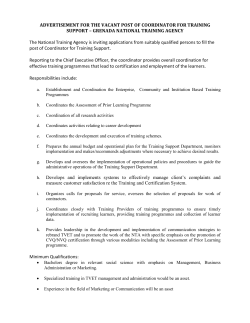

Where Next for Social Protection? - Institute of Development Studies