until 1932-35 when

G. B. Gardner visited several archaeological locations along the Johore River,

J ohore Lama among them. Gardner collected porcelain and earthenware from

the ruins. In 1936 Quaritch-Wales also visited sites on the Johore River and

excavated several trial trenches at Johore Lama. He states that deposits here

seldom exceed 18 inches. 1 Between 1948 and 1954 several surface collections

were made at the site.

During 1953 several investigators worked at Johore Lama. A preliminary

survey of the earthworks of the fortified city was made by P. D. R. WilliamsHunt and Paul Wheatly in March of that year. In the course of the survey

they cleared the jungle from about 1,100 yards of the ramparts. G. de G.

Sieveking and students from the University of Malaya conducted excavations

at Tanjong Batu (the fort) in August, 1953. These excavations are summarized

in the section titled "Excavation and Clearance" below.

1960 Excavation

In 1960 the senior author was asked by the Federation of Malaya to assist

members of the National Museum in the excavation and reconstruction of the

fort at J ohore Lama, to recommend future archaeological work in Malaya, and

to begin a study of the locally made Malayan pottery. This report is the

'" The fi~st portion of this report was written jointly while the portion on the pottery and

what follows were wntten by the senior author.

1 WALES, 1940, 63.

FEDERATION MUSEUMS JOURNAL X

(1965)

second of a series concerning excavation and reconstruction at the site. 2

Excavation of the fort was done jointly with Mr. John Matthews, at that time

Curator of Museums for Malaya.

There were two interrelated purposes in the excavation of the fort at Johore

Lama. The first was to reveal by archaeological methods that portion of the

history of the site when it was a royal capital and to solve certain problems,

unclear in documentary sources, concerning its destruction. Secondly, excavation

was undertaken to discover the approximate appearance of the fort in the

Sixteenth Century, in order that the architectural features might be reconstructed,

as accurately as possible.

During excavation and restoration of the fort, some time was spent in

exploration of the total fortified area and the immediate neighbourhood of J ohore

Lama as well as other historic sites farther up the Johore River. In the

exploration of the fortified area an unusual grass covered mound was discovered

in the east corner of the general area considered by Gibson-Hill as the possible

site of the palace. 3 Preliminary investigation of this mound indicated that it

was primarily made up of potsherds. As no explanation of the mound could

be presented by the owner of the land on which it stood, or by other inhabitants

of the kampong, it was decided that it would be worth spending some time

in excavation to see whether it might have some connection with the palace.

There was no local name for this mound, so it is referred to as the "heap."

The great majority of the pottery described herein came from the "heap,"

so a description of its excavation is presented in detail. Final work "'at the

site included a partial reconstruction of Tanjong Batu. The six excavated gun

embrasures were rebuilt approximately in their assumed condition prior to

destruction, and the earth rampart around these embrasures was rebuilt. The

soil used in reconstruction was hauled from a ditch southeast of the fort,

probably the source of the earth used to build the original wall of the

fortification.

HISTORY

In A.D. 1511, the town of Malacca, capital of the Malay kingdom, fell to

the Portuguese, and the Malay ruling family moved southward. While in control

of Malacca the royal family and their followers capitalized upon the city's location

as a trading centre and entrepot to become prosperous. When they lost the

city they also lost their means of support and had the choice of either finding

another source of revenue or of accepting a lower standard of living. The

defeated Sultan did not immediately establish another capital, but lived in a

series of towns on the Johore River or 011 the Island of Bintan, south of Singapore,

while trying to find an advantageous location for another capital. The J ohore

2 SOLHEIM,

1960.

3 GIBSON-HILL,

1955, 152.

2

SOLHEIM & GREEN

on

JOHORE LAMA EXCAVATIONS

Lama area was not satisfactory for the production of rice, nor was it as well

situated for a trading centre as Malacca. Nevertheless, the Sultan, Ala'u'd-din,

probably felt it was the best of the choices available and in the early 1540's

decided to establish the royal capital south of the already existing kampong

of Johare Lama.

The kingdom of Johore was not to remain unchallenged, for sometime

between 1551 and 1568, probably 1564, the Achinese attacked the city and

captured the Sultan, Ala'u'd-din. The city was burned and the Sultan taken

to Acheh and there killed.

This, however, did not end the J ohare kingdom; Ali Jalla, a son of the

former Sultan and a non-royal wife re-established Johore Lama as the royal

capital. He was apparently in alliance with the Portuguese against the Acheh.

This somewhat friendly, if strained, situation did not last long, for in 1582 a

Portuguese trading vessel was wrecked at the mouth of the Johare River, and

its cargo rescued by Ali Jalla. Although the Sultan promised return of the

goods, he recanted his decision and sold or kept most of the merchandise. This

event ruffled the friendship between the Portuguese and Johore, but it was not

as important in the succeeding hostilities between the two as an order from

Portugal forbidding any Malaccan to have a factor in a P9rt of Johore. Soon

after the order was issued in 1684, an Achinese captain attempted landing at

Johare Lama, but the Portuguese intercepted him and escorted the ship to

Malacca. Ali Jalla protested, but the arrival of two Portuguese galleons at

Malacca checked any show of hostility. Apparently, the motive for sending

the Portuguese galleons was not as much a fear of Johore as the fear of an

Achinese attack on Malacca. The Malaccan situation appeared quiet and the

force soon returned to India.

Almost immediately after the departure of the galleons Johore was at war

with Malacca. In reaction to the Portuguese order that all ships dock at Malacca

Ali Jalla sent out a fleet to force them all to stop at Johare Lama. The result

was a famine in Malacca, due to the loss of food shipments. Furthermore, Ali

Jalla unsuccessfully attacked Malacca in January 1587, after which the Portuguese

dispatched a party to Goa to acquire more ships. These reinforcements joined

the pre-existing Malaccan fleet already located at the mouth of the Johare River.

The following day they sailed upstream to Johore Lama. For several days the

city was simply bombarded while raids were made on places farther up the

river. The arrival of still more vessels signalled the Portuguese attack on the

royal city of Johare.

The city of Johare Lama consisted of two parts at this time, the kampong

called "Corritao," a suburb located on a protrusion of land extending into the

Johore River, east of the mouth of the Johore Lama River, and the fortified

portion of the city, west of the kampong. The fortified section was a roughly

rectangular earth-walled area with an entrance on the west, the side toward the

3

FEDERATION MUSEUMS JOURNAL X

(1965)

Corritao. The strong point of the walled area was a fort located on a point

of land extending slightly into the Johore River. This point was called Kota

Batu and the fort was named Tanjong Batu. The fort, however, was on the

east side of the city, the opposite side from the Corritao suburb. Portuguese

accounts mention the artillery which defendants of J ohore Lama possessed. 4

Not only were muskets mentioned, but also bronze cannons of the types called

Moorish basilisk, serpent, lion, large camel, camellete, and falcon. Many of

these were housed in the fort, as this was the city's strong point.

The initial Portuguese assault was not made on the fort, but "at the corner

which lies directly above Corritao, because there only there was no ditch."5

In other words, the attack was from the west, across Corritao suburb, and

through the west entrance of the fortified portion of the city. Despite rather

stiff Malay resistance, the Portuguese attackers advanced across the city and

to the fort, which was taken. The Portuguese then set fire to the city.

Johore Lama never again served as a formal residence for the Malay court.

However, the site does seem to have been reoccupied after the Portuguese attack,

and to have been a place of some importance when the capital was further upriver.

"It is extremely likely that there was provision for temporary habitation there

during the period 1688-1720, if not earlier, to serve when breaking the journey

up and down the river, or as an occasional residence."G There is no evidence

of a reconstruction of the fortifications at Tanjong Batu, and we may assume

that the site served only as a habitation area for local residents and as a temporary

stopping place for royal personages.

With the above knowledge of the history of J ohare Lama, we could expect

the following archaeological remains: evidence of a living area, Corritao, outside

the earth walls; remains of earth walls surrounding another living area, palace,

and probably business district; remains of the fort at Kota Batu; evidence of

two attacks, one in 1564 and another in 1587, in the form of layers of burned

material and charcoal, and materials of war such as cannon balls, musket balls,

etc.; and evidence of residence at the site after 1587.

EXCAVATION AND CLEARANCE

J ohore Lama consists of two parts:' a suburb called the Corritao or Kampong

Johore Lama, located southeast of the mouth of the Johore Lama River, a

tributary of the Johore River, and northwest of the walled portion of the city;

and the fortified portion, a roughly rectangular-shaped area bounded on the

west, north, east and southeast by ridges representing the original earth wall

surrounding the city (Map 1). During occupation the earth wall extended along

4

MACGREGOR,

5 MACGREGOR,

G

GIBSON-HILL,

1955, 106-12.

1955, 109.

1955, 167.

4

facing page 4

JOHORE

LAMA

Map I

_;-=L=--..,.~,

i

fJ,O,!-I'."

t

T

J'NP.lrtd.6"~

.'IM.HAuIO'.i

(.'It,ek,,~ 6J1

~,*~/,4.C"...., IO."Jllf"

{'b;

6'lIn111.. ..

t4t; 1W"",f.m"

·ltJ.~.".

'l'1"'""w... brUWoll.,II<oINolo~.1Il.,II

(I)~,,.. (J

'-do

fr

~

S..... ",.

,,.,,01

tilhMTnlIcCoo.....

5.0104

l'IIlar

Hofopon(.)~7(21_

Io. I Iw.Uk lJ&b'T...

fl.<.-kl.lflK'..... O'Cll'IcT._lo

'.......... '.I0,....

•

0

T_ .........,. ••

n

1'101&1••

,.,"_li_, flpo

TtoooMliW Hr.... a-o.rlc Holt"'. toIK'.. Ho;p<.

e-_..;,uo .......

,,..Wot"s.._,.LalMt.co_,..,••.

••

•

(II St,t\oIl'IOlfo<wo

0111....1'001

V·,··.-..

...·1$4.1

,;1$.1.",0

••• ~~~

5lf'O,,....,.."

w

..ktlI111o""', (1IClltt

To_Cow.. hoIio.Sut-. ' ...... Coe<Rc.WolL

"""'.. , , "..... (11l.u4(1)t1d(JILo'*"

T~.. t>~1*

~ .,14,0, C~,",..

(llh.b....k"'.1l1

l,on.,.,...

. __

_"fl'~('IPoni.

••••••••

....

!"-

''''~Dr'''' I'Iaooa<fO...... hrUlW.IL "-rWd •••••••••••• t.O.

,('I GIWIoM'"

'"" ""'" 11-., ........

•• _•.•••••.••• _ . , _ . _ ; _ . - " . _

'"

[)

IH ~i:,~;ul"

~

(S)

~oIIwI,

••

10. (JI"n"!..... II"Jc....t

sc.u... ",.,,

~. lI...... s,,""'1li'O"

W..,.HoltO Gaoop

.

Io,..

T.C.

....

Reproduced by pennission of the Director

of National MaPPIng, Malaysia, Government

copyright reserved.

SOLHEIM & GREEN

on

JOHORE LAMA EXCAVATIONS

the south side of the city also, but now has fallen into the J ohore River. This

fortified area extends diagonally between two low hills. The southern limit is

on the crest of Kota Batu hill, where the coastline forms a point projecting

into the Johore River. This combination of hill and projection into the river

makes the point a lookout spot, and it is here that the fort, Tanjong Batu, was

built. The northern limit of the fortified area is on the tip of another low hill.

The main portion of the fortified area is on the saddle between these two hills

and between this and the river bank.

Investigations in both 1953 and 1960 included partial excavations of the

fort, which juts off from the southeast corner of the fortified area to form a

northeast-southwest trending rectangular sector. It is walled on the west, east,

and south sides, the north side opening into the main fortified area (Map 2).

The excavations directed by Sieveking in 1953 were concentrated on this feature.

Two trenches were dug, one adjacent to a dip in the earth wall on the side

overlooking the anchorage, and the other at the southeast corner of the fort.

The first trench, approximately 12 feet wide and carried to two feet below ground

level inside the fort, revealed timber and stones interpreted by Sieveking as a

collapsed gun platform. The second, at the corner of the seaward facing

rampart, disclosed several courses of masonry which were believed to have been

a skirting wall on the exterior of the earth rampart. 7

The 1960 excavations were planned to answer several questions concerning

the fort: the nature and construction of the walls, and their vertical, horizontal,

and lateral extent; the relation of the walls to the ground level during occupation;

the meaning of the nine dips in the walls; the use of the area within the fort;

and the history of the fort, as reflected in the stratigraphy. Furthermore, the

excavations were planned to answer specific questions, such as that concerning

the masonry course found in 1953. Was this a wall skirting the exterior of the

earth rampart, or did this wall serve another function? In order to take full

advantage of the previous excavations, especially those at the southwest corner

of the fort, the trench excavated at this spot in 1953 was enlarged and deepened

(WWI, Map 3).

FORT WALLS

Trench:

West Wall I

Description: This was the only trench which exposed a corner of the

fort, and therefore was somewhat more elaborate than the other wall trenches.

Three intersecting excavations were made: one along the north wall; one along

the west wall; and one through the corner, extending from the exterior to the

interior of the wall. The latter was actually a re-excavation and extension of

two separate unauthorized excavations made sometinle between the 1953 and

the 1960 work. All three trenches joined at the northwest corner. Porcelain,

7

GIBSON-HILL,

1955, 136-38 and

SIEVEKING,

5

1955a, 199.

FEDERATION MUSEUMS JOURNAL X

(1965)

stoneware, and earthenware were found in all portions of the trenches. Fallen

stones from the wall were found near the surface in the trenches outside the

walls.

The portion of the trench along the west wall was so placed to explore

the vertical extent of the stone wall. This trench revealed the stone wall

mentioned by Sieveking to be a foundation for the overlying earth wall, rather

than a course of stones skirting the earth wall. The stone foundation at the

corner was approximately 5 feet high and consisted of two different types of

construction. The lower portion was of rough, unshaped stones which had been

set directly on the original surface of the hill.. The upper portion of the stone

base was of regularly shaped stone blocks (called "older Alluvium" by GibsonHiIl 8), at this point three or four courses high (Plate la-b). Only the upper

part of the foundation was visible during occupation, as the lower portion was

below the new ground surface. The corner itself consisted primarily of shaped

stones from the top of the foundation to the base, with one narrow layer of

unshaped stone between the fourth course and the deepest shaped block; thus

the foundation layer of unshaped stones did not extend completely to the corner,

but ended a slight distance from it. A two-inch thick layer of lime was spread

over the top of the foundation, but not on the sides. This construction appeared

on both the outside and inside of the for1 wall. Portions of this lime layer

can be seen above the coral blocks to the left in Plate la.

The trench along the west wall showed two narrow layers with varying

amounts of charcoal in them and separated by a thicker layer of soil. Below

the second layer, in the south end of this trench was a somewhat rectangular

volume of earth, running parallel with the wall, in which there was a heavy

concentration of charcoal (Plate Ib and IIu). A narrow extension of this can

be seen in the west wall of this trench (Plate lIb-c). Dark patterns of post

holes in the earth, which was somewhat more yellow than most of the surrounding

earth, were present in the bottom and west side of the trench (Plate IIb-c).

Large carbonized remnants of a post were found just around the corner by the

north face of the wall (Plate Ie). This was not in evidence above the level seen

in Plate IlIa). Next to it, but at a lower level, was a flat circular stone with

no indications of a post hole above it (Plate IlIa). The cut stones of the

north wall were leaning out at a slight angle from the corner and along the

wall for the length of three cut stones. A good sized tree root was growing

into the wall between the third and fourth cut stones from the corner. Below

the three courses of cut stone the unshaped stone extended out into the trench

six to ten inches (Plate IIlb), a situation found nowhere else on the wall. The

stratigraphy evidenced in the east end and north side of the trench along the

north wall was badly confused with patterns of numerous post holes, some

crossing or extending into others, all indicating a major disturbance in this area.

8 GIBSON-HILL,

1955, 136.

6

facing page 6

DETAILED SURVEY

OF

JOHORE LAMA

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

Scale: I inch to 100 links (or 66 feet)

I

,,/

Reproduced by permillion of the D'

of N

l ' Malaysia, Government

rrector

aIhonafMappmg,

copyng t reserved,

Map II

Sale: Ilncllol6lltt

• • )I )0

~"

(I 0

I ! I

I

"

. I

"I

I•

I

..

'"

..

© Copyright 2026