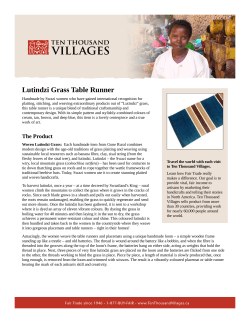

HOW TO PROMOTE THE ROLE OF YOUTH NOTE