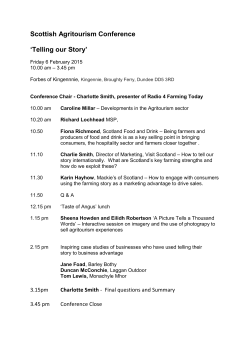

the STRATEGY - N-56