Maternal responses to childhood fevers: a comparison of rural

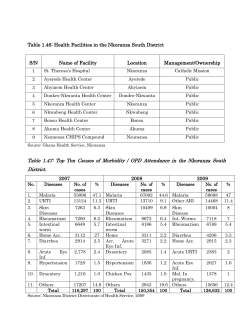

TMIH489 Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 Maternal responses to childhood fevers: a comparison of rural and urban residents in coastal Kenya C. S. Molyneux1,2, V. Mung’ala-Odera1,T. Harpham3 and R.W. Snow2,4 1 2 3 4 Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)/Wellcome Trust Centre for Geographic Medicine Research, Kilifi, Kenya Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK The Kenya Medical Research Institute/Wellcome Trust Collaborative Programme, Nairobi, Kenya Department of Urban Policy and Planning, South Bank University, London, UK Summary Urbanization is an important demographic phenomenon in sub-Saharan Africa, and rural-urban migration remains a major contributor to urban growth. In a context of sustained economic recession, these demographic processes have been associated with a rise in urban poverty and ill health. Developments in health service provision need to reflect new needs arising from demographic and disease ecology change. In malariaendemic coastal Kenya, we compared lifelong rural (n 5 248) and urban resident (n 5 284) Mijikenda mothers’ responses to childhood fevers. Despite marked differences between the rural and urban study areas in demographic structure and physical access to biomedical services, rural and urban mothers’ treatment-seeking patterns were similar: most mothers sought only biomedical treatment (88%). Shop-bought medicines were used first or only in 69% of the rural and urban fevers that were treated, and government or private clinics were contacted in 49%. A higher proportion of urban informal vendors stocked prescription-only drugs, and urban mothers more likely to contact a private than a government facility. We conclude that improving self-treatment has enormous potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in low-income urban areas, as has frequently been argued for rural areas. However, because of the underlying socio-economic, cultural and structural differences between rural and urban areas, rural approaches to tackle this may have to be modified in urban environments. keywords malaria, maternal treatment-seeking, shops, health facility access, Kenya correspondence Sassy Molyneux, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)/ Wellcome Trust Centre for Geographic Medicine Research, P.O. Box 230, Kilifi, Kenya. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction The majority of the sub-Saharan African population live in rural areas. However, the region currently has the highest rates of urbanization in the developing world (Brockerhoff & Brennan 1998), two-fifths of which has been attributed to rural-urban migration (Chant & Radcliffe 1992). With mounting international concern about the health status of rapidly growing low-income urban communities (Harpham 1997; Gould 1998), an improved understanding of the way in which these demographic processes influence treatment-seeking patterns is urgently needed (Tanner & Harpham 1995). Household responses to illness are influenced by socioeconomic and cultural factors (Kleinman 1980; CunninghamBurley 1990) and by ease of access to treatment sources (Stock 1985; Kloos et al. 1987; Mburu et al. 1987; Glik et al. 1989). In sub-Saharan Africa, rural and urban populations 836 differ demographically, in socio-economic and cultural composition, and in proximity to formal and informal treatment sources. Urban populations are generally younger, better educated, and more ethnically heterogeneous than rural populations. Government health services, private practitioners, pharmacies and shops selling over-the-counter medications are concentrated in urban areas. These rural-urban differences imply that urban residents use biomedical (or ‘modern’) services and drugs more often and at an earlier stage than rural residents, and that rural residents more readily turn to biocultural (or ‘traditional’) therapy. Urbanization patterns observed all over sub-Saharan Africa are reflected in Coastal Kenya, where urban growth has centred on Mombasa, the second largest city in the country. Coastal Kenya is a malaria-endemic area, and malaria is the principal cause of childhood mortality. Fever is a key symptom of uncomplicated malaria, but can rapidly develop into © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 C. S. Molyneux et al. Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya severe, life-threatening malaria if not treated with appropriate antimalarials. This study aimed to compare the treatment-seeking patterns of rural and urban residents of the dominant ethnic group in Coastal Kenya, the Mijikenda. The focus was on Mijikenda mothers’ responses to uncomplicated childhood fevers. Materials and methods Study populations Using a standard definition of ‘urban’, i.e. ‘a proclaimed urban centre/town/city with a population of 10 000 or more’ Figure 1 Location of the study area. (Parry 1995), one rural and one urban area were selected for the study. A 446.6-km2 area to the north and south of Kilifi Town was selected as the rural study area (Figure 1). The population consists largely of Mijikenda farmers who supplement subsistence incomes with cash crops and remittances from family members working in the nearby urban centres of Kilifi, Mombasa and Malindi. The Mijikenda family system is patriarchal and polygamous. The geography, demography, anthropology and disease ecology of the area has been described in detail elsewhere (Parkin 1991; Snow et al. 1994). Ziwa la N’gombe, a 0.6-km2 area on the outskirts of Kilifi District Rural study area sub-section Rural study area (444.6 km2) Kilifi creek Mtwapa creek Mombasa District Urban study area (0.6 km2) 25 km © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd 837 Tropical Medicine and International Health C. S. Molyneux et al. volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya Mombasa City, was selected as the urban study area (Figure 1). Ziwa la N’gombe is approximately 60 km from the rural study area, and has the low-income, densely populated housing characteristics common to Mombasa and other urban areas of East Africa. Household incomes are derived largely from formal and informal work in and around Mombasa, much of which is linked to the tourism industry. The history, geography and demography of Mombasa city have been described elsewhere (Kindy 1972; Government of Kenya 1990; Bambrah 1996), and a number of studies offer an insight into the lives of the city’s residents (Parkin 1979; Mazrui 1996; Malombe & Kanyonyo 1997). Mapping and enumeration The position of every household, shop, pharmacy and health facility in both study areas was recorded using hand-drawn maps. Maps were used to conduct a census of every resident in each household. To ensure consistency in mapping and enumeration, a household was defined as ‘a person or group of people living in the same house, who are answerable to the same head and share a common source of food and/or income’. People were regarded as resident if they had a sleeping place within a household and had already or intended to remain there for a total of at least six months. The six-month ‘cut-off’ in defining residency was based on extensive pilot work in and around both study areas. To identify the relative position of households to each other, and to every possible treatment source, digitized maps were developed for a subsection of the rural study area (Figure 1) and the entire urban area using a combination of scanned hand-drawn maps and a hand-held satellite navigational system (SatNav® Trimble Navigation, Europe Ltd, UK). Digitized maps were computerized using the software package MapInfo® (Troy Ltd, USA). All shops and pharmacies on the digitized maps were revisited, and an audit taken of all antimalarials stocked. Semi-structured interviews were also held with a range of health care providers. Mothers’ survey Consenting mothers from the samples were interviewed. In addition to socio-economic and demographic data, illness histories over the last two weeks were taken for all resident children aged 6 months up to the 10th birthday. For each illness episode, details were documented on symptoms and their perceived severity, duration, types of treatment sought, and from whom and at what stage of the illness treatment was sought. Data were entered onto closed and coded questionnaires developed through pilot work. Several questions included specified prompts to facilitate data accuracy and comparability. Data quality and analysis Ten Mijikenda fieldworkers were carefully trained using participatory approaches in communication skills, form-filling and demographic techniques. All data were double-entered and verified in Foxpro (Version 2.6) and subjected to range and consistency checks. Inconsistencies were verified in the field through re-interview. Rural and urban mothers’ characteristics and treatment-seeking patterns were compared using x2-tests (for proportions) and 2 sample t-tests (for continuous variables) in SPSSV6. Results Basic demographics Estimated coverage of the census work in both study areas was over 95% of the total population. The demographic structure of the populations is presented in detail elsewhere (Molyneux et al. 1999a). Briefly, 82 594 people were enumerated in 7788 households in the rural area surrounding Kilifi town (446.6 km2). 14 885 people were enumerated in 6458 households on the outskirts of Mombasa city (0.6 km2). Urban households were generally smaller (mean 2.34; median 2; interquartile distance 2) than rural ones (mean 10.6; median 9; interquartile distance 8). Sampling of mothers Following the census, random samples of rural and urban resident women aged 15 years or above with the prime responsibility for at least one resident child aged 6 months up to the 10th birthday were interviewed in order to obtain more detailed information. Rural resident mothers were initially sampled from a survey of all women’s birth histories. In follow-up interviews Mijikenda mothers who had never lived in an urban area were identified. Urban resident Mijikenda mothers were sampled from the census, which was structured to enable the identification of lifelong urban resident mothers, and mothers who had immigrated from a rural area. 838 Physical access to health services GIS software was used to identify the ratio of residents to the shops selling antimalarials, pharmacies, trained community health workers (CHWs), private clinics and government dispensaries in and around the subsection of the rural and the entire urban study area (Table 1). Shops were defined as structures (ranging from temporary stands to permanent buildings) which sell over-the-counter drugs as well as a number of other everyday goods. The majority of shops dispensed antipyretics; 73% of rural and 96% of urban shops sold antimalarials, and a review of stocks was allowed in 92% of these © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 C. S. Molyneux et al. Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya Table 1 Availability and access to treatment sources in the study areas Shops Shops selling antimalarials Pharmacies Community Health Workers Private clinics Government dispensaries Total interviewed Rural study area* Number of Ratio ** facilities facility:people Urban study area Number of Ratio ** facilities facility:people 159 116 000 022 009 003 203 143 137 003 007 009 000*** 162 1 : 218 1 : 299 – 1 : 1714 1 : 3857 1 : 11570 – 1 : 109 1 : 114 1 : 5210 1 : 2232 1 : 1736 – – * based on mapping and enumeration in the rural subsection (Figure 1). ** based on total population estimates of rural subsection and urban area (n 5 34 712 and 15 629, respectively) *** the nearest government dispensary is situated approximately 1.5 km from the urban study area. shops (Table 2). Of note is that 7% rural and 40% urban shops had in stock either sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (proprietary name Fansidar) and/or amodiaquine (proprietary name Malaratab), over the study period prescription-only drugs in Kenya. In addition to greater access to these drugs through the informal sector, urban residents also have access to them from the three pharmacies. Community-based health care was evident in both study areas. CHWs have been trained to supply a limited range of drugs at subsidized rates from their homes, and to refer patients to other facilities when necessary. Interviews revealed that CHWs in the rural area varied in availability and activity, and that in town they were not operating at all. In both areas problems were largely due to failures in drug supply. Alternative therapy sources include the peripheral government services (or dispensaries) and private clinics. Dispensaries operate on a cost retrieval basis, charging approximately 20–40KSH (20–40 pence) to treat a febrile child. Complications are referred to the nearest District Hospital. Private clinics are relatively expensive: rural and urban practitioners charge approximately 150 and 250KSH, respectively, to treat a febrile child. Traditional healers were not mapped but discussions revealed good physical access to a variety of healers (waganga) in both study areas. Waganga are distinguished primarily according to whether they are wa ramli (who diagnose) or wa kutibu (who treat), and secondarily by their field of specialization, of which there is a wide range. Waganga in both areas differ greatly from each other in their reputation and charges. The urban population has a lower ratio of people to shops, pharmacies and private clinics than the rural subsection population, and the latter has a lower ratio of people to CHWs and government dispensaries (Table 1). However, all urban residents live within 1 km of all facilities, and the nearest © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd government dispensary is a short bus ride or half-hour ‘quick walk’ away. 87% of the rural study area homesteads live within 1 km of a shop, 55% within 2 km of a CHW, and only 32% within 2 km of a private clinic and/or government dispensary. The urban population therefore has better physical access to informal and formal biomedical services in and around their area of residence than the rural population. In addition to these services, the rural study area subsection is transected by the main Malindi-Mombasa road which, together with a number of tarred roads, provides the population access to the administrative township of Kilifi, where the district hospital and 5 private clinics are situated. The central point of the rural subsection is approximately 10 km from the district hospital, and over 66% of households Table 2 Availability of proprietary antimalarials in the study area shops Proprietary drug name Rural shops (n 5 108)* Urban shops (n 5 125) Chloroquine generic† Dawaquin – adult† Dawaquin – junior† Malaraquin† Homaquin† Oraquin† Rohoquin† Laraquin† Maladrin† Fansidar‡ Malaratabs§ Camoquin§ 01 32 12 91 26 13 00 00 03 00 08 00 005 061 031 118 061 025 001 002 015 002 050 003 * based on mapping and enumeration in the rural subsection (Figure 1). † chloroquine-based; ‡ sulphadoxine–pyrimethaminebased; § amodiaquine-based. 839 Tropical Medicine and International Health C. S. Molyneux et al. volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya Mothers’ characteristics Age , 35 years $ 35 years Marital status Unmarried Married Religion None/traditional Christian/Muslim Formal education None $ standard 1 Earns any cash None Yes Children , 10 means (SD) Household type Nuclear Extended Husband’s residence Household Elsewhere Table 3 Characteristics of lifelong rural and urban resident sample of mothers Rural percentage (n 5 248) Urban percentage (n 5 284) 64 36 81 19 , 0.0001 13 87 20 80 , 0.05 70 30 32 68 , 0.0001 74 26 44 56 , 0.0001 44 56 02.5 (1.2) 40 60 01.9 (1.0) 5 0.455 20 80 68 32 , 0.0001 68 32 93 07 , 0.0001 P–value* , 0.0001 * Derived using x2-tests and (for the continuous variable) a two sample t-test. are within 2 km of a bus stop. The urban study area is situated alongside the Malindi-Mombasa road, and a constant flow of buses and taxis ensures good access to health services available elsewhere in the city. Mombasa District Hospital is situated about 3 km from the urban study area. Mothers’ characteristics 248 lifelong rural and 284 urban resident mothers participated in the detailed survey interviews. Their mobility patterns and the ties maintained between rural and urban areas are described in detail elsewhere (Molyneux et al. 1999a). It should be noted, however, that most (87%) of the urban sample were born in a rural area, and had initially migrated to town to stay with relatives (83%), primarily husbands. The majority were familiar with the urban environment before moving, were supported socially, economically and with some form of housing on arrival in town, and intended to return to live in a rural area in the future. One third had spent at least 10% of nights elsewhere in the year preceding the interview or since migration into their current household. Much of this ‘circulation’ (76%) was to rural areas. The rural and urban samples differed significantly in many of their characteristics (Table 3). Rural mothers were generally older, cared for a greater number of children 840 , 10 years, were more likely to be married, more likely to follow traditional beliefs, and less likely to have received any formal education than urban resident mothers. They were also more likely to live in extended households, and to have husbands resident elsewhere, primarily in town. Rural and urban mothers did not differ significantly in their likelihood to be earning some form of income. The majority of those earning money were involved in small-scale businesses in and around their communities. Treatment-seeking for uncomplicated childhood fevers During the course of the interviews, childhood fevers in the two weeks preceding the interview were identified. A total of 317 childhood fevers were reported, 95% of which received some form of therapy. The types of action taken and the stage at which they were taken are shown in Table 4. The most common actions were the purchasing of shopbought drugs (47%), visits to private clinics or hospitals (20%), and other forms of therapy in the home (12%). Visits to government hospitals constituted 10% of the actions taken. Home treatment and the purchasing of shop-bought drugs generally took place on the same day or the day after symptoms were first observed (67%). Clinics, dispensaries and hospitals were more likely to be contacted on the second © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 C. S. Molyneux et al. Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya Table 4 When and where mothers responded to fevers Home treatment Shop drugs Private clinic/hospital Government clinic/dispensary Government hospital Healer Other Lifelong rural resident mothers ——————————————–––––––– Actions (%) % actions taken on n 5 147 day 0 and 1* Urban resident mothers —————————————––––––––— Actions (%) % actions taken on n 5 236 day 0 and 1* 09 48 15 06 16 03 03 13 46 24 03 07 06 01 69 79 43 67 27 00 – 59 64 40 28 25 07 – * Day 0 is the day the symptom was first observed. day or later (62%). The proportion of each action taken on day 0 or day 1 was not significantly associated with rural or urban residence. However, for some actions the numbers are very small. Mothers’ treatment-seeking patterns for each fever were grouped in several ways (Table 5). Distinguishing between biomedical (‘modern’) and biocultural (‘traditional’) actions, most responses to fever were biomedical: only 12% of fevers were treated with herbs and/or by healers instead of or as well as with biomedical therapy. Of the group who administered biocultural therapy, a healer was consulted in 4 instances by rural mothers and in 11 by urban mothers. A total of 13 treated fevers were not treated outside the household using biomedical therapy. Of those that were (91% of all reported fevers), the most common responses were to administer shop-bought drugs only (49%), and to consult a private practitioner (29%) or government service (19%). The sequence of biomedical actions taken shows that most fevers treated outside the household were treated using shop-bought medications only or first (69%). Lifelong rural and urban resident mothers’ treatmentseeking patterns were compared in three ways (patterns defined as ‘other’ were excluded): biomedical only (n 5 176), or biomedical and/or biocultural actions (n 5 36); biomedical actions outside the household were shops only (n 5 141), and/or government/private services (n 5 139); • • Table 5 Treatment-seeking for fevers in the last two weeks Type of therapy used Biomedical only Biomedical and/or biocultural Total Type of biomedical service used* Shop-bought drugs (SDs) only SDs and/or government service only SDs and/or private practitioner only Other Total Sequence of biomedical actions* Shop-bought drugs only Shop drugs r clinic/hospital r Clinic/hospital Other Total Lifelong rural resident mothers n (%) Urban resident mothers n (%) 119 (90) 013 (10) 132 (100) 147 (86) 023 (14) 170 (100) 065 034 024 003 126 (52) (27) (19) (2) (100) 076 020 061 006 163 (47) (12) (37) (4) (100) 065 022 038 001 126 (52) (17) (30) (1) (100) 076 036 046 005 163 (47) (22) (28) (3) (100) * Does not include fevers which were not treated outside the household, or were only treated by a healer (6 rural and 7 urban fevers). © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd 841 Tropical Medicine and International Health C. S. Molyneux et al. • Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya sequence of biomedical actions taken outside the household was shops only/first (n 5 199), or direct contact of a government/private clinic or hospital (n 5 84). With respect to therapeutic approach and sequence of biomedical actions taken, patterns were similar with no significant differences between rural and urban mothers. However, there was a significant difference between in the type of biomedical services contacted (x2 16.71; P , 0.001): urban mothers were almost twice as likely as lifelong rural resident mothers to consult a private clinic, and less than half as likely to consult a government service. To explore variation in treatment-seeking patterns, rural and urban mothers’ responses were combined and compared by a range of demographic and socio-economic variables. These included child’s age, mothers’ age, religious affiliation and education, whether or not the mother was earning some form of income, and (for urban mothers) length of urban residence. The only differential demonstrating a significant association was age of sick child. Younger children (, 5 years) were more likely to be taken directly to a clinic or hospital than children (x2 5 years (> 12.41; P 5 0.002). In informal discussions, mothers explained that younger children are less able to take tablets, less able to explain what they are suffering from, and more vulnerable to illness. Discussion Urbanization is an important demographic phenomenon in Africa, and the health of a growing low-income urban population a cause of mounting international concern. Of interest to health planners is the extent to which health service provision is meeting the changing health needs of urban populations, and whether there are rural and urban differences in responses to potentially life-threatening illnesses such as malaria. On the malaria-endemic Kenyan Coast, urbanization is centred around the city of Mombasa. Through our study framework we identified a group of rural resident mothers who had never lived in an urban area, and a group of urban resident mothers who were mostly rural-urban migrants. Both groups were Mijikenda, the dominant ethnic group in Coastal Kenya. We compared their responses to uncomplicated childhood fevers reported in the two weeks preceding the surveys. Despite dramatic demographic differences between the rural and urban study populations (Molyneux et al. 1999a), in access to formal and informal biomedical services (Tables 1 and 2), and in the samples’ characteristics, responses to uncomplicated fevers were similar (Tables 4 and 5). One key finding is the importance of shop-bought medications as an initial response to the onset of fever in both 842 volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 areas. The frequent and early use of shop-bought antimalarials in household responses to fever/malaria has been shown in numerous rural populations in sub-Saharan Africa (Deming et al. 1989; Barnish et al. 1993; Foster et al. 1993; Yeneneh et al. 1993; Vundule & Mharakurwa 1996). Relatively few studies have compared rural and urban residents’ responses, and where they have, authors have noted both striking differences and great similarity in use of shopbought drugs (Glik et al. 1989; Makubalo 1991; Mwenesi 1993; Kilian 1995). Nevertheless, all studies of urban populations have shown that the purchasing of shop-bought drugs constitutes over 40% actions taken, in most cases as a firstline response (Glik et al. 1989; Makubalo 1991; Carme et al. 1992; Mwenesi 1993; Kilian 1995; Chiguzo 1999). As in rural areas, the attraction of shop-bought drugs in urban areas is ‘rational’: there are numerous shops offering a cheap and convenient service relative to even nearby government and private facilities; and drugs are readily available and in many cases cure or alleviate the patient’s symptoms (Molyneux 1999). We did not document drugs purchased from shops, or dosages administered to children. Researchers in the rural study area have shown, however, that drugs are generally administered ‘with little information on correct use, leading to random choices of drugs [being] used on a trial and error basis, with rapid alterations in treatment if no immediate improvement is seen, and no concept of a need to continue treatment in the absence of symptoms’ (Marsh 1998). In low-income settlements of Mombasa, only 16–39% of mothers know the correct chloroquine dose for a three-yearold (Government of Kenya 1992), and the inappropriate administration of antimalarials has been noted in other urban areas (Stein et al. 1988; Makubalo 1991; Lipowsky et al. 1992; Massele et al. 1993; Chiguzo 1999). Greater access to second-line antimalarials from informal vendors (as we demonstrated in this paper), and the ease in some areas of obtaining drugs from pharmacies without prescription (Indalo 1997), may be a source of particular concern in urban areas, with important implications for the regulation of prescription-only antimalarial drugs. However, given that chloroquine resistance is widespread in Kenya, the urban informal sector may be responding to a high clinical demand for second-line drugs. The very recent shift from chloroquine to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine as Kenya’s first-line antimalarial suggests that national policy-makers have recognized and are responding to this demand. The way in which this policy change will translate into practice, and the subsequent implications of this shift, remain unclear. We noted that the only significant difference in rural and © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 C. S. Molyneux et al. Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya urban mothers’ reported responses was in the use of private/ government clinics: rural mothers were more likely to seek government services, and urban mothers to consult private practitioners. Informal discussions suggested greater use of private practitioners by urban resident mothers was due to a number of factors including the relative proximity and quality of care offered at these facilities; the cost in time, money and (in some cases) work lost incurred in attending a government facility; and more immediate access than in rural areas to cash from work, a husband, or a neighbour (Molyneux 1999; Molyneux et al. 1999b). A number of study-specific factors may have biased our findings, including recall period and the position of the rural study area. Regarding recall period, mothers in both study areas reported that healers are generally contacted if biomedical practitioners ‘fail’ to cure a fever (Molyneux et al. 1999b). Switch in form of therapy has been noted elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa as a response to severe, chronic and recurring illnesses (Good 1987). In malaria, this may include what biomedical practitioners would term re-infections, relapses and recurrence of symptoms (Hausmann Muela et al. 1998). Larger sample sizes or a longer recall period may therefore have revealed a greater proportion of rural mothers visiting healers. Conversely, or in addition, use of biocultural therapy may have been under-reported in the rural area. Nevertheless, in both areas mothers openly reported far greater use of herbs and healers in response to childhood convulsions (Molyneux et al. 1999b), suggesting such biases were minimized. Regarding the position of the rural study area, proximity to Kilifi town ensures the population relatively good access to the town’s health facilities. This includes high-quality care provided in the Wellcome-KEMRI research wards at Kilifi District Hospital. Study area mothers may therefore use biomedicine more often and more promptly than would be the case in the more interior areas of Kilifi District. Although this could be considered particularly problematic in a rural-urban comparison, the differences between the rural and urban study populations in demography and in access to biomedical services suggest the comparison is valid. This is supported by the documentation of similar treatment-seeking patterns in rural and in urban areas elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. One explanation for the similarity in rural and urban mothers’ treatment-seeking patterns may be the exchange of ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ information and ideas about different illnesses and appropriate therapy. In coastal Kenya such exchanges are the inevitable outcome of chain rural-urban migration, the maintenance of rural-urban ties, high mobility between rural and urban populations, and return migration. These demographic features have been observed all over subSaharan Africa (Todd 1996). However, perhaps a more important explanation is related to the high use of shop- © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd bought antimalarials in both areas. In a context of growing intra-urban inequity in access to services, an increasing proportion of urban residents living in absolute poverty, the introduction of user-fees, and deteriorating quality of care in government facilities, the attraction of shops in providing a relatively low-cost, convenient and reliable (in terms of drug availability) service cannot be overstated. The enormous potential there is to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality through the improvement of home treatment of childhood fevers has led to a number of community-based initiatives, including the training of mothers, community health workers, or shop-keepers in diagnosis, appropriate antimalarial use, and referral (Spencer et al. 1987; Greenwood et al. 1988; Delacollette et al. 1996; Pagnoni et al. 1997; Marsh et al. 1999). These initiatives have largely taken place in rural areas, and have demonstrated changes in treatment-seeking practice and, less frequently, reductions in morbidity. Although the data presented in this paper shows that such community-based interventions are at least as relevant for low-income urban populations, a number of efficiency and equity issues arise from rural-urban differences in socioeconomic, cultural and demographic factors, and health facility organization and accessibility. Should time and resources be channelled into improving socio-economic access to and drug availability in existing services as opposed to developing new interventions? Would this have any impact on the use of shop-bought medicines? Which interventions would have the greatest impact on reducing mortality? To what extent do high mobility, the breakdown of traditional family structures, changing gender relations and the ethnic and socio-cultural diversity prevalent in most cities (Silimperi 1994) affect community-based initiatives, and indeed the development of an urban ‘community’ identity? The popularity of self-medication all over the world suggests the use of over-the-counter drugs will remain a norm in household treatment-seeking. However, there is still much to learn about reasons for and the appropriateness of drug use in sub-Saharan African towns. Clearly, research and interventions aimed at reducing urban morbidity and mortality will have to consider multiple and competing health providers, as well as the perspectives of a diverse range of community members. This may become increasingly feasible with the recent shift in approaches to urban health from ‘topdown’ disease-targeted projects to ‘bottom-up’, processorientated programmes aimed at improving the overall well-being of urban citizens. Acknowledgements This research was funded by The Wellcome Trust, UK (Grant number 033340) and the Kenyan Medical Research Institute. 843 Tropical Medicine and International Health C. S. Molyneux et al. Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya We wish to thank Dr Norbert Peshu and Professor Kevin Marsh for their support and Dr Vicki Marsh her useful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the fieldworkers, data entry clerks and administrative staff at the KEMRI Unit for their hard work and dedication, and special thanks to the rural and urban study area residents whose assistance and cooperation made the study possible. RWS is supported by The Wellcome Trust as part of their senior fellowships programme in Basic Biomedical Sciences. This paper is published with the permission of the director of KEMRI. References Bambrah CK (1996) Draft Proceedings of the Municipal Consultation on Urban Poverty Reduction. 10th-12th April, Polana Hotel, Mombasa District. Barnish G, Maude GH, Bockarie MJ, Eggelte TA, Greenwood BM & Ceesay S (1993) Malaria in a rural area of Sierra Leone. 1. Initial results. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 87, 125–136. Brockerhoff M & Brennan P (1998) The poverty of cities in developing regions. Population and Development Review 24, 75–114. Carme B, Koulengana P, Nzambe A & Du Bodan G (1992) Current practices for the prevention and treatment of malaria in children and in pregnant women in the Brazzaville region (Congo). Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 86, 319–322. Chant S & Radcliffe AS (1992) Gender and Migration in Developing Countries. Belhaven Press, London. Chiguzo AN (1999) Factors associated with the occurrence of malaria epidemics. The case of Hurumasa peri-urban, Eldoret Municipality, Kenya. Poster presented at the MIM African Malaria Conference. 14–19 March, Durban, South Africa. Cunningham-Burley S (1990) Mothers’ beliefs about and perceptions of their children’s illness. In Readings in Medical Sociology (eds S Cunningham-Burley & N McKeganey). Routledge, London. Delacollette C, Van der Stuyft P & Molima K (1996) Using community health workers for malaria control: experience in Zaire. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 74, 423–430. Deming M, Gayibor A, Murphy K, Jones T & Karsa T (1989) Home treatment of febrile children with antimalarial drugs in Togo. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 67, 695–700. Foster SO, Spiegel RA, Mokdad A et al. (1993) Immunization, oral rehydration therapy and malaria chemotherapy among children under five in Bomi and Grand Cape Mount Countries, Liberia 1984 and 1988. International Journal of Epidemiology 22 (Suppl.), S50–S55. Glik D, Ward W, Gordon A & Haba F (1989) Malaria treatment practices among mothers in Guinea. Journal of Heath and Social Behaviour 30, 421–435. Government of Kenya (1990) Mombasa District Development Plan 1989–93. Ministry of Planning and National Development, Government Printers, Nairobi. Government of Kenya (1992) Baseline survey information for Kongowea, Freretown/Kisauni, Likoni and Chaani sites. Unpublished report by the Mombasa Municipal Council Bamako Initiative Programme, Mombasa. 844 volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 Gould STW (1998) African mortality and the new ‘urban penalty’. Health and Place 4, 171–181. Greenwood BM, Bradley AK, Greenwood AM et al. (1988) Comparison of two strategies for control of malaria within a primary health care programme in the Gambia. Lancet i, 1121–1127. Good CM (1987) Ethnomedical systems in Africa. Patterns of Traditional Medicine in Rural and Urban Kenya. Guilford Press, New York. Harpham T (1997) Urbanisation and health in transition. Lancet 349, 11–13. Hausmann Muela S, Muela Ribera J & Tanner M (1998) Fake malaria and hidden parasites – the ambiguity of malaria. Anthropology and Medicine 5, 43–61. Indalo AA (1997) Antibiotic sale behaviour in Nairobi: a contributing factor to the antimicrobial drug resistance. East African Medical Journal 74, 171–173. Kilian AHD (1995) Malaria control in Kabarole and Bundibugyo Districts, Western Uganda. Report on a comprehensive malaria situation analysis and design of a district control programme. 14–15 March 1995, Fort Portal, Uganda. Kindy H (1972) Life and Politics in Mombasa. East African Publishing House, Nairobi. Kleinman A (1980) Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. University of California Press, Berkeley. Kloos H, Etea A & Degefa A (1987) Illness and health behaviour in Addis Ababa and rural Central Ethiopia. Social Science and Medicine 25, 1003–1019. Lipowsky R, Kroeger A & Vazquez ML (1992) Sociomedical aspects of malaria control in Columbia. Social Science and Medicine 34, 625–637. Makubalo EL (1991) Malaria and chloroquine use in Northern Zambia. PhD Thesis, LSHTM, University of London. Malombe JM & Kanyonyo M (1997) Urban community appraisal and planning in Nairobi: a review of experience. Unpublished report prepared for the British Development Division in Eastern Africa, Nairobi. Marsh V (1998) Implementation and evaluation of a shop keeper training programme to optimise the home use of shop-bought antimalarial drugs for uncomplicated childhood fevers in coastal Kenya. DFID Grant Proposal R7179 (RD493). Marsh VM, Mutemi WM, Muturi J et al. (1999) Changing home treatment of childhood fevers by training shop keepers in rural Kenya. Tropical Medicine and International Health 4, 383–389. Massele YA, Sayi J, Nsimba DES, Ofori-Adjeyi D & Laing OR (1993) Knowledge and management of malaria in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. East Africa Medical Journal 70, 639–641. Mazrui AA (1996) Mombasa: three stages towards globalisation. In Re-Presenting the City: Ethnicity, Capital and Culture in the Twenty-First Century Metropolis (ed. AD King). New York University Press, New York. Mburu FM, Spencer HC & Kasesje DCO (1987) Changes in sources of treatment occurring after inception of a community-based malaria control programme in Saradidi, Kenya. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 81 (Suppl. 1), S105–S110. Molyneux CS (1999) Migration, mobility and health-seeking behaviour of mothers living in rural and peri-urban areas on the Kenyan Coast. PhD Thesis, South Bank University, London. © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 4 no 12 pp 836–845 december 1999 C. S. Molyneux et al. Maternal responses to childhood fevers in Kenya Molyneux CS, Mung’ala-Odera V, Harpham T & Snow RW (1999a) Migration and circulation among low-income mothers on the Kenyan Coast: implications for health policy. Submitted to Health Policy and Planning. Molyneux CS, Murira G, Masha J & Snow RW (1999b) Intra-household relations and treatment decision making for child illness: a Kenyan case study. Submitted to Social Science and Medicine. Mwenesi H (1993) Mothers’ Definition and treatment of childhood malaria on the Kenyan Coast. PhD Thesis, LSHTM, University of London. Pagnoni F, Convelbo N, Tiendrebeogo J, Simon C & Esposit F (1997) A community based programme to provide prompt and adequate treatment of presumptive malaria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 91, 512–517. Parkin JD (1979) Along the line of road expanding rural centres in Kenya’s coast province. Africa 49, 273–282. Parkin D (1991) Sacred void. Spatial Images of Work and Ritual Among the Giriama of Kenya. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Parry C (1995) Quantitative measurement of mental health problems in urban areas: opportunities and constraints. In Urbanisation and Mental Health in Developing Countries (eds T Harpham & I Blue), Aldershot, Avebury. Silimperi D (1994) Delivering child survival services to high risk populations (draft), BASICS Strategy Paper. pp 1–57. Snow RW, Mung’ala VO, Foster D & Marsh K (1994) The role of the © 1999 Blackwell Science Ltd district hospital in child survival at the Kenyan Coast. African Journal of Health Sciences 1, 71–75. Spencer HC, Kaseje DCO, Mosley WH, Sempebwa EKN, Huong AY & Roberts JM (1987) Impact on mortality and fertility of a community-based malaria control programmes in Saradidi. Kenya. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 81 (Suppl.), S36–S45. Stein CM, Gora NP & Macheka BM (1988) Self medication with chloroquine for malaria prophylaxis in urban and rural Zimbabwians. Tropical and Geographical Medicine 40, 264–268. Stock R (1985) Health care for some: a Nigerian study of who gets what, where and why? International Journal of Health Services 15, 469–483. Tanner M & Harpham T (1995) Action and research in urban health development – progress and prospects. In Urban Health in Developing Countries: Progress and Prospects (eds T Harpham & M Tanner). Earthscan Publications Ltd, London, pp. 216–220. Todd A (1996) Health inequalities in urban areas: a guide to the literature. Environment and Urbanisation 8, 141–152. Vundule C & Mharakurwa S (1996) Knowledge, practices, and perceptions about malaria in rural communities of Zimbabwe: Relevance to malaria control. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 74, 55–60. Yeneneh H, Gyorkos TW, Joseph L, Pickering J & Tedla S (1993) Antimalarial drug utilization in women in Ethiopia, results from a KAP study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 71, 763–772. 845

© Copyright 2026