Field of study variation throughout the college pipeline and its effect

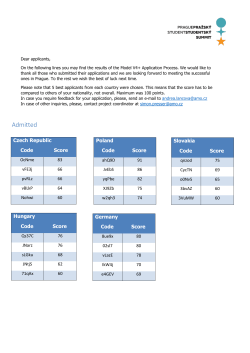

Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Social Science Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ssresearch Field of study variation throughout the college pipeline and its effect on the earnings gap: Differences between ethnic and immigrant groups in Israel Sigal Alon ⇑ Tel-Aviv University, Israel a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 27 January 2014 Revised 19 February 2015 Accepted 19 March 2015 Available online 28 March 2015 Keywords: Field of study Undermatching College pipeline Earnings gap Ethnic inequality Israel a b s t r a c t This study demonstrates the analytical leverage gained from considering the entire college pipeline—including the application, admission and graduation stages—in examining the economic position of various groups upon labor market entry. The findings, based on data from three elite universities in Israel, reveal that the process that shapes economic inequality between different ethnic and immigrant groups is not necessarily cumulative. Field of study stratification does not expand systematically from stage to stage and the position of groups on the field of study hierarchy at each stage is not entirely explained by academic preparation. Differential selection and attrition processes, as well as ambition and aspirations, also shape the position of ethnic groups in the earnings hierarchy and generate a non-cumulative pattern. These findings suggest that a cross-sectional assessment of field of study inequality at the graduation stage can generate misleading conclusions about group-based economic inequality among workers with a bachelor’s degree. Ó 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction In most Western countries, participation in all levels of the education system has been increasing for decades, as has the overall level of academic credentials. Yet there is a mismatch in many countries between the decline in racial/ethnic and gender gaps in educational attainment, and the persistence of earnings gaps. This is possible partly because high-status groups are able to secure an education that, although quantitatively similar in terms of years of schooling, is qualitatively superior—either by type of institution or field of study—which, in turn, leads to better economic returns (Alon, 2009; Lucas, 2001). Recent evidence suggests that college major is the most important determinant of future earnings, even after controlling for ability (Arcidiacono, 2004; Roksa and Levey, 2010). In fact, the disparity in returns across college majors rivals the college wage premium (Altonji et al., 2012).1 Consequently field of study variation accounts for much of the racial/ethnic and gender gaps in starting salaries among college graduates ⇑ Address: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel. E-mail address: [email protected] Altonji et al. (2012) find that the gap in wage rates between male electrical engineering and general education majors is as large as the gap between college and high school graduates. 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.03.007 0049-089X/Ó 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 466 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 (Rumberger and Thomas, 1993; Weinberger, 1998). The potential of using field of study variation to explain economic inequality is thus considerable. Field of study inequality can be observed throughout the college pipeline, especially in the application, admission and graduation stages. Variation in occupational and field of study aspirations exists among high school students due to disparities in economic resources, K-12 academic preparation, knowledge about college majors and occupations, and ambition and maturity (Schneider, 2009). In countries where applicants are asked to ranked their field of study preferences at the application stage—such as in Israel, Australia and most European countries—it is possible to study the variation in college major choice set, even before college entry, as prospective applicants must list their preferred majors and rank them accordingly. Hällsten (2010), for example, finds that college applicants in Sweden from service class backgrounds are more likely to choose majors with high potential earnings than those from manual labor class backgrounds. Other studies concur that social background affects the choice of field of study, although the direction of the effect is not clear (see, for example, Reimer and Pollak (2005) on Germany and Van de Werfhorst et al. (2001) on the Netherlands). In such settings, where the application and admission stages are major-specific, the admissions decision, which determines field of study, can contract or expand group inequality. Even in countries where college applicants do not generally choose a major at the application stage, as in the U.S., preferences regarding fields of study (and future occupations) shape applicants’ decisions about educational attainment (Altonji et al., 2012; Schneider and Stevenson, 1999). However, field of study preferences cannot be observed directly at the application stage in these settings—rather, the only information that surveys and college administrative data provide is regarding ‘‘intent to major’’ and ‘‘declared major.’’ As a result, the research in the U.S. tends to focus on inequality in applicants’ choice set of colleges, not majors or fields of study. For example, several studies have focused on the phenomenon of college undermatching—that is, when a high school graduate attends a college that is less selective than what her academic achievement indicates—which tends to be more widespread among minority and low-SES students (Bowen et al., 2009; Hoxby and Avery, 2012). At the same time, we know little about field of study matching, and about whether there are class, gender, or ethnic differences in the fields of study that students consider, either before or after enrollment in college. But the effect of field of study on the formation of economic inequality does not end after enrollment in a major (whether upon admission or later in college). Fields of study vary in their grading norms, curricular structures, and social and academic climates, all of which affect persistence (Alon and Gelbgiser, 2011; Des Jardins et al., 2002; Hearn and Olzak, 1981; Leppel, 2001; Xie and Shauman, 2003). For example, stricter and more competitive academic climates, which are typically associated with lucrative occupations, can result in higher dropout rates.2 Moreover, competitive environments and a lack of diversity can inhibit the academic performance of students who are minorities in these fields by exacerbating both the pressure to perform well, and the fear of confirming stereotypes that they will not perform well, a process known as ‘‘stereotype threat’’ (Jayanti and Lynch, 2012; Steele and Aronson, 1995; Steele, 1997).3 Some students change majors or drop out of college altogether, both of which contribute to the emergence of group differences in fields of study among graduates. If the dropout patterns in majors vary by ethnicity, gender or class, then the predictions regarding group economic inequality will morph from enrollment to graduation. Although field of study inequality tends to transform throughout the stages of the college pipeline, there is no study that tracks this process—from the applicant’s major choice set to the type of degree attained—and that quantifies its implications for economic inequality. There are studies that examine inequality in the diploma type of graduates upon entering the labor market, but these studies overlook the impact of earlier stages in the college pipeline on this outcome (e.g., Carnevale et al., 2011). Alternatively, there are studies that demonstrate group differences in the field of study choice sets of applicants, but they do not track how field of study-related economic inequality changes from the choice stage to degree attainment (e.g., Hällsten, 2010). Finally, there are studies that assess the transformation in fields of study by group after enrollment, either due to dropping out or transferring, but the declared major is the typical starting point, rather than the fields in the major choice set (e.g., Alon and Gelbgiser, 2011; Arcidiacono et al., 2012; Riegle-Crumb and King, 2010). In this study, I combine the various pieces of the puzzle regarding the formation of ethnic-based field of study inequality, from application through graduation. I use universities’ administrative data regarding the major choice sets of applicants (a ranked list of preferences), the admissions decisions of the universities, and the type of diplomas that graduates attain. The Israeli university setting is especially conducive for assessing field of study inequality throughout the college pipeline because Israeli applicants apply to specific majors (including those that lead to most professional degrees) and departments within colleges and universities, so that both the application and admission stages are major specific. Another advantage is the ability to quantify the economic consequences of field of study inequality. I use data on the monthly salary that a graduate in a certain field can anticipate upon labor market entry from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, which draws from the administrative records of the state tax authorities. Moreover, because the bachelor’s admissions process is formulaic (based entirely on a composite academic score), the current study can fully replicate each applicant’s major-specific admissibility, and net out the effect of prior academic credentials on group variation by field of study. This unique setting 2 For example, the strict and competitive academic climates in STEM fields can result in higher dropout rates (DiPrete and Buchmann, 2013; Hearn and Olzak, 1981; Suresh, 2006; Xie and Shauman, 2003). 3 The lack of diversity among professors and role models may generate an environment in which students who are underrepresented in these departments— females, ethnic minorities, and the socioeconomically underprivileged—find it harder to flourish (Fisher and Margolis, 2002; Hearn and Olzak, 1981; Margolis et al., 2008; Price, 2010; Xie and Shauman, 2003). S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 467 enables me to assess whether field of study variation throughout the college pipeline contributes to the persistent economic inequality between ethnic and immigrant groups in Israel. Moreover, this analytical framework allows me to link the ethnicity-based variation among graduates to differences to academic preparation, field of study aspirations (which can lead to either undermatching or overmatching), and/or to group differences in college performance. The insights gained from this investigation are used to develop general inferences about the formation of field of study-related economic inequality. 2. The economic and educational gaps in Israeli society The Israeli population is divided along ethnic lines. The first cleavage is between Israeli Jews, who account for approximately 80 percent of the population, and Israeli Arabs, who make up the rest. This investigation focuses on the Jewish population because Arabs have distinct patterns of participation in both the higher education system and the labor market.4 The Jewish population in Israel is divided along ethnic lines: ‘‘Ashkenazi,’’ those of European and/or American origin, and ‘‘Mizrachi,’’ those with roots in Asia and/or Africa. Before 1948, there were several immigration waves to Israel from both America and Europe, with the first major wave starting in 1882.5 The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 brought with it massive waves of Jewish immigrants, who continued to arrive throughout the 1950s. These waves consisted mainly of refugees from Europe, on the one hand, and those from Asia and Africa, on the other. In the early 1990s, there was another massive immigration wave, dominated by immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU).6 They consist of about 15 percent of the Jewish population. The social and cultural assimilation of the European and American immigrants in Israeli society was smoother, in general, than that of the immigrants from Asia and Africa. Consequently, an earnings hierarchy was institutionalized among the Jewish population of Israel, one in which the Ashkenazi Jews are at the top of the socioeconomic ladder, the Mizrachi Jews are at the bottom, and Jews of mixed ethnicity occupy the space in the middle (Cohen et al., 2007; Dahan et al., 2002; Yaish, 2001). Within each category, second- and third-generation immigrants rank higher than the first generation, and the ethnic earnings gaps are smaller among women than among men. The economic differential between Ashkenazi and Mizrachi Jews has largely been attributed to the gaps in educational attainment between these groups. Recent studies indicate a gradual convergence in the ethnicity-based educational attainment gap in Israel over time, as measured mainly by mean years of schooling and the share of group members holding a bachelor’s degree (Friedlander et al., 2002; Haberfeld and Cohen, 2007; Okun and Friedlander, 2005). Yet, the ethnic gaps in annual earnings among male bachelor’s degree holders in Israel widened (Cohen and Haberfeld, 1998; Haberfeld and Cohen, 2007). For example, while the ratio of the percentage of native-born Mizrachi men with a bachelor’s degree to their Ashkenazi counterparts climbed steeply between 1992 and 2001 (from .25 to .45), the respective ratio of monthly earnings rose only slightly, from .64 to .68 (Haberfeld and Cohen, 2007). Moreover, an ethnicity-based gap in earnings exists even among the younger cohorts of the college-educated population. In analyzing several Israeli Income Surveys, I found that, between 2005 and 2008, second-generation Mizrachi men between the ages of 27 and 29 who had attended an institution of higher education earned a monthly salary that was 83 percent that of second-generation Ashkenazi men in the same age cohort. During the same period, Mizrachi women of the same age cohort earned 94 percent of what their Ashkenazi peers earned. Foreign-born men who immigrated to Israel from the FSU enjoyed the highest pecuniary returns (106 percent that of Ashkenazi men), while the salary of male immigrants from other parts of the world was only 83 percent that of Ashkenazi men. This pattern of mismatch between educational attainment and earnings is not unique to Israel. For example, in the US the gap in earnings determinants, such as education, between black and white women has been on the decline since the early 1980s. At the same time, the gap in earnings between these two groups has persisted (Altonji and Blank, 1999; Blau and Beller, 1992). In addition to the possibility of rising discrimination, several other theories have been offered to explain this paradox. One of them, put forward by Juhn et al. (1991), posits that education quality is a key factor in the slowdown of the black–white wage convergence.7 Following this logic, Cohen et al. (2007) speculate that group-based differences in the quality of education, such as differences in institution type and/or field of study, may be one of the reasons that the ethnicity-based gaps in earnings persist in Israel. As of 2013, the higher education system in Israel is made up of about 70 postsecondary institutions that can be grouped into two tiers. In the first tier, there are six research universities. In the second tier, there are many new non-selective degree-granting academic colleges, which are largely the product of the massive expansion of the Israeli higher education system that began in 1995.8 In both tiers applicants apply to specific majors within each institution. Given that youth of 4 As a result of geographical segregation, labor market structure, differences in human capital, traditions and discrimination, Arabs have higher unemployment rates than Jews. Those who work are concentrated in a few industrial sectors and occupations and earn less than their Jewish counterparts (Yashiv and Kasir, 2009). Because of these restricted labor market opportunities, Arab students tend to be concentrated in a few fields of study. In 2006, for example, Arabs accounted for about eight percent of degrees that the first-tier universities awarded overall, but for about 20 percent of the degrees awarded in medicine and 20 percent of the degrees awarded in paramedical studies. In contrast, they received only four percent of the degrees awarded in engineering. 5 The majority came from the Russian Empire, with smaller numbers arriving from countries in the Middle East, such as Syria and Yemen. 6 There were also two small waves of immigration from Ethiopia during this period. 7 They found that between 1979 and 1987, almost the entire wage gap between racial groups at the same education levels was attributable to differences in education quality. 8 Between 1994/95 and 2010/11, the total number of undergraduate students more than doubled, from 86,000 to 183,000. This was mostly due to the addition of second-tier institutions (although the number of undergraduate students attending the six universities also increased). 468 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Mizrachi origin are more likely than their Ashkenazi counterparts to attend the second-tier non-research colleges, the expansion of the higher education system has helped narrow the gap in bachelor’s degree attainment (Ayalon, 2008). That said, because the economic returns on degrees from second-tier colleges are lower than the returns on degrees from the major universities (Suzzman et al., 2007), the ethnic wage gap persists. Furthermore, within the first-tier universities, Mizrachi Jews are under-represented in highly selective fields. For example, in 2006/07, Mizrachi university graduates were over-represented in the humanities and social sciences, but under-represented in (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS), 2009). This study examines the proposition that the ethnic variation in majors may explain the ethnicity-based gaps in earnings, even among the younger cohorts of the college-educated population. The empirical investigation tracks the variation in field of study among different ethnic origin groups in Israel, quantifies the economic implications of this process in terms of expected salary, and considers several factors that may account for the variation in fields of study. 3. Data and methods 3.1. Database The empirical investigation utilizes the institutional administrative records of the three largest first-tier Israeli universities—Tel Aviv University (TAU), The Hebrew University (HUJI), and Ben-Gurion University (BGU) (see Alon (2011) for details). Due to the over-time changes in the demographic composition of the college-age population, as described below, I limit the analyses to the applicant cohorts from 1999 to 2002. During this period, these three universities received 90,000 applications. About 63,000 applicants were admitted and 45,000 students eventually enrolled. Seventy-three percent of the latter graduated from one of these three universities. 3.2. Variables 3.2.1. Ethnic origin The conventional classification scheme for ethnicity among the Jewish population in Israel, used in previous research and official statistics, is based on either continent of birth or father’s continent of birth, using the dichotomy of Asia/Africa (Mizrachi) and Europe/America (Ashkenazi).9 However, because this scheme recognizes only first- and second-generation immigrants, and ignores the possibility of mixed ethnicity, it is inadequate for describing the contemporary college-age population, which, as time lapses from the major immigration waves of the late 1940s and 1950s, is increasingly comprised of third-generation Jews—that is, native-born Israeli Jews whose parents were also born in Israel.10 Among individuals who applied to the three universities between 1999 and 2008 the pattern is clear: the share of third-generation applicants (native-born Israeli Jews with two native-born parents) is surging. In 1999, about 54 percent of the applicant pool to university was third generation; by 2008, this share was 69 percent.11 Given this trend, and in order to keep the share of the third-generation group—whose exact ethnicity is impossible to discern—as small as possible, this analysis is limited to the older cohorts in the sample, those who applied between 1999 and 2002. This also ensures that each ethnic origin category is more homogeneous in terms of time of immigration to Israel, and allows for a longer observation window through which to follow the applicants until graduation. As mentioned above, the other problem with the conventional classification of ethnicity is that it does not reliably reflect individuals of mixed ethnicity and mixed generations, because it ignores the ethnicity and generation of the mother.12 Given the rise in ethnic intermarriage, this is a growing population, especially among the native born (Okun and Khait-Marelly, 2008; Gshur and Okun, 2003; Okun, 2004). Fortunately, the university administrative data has information about the ethnic origin of both parents of applicants. Thus, I created a measure for ethnic origin that takes into account both mixed-ethnicity status and immigrant generation, which is presented in Table 1. Thirty-three percent of applicants between 1999 and 2002 were third generation on both sides and thus their ethnicity cannot be classified. Yet, this classification distinguishes between applicants who are ‘‘veteran’’ Ashkenazi (those who are third-generation on one side and second-generation from Europe/America on the other) and second-generation Ashkenazi (individuals whose parents both immigrated from Europe or America). Likewise, Mizrachi applicants, those with roots in Asia/Africa, are classified as veteran Mizrachi or second-generation Mizrachi. Twenty percent of the applicant body were first-generation Jewish immigrants, the majority of which was part of the massive immigration wave from the FSU that began in the early 1990s, while about a quarter of the first-generation pool from non-FSU countries came from the US. 9 This scheme distinguishes between native-born Israeli Jews with a native-born father; native-born Israeli Jews with a father born in Asia or Africa; nativeborn Israeli Jews with a father born in Europe or America; immigrants from Asia or Africa; and immigrants from Europe or America. 10 Today, almost 40 percent of the age cohort of potential university applicants is third-generation Jews (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS), 2010). 11 At the same time, the share of second-generation applicants (native-born Israeli Jews with one or both parents born outside of Israel) declined from 25 to 12 percent. Due to immigration from the former Soviet Union throughout the 1990s, the share of first-generation immigrant applicants remained stable at approximately one-fifth. 12 For example, individuals classified as third generation (native-born Israeli Jews with a native-born father) could have a mother who is either third or second generation. Moreover, the mother could be a native-born Israeli, from Asia/Africa, or from Europe/America. 469 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Table 1 A classification of ethnic origin of the Israeli universities applicant pool, 1999–2002. Origin group Generation Applicants 1999–2002 (%) Two native-born parents One native-born parent and one from Asia or Africa (veteran ‘‘Mizrachi’’) One native-born parent and one from Europe or America (veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) Both parents from Asia or Africa (2nd generation ‘‘Mizrachi’’) Both parents from Europe or America (2nd generation ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) One parent from Europe or America and one from Asia or Africa (mix ethnicity) Immigrants from Former Soviet Union (FSU) countries Immigrants from other countries 3rd 2nd–3rd 2nd–3rd 2nd 2nd 2nd 1st 1st 33.2 9.5 13.8 10.6 9.1 3.2 13.7 6.9 3.2.2. Field of study economic hierarchy To quantify the economic consequences of field of study inequality by ethnic origin, I use data from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, which draws from the administrative records of the state tax authorities. Specifically, I use the monthly salary of university graduates during their first years in the labor market following graduation, by field of study and by institution (ICBS, 2012).13 Altogether, there was institution-specific data on expected earnings for 39 fields of study. The data was obtained for four cohorts of university graduates, from 2000 through 2003, during their first two years in the labor market, separately for men and women.14 I merged this information on field of study expected salary with the data, assigning each applicant, admit, and graduate the corresponding projected salary by his or her field of study at each stage. In the case of double majors, the salary assigned was that of the major with the highest salary (at each stage).15 In sum, each woman in the sample was assigned, at each stage—application, admission, enrollment and graduation—the average monthly salary of female graduates in her corresponding field and institution. Similarly, each male was assigned, at each stage, the salary of male graduates in his field/institution. This measure of field of study expected salary is appropriate for the research question at hand because, of all types of wage data, it is closest to the actual information that applicants/students have before/during college (Hällsten, 2010; Wiswall and Zafar, 2013). That is, applicants/students do not know how much they will earn after labor market entry. At best, they may know the average salary among recent graduates in certain fields (Manski, 1983). The current analysis exposes group differences that can be attributed to between-major variance in earnings. If there are differences in labor market treatment or preferences between ethnic groups within each major exist, then the gaps revealed in this study are an underestimation of the actual gaps between the groups.16 The expected salary ranges from 5000 to 20,000 New Israeli Shekels (NIS), for the graduates of three universities who began their studies between 1999 and 2002 (see Table 2).17 There are substantial gaps in economic value in the labor market between fields of study. Leading the pack in terms of starting monthly salary are the graduates of various engineering programs, the computer sciences, exact sciences, pharmaceutical studies and economics.18 At the bottom are the graduates of several fields in the humanities and social sciences. There is a sizable gender divide: the potential starting salary, on average, of males with bachelor’s degrees is more than 11,000 NIS, while that of their female counterparts is about 7000 NIS. This is not just the result of field of study variation between men and women, but also of the gender gap within fields: that is, the salary of male graduates is higher than that of females, even when their diplomas are in the same field and from the same institution. The analyses of the ethnic differences in this study are conducted separately for men and women using their corresponding earnings data. 3.2.3. Academic score This score is calculated by taking a weighted mean of an individual’s matriculation diploma grades (similar to AP grades) and psychometric test score (similar to an SAT score). I standardized the score for each institution so that each applicant is ranked relative to the academic score of the relevant institution’s applicant pool (an institution-specific percentile distribution). 13 I divided the annual earnings by the number of months that the graduates in each field of study were employed, in order to adjust for differences in labor supply. 14 Graduates who pursued advanced degrees were omitted, as were those younger than 21 or older than 35 years of age. 15 Students and graduates can have a double major, and applicants can include more than one major in their major choice set. 16 The salary reflects not only the value of the field of study, but also factors such as sector, industry, geographic location, preferences, employability, unobserved characteristics and discrimination. To be sure, all these aspects are captured in the average field of study expected salary, but they do not interfere with the assessment of the divide in potential earnings because graduates of all origins are assigned the same figure. 17 The NIS are in 2004 prices, and the salary of graduates from corresponding departments across all three institutions was averaged. This is only for the purpose of Table 2. All the analyses are based on the major-institution-specific data. 18 I deleted applicants to medicine and dentistry from the sample. The wage data reported for these fields is inaccurate because, due to the length of study of these fields, these students had not yet obtained their professional licenses by the time the data was gathered from the tax authorities. 470 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Table 2 The expected salary by field of study of graduates (NIS in 2004 prices), 1999–2002, average across all three institutions. Major Males Mean Females Mean Electrical Engineering Computer Sciences Industrial & Management Engineering Mathematics Physics Chemical Engineering Mechanical Engineering Engineering – other Law Physiotherapy & Occupational Therapy General Studies [Social Sciences] Political sciences & International relations Nursing Economics Statistics Pharmacy Bio-Medical Engineering Management Communication History & Philosophy Architecture Chemistry Geography Accounting Nutrition sciences Sociology Art Psychology Agricultural sciences Social work Geology Regional studies & foreign languages Medical Laboratory Sciences Education Biology Jewish studies Hebrew, Linguistics & Literature Communication Disabilities General Studies [humanities] Mean 19,187 16,695 14,371 12,913 12,526 12,109 11,804 11,788 10,988 10,760 10,469 10,265 10,181 10,085 10,082 10,032 9243 9237 9006 8936 7576 7565 7535 7478 7438 7416 7315 7097 6984 6973 6844 6835 6545 6326 6056 5598 5468 – – 11,633 17,169 14,992 12,937 10,415 8094 10,689 10,734 9087 8394 6006 6277 6618 7884 8150 7693 8475 8178 7207 6348 6652 5750 6380 5620 6417 4833 5969 5326 4900 5571 5632 5478 5428 4891 5019 5407 4797 5323 5348 7825 7024 4. Results 4.1. The ethnic gap in field of study expected salary among university graduates By the time university graduates in Israel enter the labor market, there is already an ethnic gap in earning potential due to variation in the type of diplomas attained. Table 3 (Panel A) presents the expected salary of university graduates based on the value of their degrees, by ethnic origin group. The ethnic gaps, which are strikingly similar among both male and female graduates, reveal a tripartite hierarchy. Leading the pack are graduates who immigrated from the FSU, together with veteran Ashkenazi graduates.19 The middle tier consists of second-generation or third-generation Mizrachi graduates as well as secondgeneration Ashkenazi graduates. The expected monthly salary, by major, of male graduates in these groups is about 95–96 percent that of FSU-born immigrants (94–95 percent for females).20 At the bottom are first-generation male and female immigrants from other (non-FSU) countries: their expected salary, by major, is only 91 percent that of their FSU-born counterparts. These findings demonstrate that the documented ethnic gaps in earnings among employees with a college diploma are partly shaped by field of study variation upon graduation. Both factors—country of origin and immigrant generation—are involved in determining economic hierarchy. Given that earning trajectories often depend on starting wages and vary by occupation, these initial 19 Males from the FSU graduated from fields in which graduates earn, on average, more than 12,000 NIS upon labor market entry (for FSU females the average salary was 7300 NIS). 20 This may be an underestimation of the ethnic gaps in expected salary among university graduates in Israel because the third-generation group may lump together those with the highest and lowest expected salaries. 471 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Table 3 The field of study expected salary of university graduates by ethnic origin group. Group (sorted) Panel A: Graduates Males Immigrants from FSU One native-born parent and one from Europe or America (veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) One parent from Europe or America and one from Asia or Africa (mix ethnicity) Two native-born parents Both parents from Asia or Africa (2nd generation ‘‘Mizrachi’’) One native-born parent and one from Asia or Africa (veteran ‘‘Mizrachi’’) Both parents from Europe or America (2nd generation ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) Immigrants – others Panel B: Applicants Major’s expected salary (males) % from FSU Imm. Major’s expected salary (males) % from FSU Imm. 12,123 11,942 11,667 11,551 11,547 11,531 11,517 10,988 100 99 96 95 95 95 95 91 13,982 13,175 12,951 12,897 12,967 13,076 12,900 12,206 100 94 93 92 93 94 92 87 % from FSU Imm. Major’s expected salary (females) % from FSU Imm. Females Major’s expected salary (females) Immigrants from FSU One native-born parent and one from Europe or America (veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) One native-born parent and one from Asia or Africa (veteran ‘‘Mizrachi’’) Two native-born parents One parent from Europe or America and one from Asia or Africa (mix ethnicity) Both parents from Asia or Africa (2nd generation ‘‘Mizrachi’’) Both parents from Europe or America (2nd generation ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) Immigrants – others 7375 7095 6997 6991 6971 6912 6899 6711 100 96 95 95 95 94 94 91 8435 7907 7915 7808 7799 7795 7752 7491 100 94 94 93 92 92 92 89 Note: based on major-institution specific averages; the most lucrative major for each graduate/applicant. gaps—when university graduates first embark on their labor market careers—can translate into lifelong differences in economic well-being. To better understand how graduates from different ethnic groups ended up in advantaged or disadvantaged positions on the economic hierarchy, the following analyses track the formation of economic stratification throughout the college pipeline from the high school years to college graduation. To help with tracking this inequality, two types of evidence are presented simultaneously: the expected salary of each group at various stages (gross gaps as well as adjusted for academic achievements), and the transition probabilities from high school graduation until the attainment of a bachelor’s degree. 4.2. Application stage: Field of study choice set Applicants to Israeli universities can list several fields of study on their university applications, but must rank them according to preference. How important are economic returns in shaping the field of study choices of applicants? To compare the magnitude of the effects of several characteristics of a major on inclusion in the choice set, I use the McFadden’s choice model, which is intended specifically for individual decisions that are at least partly based on observable attributes (McFadden, 1974).21 In this conditional fixed-effects logit regression, the dependent variable is the most lucrative major listed by each applicant, and the key independent variable is the major’s expected salary.22 The specification compares the magnitude of this effect to the effect of other characteristics of a major: academic rigor (average standardized composite score among admits), percent female (percent of females among enrolled students), and graduation rate (the percent of enrolled students that graduate). All variables are standardized to facilitate the interpretation of the results. Table 4 presents the results for males and females. Although drawing causal inferences from this specification is not straightforward—either because the correlation between some of the attributes of a major (see correlation matrix at the bottom of Table 4) or because of misspecification (omitted characteristics of a major)—it seems that economic returns are a determinant of a major’s desirability for male applicants. An increase of one standard deviation in a major’s expected salary (about 4000 NIS) doubles the likelihood that a major will be chosen by a male applicant (Model 1: exp (.709)); this holds even when all of a major’s characteristics are considered (Model 5). The effect of economic returns on women’s decision making is more subtle (exp (.125) = 1.13; one SD is about 2000 NIS), and not very different from the effects of other characteristics of a major. This is in line with prior evidence that demonstrates that while expected earnings are an essential component in the selection of a college major, women are less influenced by this factor than men are (Alon and DiPrete, 2015; Montmarquette et al., 2002). Male and female applicants may weight factors differently when choosing what to study, but the key question for this study is, within each sex group, are there ethnic differences in the effect of a major’s pecuniary returns, and, if so, what are the economic implications of this disparity? 21 To fit this model, the data were converted into person-major configurations, generating a row for each alternative (39 fields of study) for each applicant (N = 90,000). The analysis is based on 3,348,108 person-major observations. expðzij cÞ 22 ð1Þ Prðyi ¼ jjzi Þ ¼ P j ; j ¼ 0; 1; . . . ; J. j¼1 expðzij cÞ 472 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Table 4 Conditional logit model: the effect of major’s characteristics on major choice (most lucrative major), 1999–2002 applicants. Variables (Standardized) Males Females (1) (2) Major’s expected salary (M/F) 0.709*** (0.00350) Major’s academic rigor (3) 0.533*** (0.00547) 0.788*** (0.00517) Major’s percent females Major’s graduation rate Observations (person-major) 1,380,825 Correlations Matrix 1 1. 2. 3. 4. 1 0.472 0.659 0.2147 Expected salary Academic rigor Female percent Graduation rate 2 1 0.3325 0.4117 3 1 0.156 (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) 0.563*** 0.125*** (0.00687) (0.00396) 0.00296 0.0110* (0.00720) (0.00444) 0.233*** 0.0228*** (0.00832) (0.00443) 0.191*** 0.0251** 0.176*** (0.00567) (0.00771) (0.00479) 1,967,283 0.187*** (0.00666) 0.178*** (0.00575) 0.0244*** (0.00709) 0.231*** (0.00640) 4 1 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 0.4614 0.693 0.1681 1 0.2694 0.4529 1 0.2027 1 Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001. Table 5 The transition probabilities from high school graduation until the attainment of a bachelor’s degree. a b Cohorta Universities applicant poolb 1 HS-PSE 2 Application-Admission 3 Admission-Enrollment 4 Enrollment-Graduation 5 Application-Graduation Males Immigrants from FSU Veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’ Immigrants – others 0.42 0.64 0.53 0.57 0.74 0.68 0.77 0.71 0.72 0.65 0.71 0.64 0.29 0.38 0.32 Females Immigrants from FSU Veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’ Immigrants – others 0.47 0.72 0.58 0.58 0.73 0.65 0.77 0.67 0.70 0.76 0.76 0.69 0.34 0.37 0.32 Source: Israel Income Surveys 2005–2008; 1976–1981 birth cohorts. Source: Universities administrative data applicant’s cohorts 1999–2002. The results suggest that ethnic gaps in field of study among both males and females are already present at the application stage and, in fact, are larger among applicants than among graduates. Panel B of Table 3 provides a tabulation of field of study expected salary of university applicants, based on the field that each applied to, by ethnic origin group. The results show that the tripartite hierarchy in expected salary that exists among graduates is more pronounced among applicants. Among graduates, leading the pack at the admissions stage are FSU immigrants while immigrants from other countries chose majors that put them at the bottom of the hierarchy. In sum, the economic hierarchy among university graduates is already manifest in applicants’ field of study preferences. Even though economic returns are an important factor in choosing a university major, not all applicants translate this desire into application choices. Understanding the ethnic variation in major choice sets, and, consequently, the position of groups on the field of study economic hierarchy at the application stage, can go a long way toward explaining economic inequality among graduates. To this end, I will consider three explanations: selection into higher education, academic credentials, and aspirations. For the sake of parsimony, I focus on the distinct pathways of three ethnic groups: FSU immigrants (top of hierarchy); other first-generation immigrants (bottom of hierarchy); and veteran Ashkenazis (top of hierarchy). 4.2.1. Selection into the postsecondary education system One explanation for the ethnic variation in field of study choice sets at the application stage is variation in the likelihood of attending college. To estimate selection into higher education, I use the Israel Income Survey and focus on cohorts similar to those in the university applicant pool.23 Table 5 (column 1) reports the transition probability from high school to the postsecondary system for each group. High school graduates who are veteran Ashkenazi are the most likely of all groups to 23 Israel Income Surveys from 2005 through 2008. S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 473 0 Adjusted composite score [within each inst] 40 60 80 100 20 Composite academic score (percentile) Immigrants from FSU Immigrants - others Veteran ''Askenazi'' Fig. 1. The distribution of the composite academic score (percentile), applicants, 1999–2002. enter the postsecondary education system, with 64 percent of males and 72 percent of females doing so. This high rate likely captures the quality of their high school academic preparation, the economic resources at their disposal, access to information about higher education and the labor market, and guidance by parents, teachers, counselors, and others (Alon, 2009; Schneider, 2009). Conversely, FSU immigrants have the lowest rate of continuation: only 42 percent of males and 47 percent of females pursue an education after high school. Given this low rate, it is likely that only the best within this group—either in terms of observed characteristics (academic achievements) or unobserved characteristics (motivation and ambition)—make it to the university applicant pool. The continuation rate of immigrants from non-FSU countries is somewhere in between, with 53 percent of males and 58 percent of females enrolling in college. Taken together, these results suggest that the lower rate of transition into higher education (positive selection) of FSU immigrants is likely one of the reasons behind their lucrative major choice set. 4.2.2. Academic credentials It seems, however, that there is an even bigger culprit behind the high field of study economic ranking of veteran Ashkenazis than selection into higher education: namely, disparities in prior academic preparation. Fig. 1 displays the distributions of the academic composite scores (based on test scores and grades) of all applicants by ethnic group (the pattern was similar for both sex groups). This boxplot presentation reveals that veteran Ashkenazi applicants are the group with the highest prior achievements, on average. The group with the weakest academic scores is FSU immigrants (together with second-generation Mizrachi applicants whose results are not shown). The gaps are substantial: about half of veteran Ashkenazi applicants attained a score above the 60th percentile while only a quarter of FSU immigrants reached that threshold. Given the low academic standing of FSU immigrants, their lucrative major choice set is surprising—even their peers who immigrated from other countries, and who applied to fields with the lowest economic returns, have much better academic scores, on average. Taken together, these results reveal that the strong academic credentials of veteran Ashkenazi graduates are, as expected, an important factor in their high ranking in the expected earnings distribution upon labor market entry. Neither high school grades nor test scores, however, can explain the top application stage position of FSU immigrants or the bottom position of immigrants from non-FSU countries. 4.2.3. Aspirations and orientation Applicants’ occupational and academic aspirations may provide the missing piece of the puzzle regarding the position of the two immigrants groups on the field of study economic hierarchy at the application stage. FSU immigrants’ top position may reflect predilection toward STEM fields, which are typically selective and lucrative. About 35 percent of male FSU immigrant applicants had some kind of engineering major, which tend to top the list of starting salaries, as the most lucrative field in their major choice sets. At the same time, about 30 percent of male veteran Ashkenazi applicants had an engineering field in their choice sets, which puts them closer to other second- and third-generation groups at the application stage, compared to their superior position at the graduation stage. Among male immigrants from non-FSU countries—the group at the bottom of the expected earnings distribution as early as the application stage—only 20 percent chose an engineering field at application time. A humanities field was the most lucrative major in the choice set of 13 percent of this group, compared to less than 4 percent among FSU males. The pattern among female applicants is similar. To reveal the effect of economic aspirations and orientations on field of study choice set, net of prior academic achievements, I regress field of study salary on ethnic origin for applicants, admits and graduates, separately for men and women, controlling for an individual’s (standardized) academic composite score (veteran Ashkenazi is the omitted category). The results, presented in Tables 6a and 6b, demonstrate that the application stage economic disadvantage of some third- and second-generation groups, which arises from field of study choices, disappears, or even reverses in sign, when we take into 474 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Table 6a Ethnic gaps in field of study average monthly salary (in NIS), 1999–2002 (reference group: veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’), Males. MALES Applicants Variables (1) Gross 806.6⁄⁄⁄ (82.47) Immigrants – others 968.6⁄⁄⁄ (99.29) Two native-born parents 278.0*** (66.31) One native-born parent and one from Asia or Africa (veteran ‘‘Mizrachi’’) 98.78 (89.43) Both parents from Asia or Africa (2nd generation ‘‘Mizrachi’’) 207.7* (86.51) Both parents from Europe or America (2nd generation ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) 274.7** (87.84) One parent from Europe or America and one from Asia or Africa (mix ethnicity) 224.2 (130.9) Academic score Immigrants from FSU Missing acad. score Constant Observations R-squared 13,175*** 37,940 0.010 Admits Graduates (2) Net (3) Gross (4) Net (5) Gross (6) Net 1690⁄⁄⁄ (76.02) 276.5⁄⁄ (90.94) 75.24 (60.07) 381.7*** (81.13) 691.2*** (78.95) 67.78 (79.55) 220.3 (118.6) 67.18*** (0.762) 1049*** (55.70) 67.84 (94.05) 930.2⁄⁄⁄ (108.7) 275.8*** (69.96) 353.8*** (96.44) 378.2*** (91.74) 311.6*** (92.83) 199.1 (139.6) 746.8⁄⁄⁄ (82.18) 457.3⁄⁄⁄ (94.76) 134.7* (60.50) 154.3 (83.55) 555.1*** (80.05) 76.86 (80.30) 285.5* (120.8) 74.23*** (0.793) 688.2*** (65.98) 181.0 (137.3) 953.6⁄⁄⁄ (164.4) 390.7*** (101.8) 410.6** (138.5) 394.9** (133.3) 424.8** (136.4) 275.1 (205.6) 864.2⁄⁄⁄ (119.8) 440.9⁄⁄ (143.4) 209.4* (88.22) 156.7 (120.3) 588.8*** (116.6) 162.2 (118.3) 124.4 (178.3) 75.14*** (1.146) 1176*** (107.8) 9290*** 11,588*** 26,463 0.004 7099*** 11,942*** 13,456 0.004 7452*** 0.188 0.255 0.252 Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001. Table 6b Ethnic gaps in field of study average monthly salary (in NIS), 1999–2002 (reference group: veteran ‘‘Ashkenazi’’), Females. Females Applicants Variables (1) Gross 527.8⁄⁄⁄ (45.18) Immigrants – others 416.1⁄⁄⁄ (55.65) Two native-born parents 99.02* (39.04) One native-born parent and one from Asia or Africa (veteran ‘‘Mizrachi’’) 8.479 (50.55) Both parents from Asia or Africa (2nd generation ‘‘Mizrachi’’) 111.8* (48.94) Both parents from Europe or America (2nd generation ‘‘Ashkenazi’’) 154.9** (52.15) One parent from Europe or America and one from Asia or Africa (mix ethnicity) 108.3 (74.13) Academic score Immigrants from FSU Missing acad. score Constant Observations R-squared 7907*** 52,003 0.008 Admits Graduates (2) Net (3) Gross (4) Net (5) Gross (6) Net 1126⁄⁄⁄ (43.37) 20.04 (52.83) 31.69 (36.62) 330.2*** (47.57) 430.2*** (46.36) 1.804 (48.94) 132.0 (69.59) 36.66*** (0.448) 869.0*** (32.03) 237.9⁄⁄⁄ (44.36) 384.6⁄⁄⁄ (53.78) 112.4** (36.12) 56.95 (47.08) 211.0*** (45.26) 118.8* (48.30) 158.6* (68.89) 616.3⁄⁄⁄ (41.89) 177.9⁄⁄⁄ (50.45) 77.57* (33.62) 204.7*** (43.97) 246.8*** (42.63) 9.715 (44.99) 58.42 (64.20) 31.20*** (0.424) 613.8*** (34.40) 280.4⁄⁄⁄ (61.47) 383.8⁄⁄⁄ (78.69) 103.8* (51.91) 97.75 (66.71) 183.1** (64.26) 195.9** (69.29) 124.1 (98.71) 667.1⁄⁄⁄ (58.02) 210.8⁄⁄ (73.80) 54.51 (48.34) 193.0** (62.34) 242.3*** (60.44) 73.07 (64.54) 78.79 (91.97) 31.53*** (0.592) 625.6*** (51.56) 6089*** 7077*** 36,070 0.005 5448*** 7095*** 18,762 0.006 5501*** 0.128 0.138 0.138 Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001. account prior academic achievements (Model 2). A positive sign means that a group has economic aspirations (as observed in the economic value of applicants’ field of study choices) that exceed those of veteran Ashkenazi applicants with similar academic scores. Immigrants from the FSU apply to fields with the highest economic returns given their academic scores; their expected salary at the application stage exceeds that of veteran Ashkenazi applicants by 1700 and 1100 NIS for males and S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 475 Males 14,500 14,000 13,500 NIS 13,000 12,500 12,000 11,500 11,000 10,500 10,000 Applicants Admits Immigrants from FSU Graduates Veteran “Ashkenazi” Immigrants - others Females 9,000 8,500 NIS 8,000 7,500 7,000 6,500 6,000 Applicants Admits Immigrants from FSU Graduates Veteran “Ashkenazi” Immigrants - others Fig. 2. The field of study expected salary throughout the college pipeline, by ethnic origin group. females, respectively. Interestingly, second-generation Mizrachi applicants also have high economic aspirations relative to their academic qualifications; their edge in expected salary at the application stage is 690 and 430 NIS for males and females, respectively. These results demonstrate that an applicant’s test scores and grades do not constrain field of study economic aspirations and occupational ambitions in the same way across groups. The low academic credentials of FSU immigrants do not curb their high field of study economic aspirations while immigrants from other countries tend to aim lower than what their academic scores can match. Nonetheless, institutional admissions decisions can serve as a painful ‘‘reality check’’ for some ambitious applicants, and thus can narrow or expand the ethnic variation in expected salary among applicants. 4.3. Admission decisions and matching The admission stage is the point at which individual aspirations and academic credentials meet the academic requirements of fields of study. A group’s likelihood of admission is reported in Table 5 (column 2).24 FSU immigrants have the lowest admission rate: only 57 percent of males and 58 percent of females were admitted to one of the majors that they listed.25 Veteran Ashkenazi applicants have the highest admission rate (74 and 73 percent for males and females, respectively), and clearly the most realistic choice set, in that their academic achievements match the admission requirements of their choices. The admissions decision substantially narrows the application stage economic gap between the FSU and veteran Ashkenazi groups (among males the gap is eradicated). In fact, ethnic gaps in expected salary are smallest by the time that admissions decisions are made. This is demonstrated in Fig. 2, which displays the field of study expected salary for the three ethnic origin groups selected, from the application stage through admissions and to graduation. Clearly, applicants from all groups aimed for more lucrative majors than would admit them. Especially ambitious were male FSU immigrants: for them the plunge from application to admission, in terms of a major’s expected salary, is steepest. Taken together, the ethnic variation depicted in the application and admission stages provides important insights regarding the match between applicants’ academic and economic aspirations, on the one hand, and the academic requirements of the fields of study they have listed, on the other. Clearly, the economic value of FSU immigrants’ choices generally overmatches, using Bowen et al.’s (2009) terminology, their academic and admission potential—that is, they apply to majors 24 25 I also gauged the ethnic gaps in admission likelihoods net of academic scores (results are available upon request). They make up 12 percent of all male applicants, but only 9.5 percent of the male admit pool (the numbers for females are 15 and 12 percent, respectively). 476 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 associated with high salaries, but these majors require scores that are generally higher than this group’s academic qualifications. This pattern of overmatching—economic aspirations that exceed qualifications—is also found in high-achieving applicants from traditionally weak groups, namely second- and third-generation Mizrachi applicants. The contrast in the case of non-FSU first-generation immigrants, who tend to choose fields with low expected salaries, even net of academic scores, is glaring: this group’s economic aspirations greatly undermatch its academic potential, especially among those with high academic achievements.26 In sum, applicants from groups at the bottom of the socioeconomic hierarchy are the most likely to apply to fields of study that either over- or undermatch their academic qualifications, while those from strong socioeconomic groups (i.e., veteran Ashkenazi applicants) are least likely to display either overmatching or undermatching patterns in their field of study choices. 4.4. Persistence until degree attainment The graduation stage is also important for understanding the positions of groups in the field of study economic hierarchy because not all students who matriculate persist until degree attainment. Moreover, among those who do persist, not all obtain a degree in the field that they first enrolled in. Among male students, FSU immigrants have the highest dropout rate: only 65 percent eventually attain a degree, compared to 71 percent of veteran Ashkenazi males (see Table 5, column 4). Only 29 percent of male FSU immigrants who applied to selective universities in Israel between 1999 and 2002 graduated from the institution that they first enrolled in, compared to 38 percent of veteran Ashkenazi applicants (Table 5, column 5) and 32 percent of immigrants from other countries. The gaps among females are smaller, and the persistence rate of female FSU immigrants is slightly greater than that of female immigrants from other countries. Overall, the ethnic variation in expected salary among females holds steady from the admission to graduation stages, while the variation among males expands slightly after enrollment due to differential attrition rates (see Fig. 2 and Table 6).27 5. Discussion This study demonstrates that field of study variation is a key factor in explaining economic inequality among workers with a bachelor’s degree. This area of research has great potential to shed light on earnings differentials by gender, racial, ethnic, and immigration status in many countries, not least because we live in an era when the stratification of the returns to education continues to intensify. This study shows that field of study inequality changes throughout the college pipeline, from an applicant’s major choice set to the type of degree attained, and quantifies the consequences of this process for groupbased economic inequality. What leverage do we gain from considering the entire college pipeline for the purpose of understanding economic inequality between groups? In a world where all groups had a cumulative trajectory from K-12 to the labor market, measuring ethnic-based economic inequality by field of study at one stage—for example, upon graduation—would provide an accurate picture of the economic position of groups. Consider, for example, veteran Ashkenazis in Israel, who have the highest expected salary among second- and third-generation university graduates. They are a paradigm of the process of cumulative advantage (DiPrete and Eirich, 2006): they have the best K-12 academic preparation; the finest understanding of the higher education system, which results in ambitious, yet realistic, aspirations for field of study choices; the greatest ability to deal with the academic rigor of elite universities and the selective fields within them; and, consequently, the highest chances of persisting until degree attainment. Ultimately, as a group, they have the best economic prospects in the labor market because a large share of them obtains lucrative degrees. A cross-sectional assessment can accurately capture their advantaged position: at any window of observation—be it the application stage, after the admission decision, or at graduation time—they are at the top of the hierarchy. However, not all groups follow a cumulative trajectory. Consider, for example, FSU immigrants in Israel, who, like veteran Ashkenazis, are at the top of the expected salary list at both the application stage and after graduation. A cross-sectional glimpse at either stage would yield a misleading picture of a group that holds a highly advantaged position. But a more comprehensive look at the college process leads to a very different conclusion: the economic prospects of FSU immigrants as a group are less than stellar, mainly because many of them do not attend college, and among those who do, a substantial share drop out. They have high ambitions and occupational aspirations, but these do not fully compensate for their subpar academic preparation, which results in a low continuation rate into the postsecondary education system and a high attrition rate from college. This nuanced understanding is only possible when we take into account the greater pipeline that leads to a bachelor’s degree. Moreover, if the process shaping field of study inequality was cumulative throughout the college pipeline, we would expect field of study stratification to expand systematically from stage to stage. But the formation of inequality in Israel (and likely in other countries as well) is not cumulative, in that the gaps in expected salary among applicants shrink at the admission stage but later expand during the college years due to attrition and differential selection processes. In order 26 High-achieving applicants in all other groups applied to more lucrative fields (based on a specification that includes interaction terms between origin and academic scores; results are available upon request). 27 In addition, what we see for males, but not for females, is that expected salary is higher among graduates than among admits. This suggests that attrition, among all groups, is not random: those enrolled in more lucrative fields are more likely to graduate than those in less lucrative fields. S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 477 to interpret the economic position of various groups upon labor market entry and to understand the mechanisms that generate inequality in such a complex world, we need to employ a longitudinal perspective that incorporates the college pipeline as an integral part of the investigation. As the findings in this study demonstrate, we can learn a great deal about the mechanisms that generate inequality from studying field of study choices. To some extent, the orientation towards field of study is constrained and stratified by academic preparation in the K-12 system. But what this study reveals is that there are other factors that play a key role in the development of the choice set and, thus, contribute to the non-cumulative pattern of field of study inequality, including orientation, preferences and aspirations, as well as knowledge about the higher education system and its link to labor market outcomes (Alon and DiPrete, 2015; Schneider and Stevenson, 1999; Schneider, 2009). While applicants from groups at the bottom of the socioeconomic hierarchy tend to exhibit under- or overmatching patterns (applying to majors with academic thresholds that are lower or higher, respectively, than one’s academic scores) in terms of field of study expected salary, the aspirations of those from strong socioeconomic groups tend to match their admission potential. Thus, field of study matching proved itself to be not only a marker of socioeconomic advantage, but also an indicator of success in college and labor market prospects. From this vantage point, mapping the decision making process behind the formation of the field of study choice set can yield important insights about the roots of gender, racial/ethnic, and class-based inequality. Taken together, connecting the pieces of the puzzle that shape field of study inequality—including K-12 academic preparation, ambitions, aspirations, application patterns, and differential selection and attrition processes during high school and college—is useful for understanding the gaps in earnings among workers with a bachelor’s degree. Analyzing the college pipeline, a strategic point in the school-to-work transition, helps determine to what extent wage inequality among university graduates is generated before, during, and after college, and helps devise policies aimed at eradicating persistent social and economic gaps between ethnic and gender groups. Acknowledgments This research was supported by Grants #200800120 and #200900169 from the Spencer Foundation. I thank Ori Katz for research assistance. References Alon, Sigal, 2009. The evolution of class inequality in higher education: competition, exclusion, and adaptation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 74 (5), 731–755. Alon, Sigal, 2011. The diversity dividends of a need-blind and color-blind affirmative action policy. Soc. Sci. Res. 40 (6), 1494–1505. Alon, Sigal, DiPrete, Thomas A., 2015. Gender differences in the formation of field of study choice set. Sociol. Sci. 2, 50–81. Alon, Sigal, Gelbgiser, Dafna, 2011. The female advantage in college academic achievements and horizontal sex segregation. Soc. Sci. Res. 40 (1), 107–119. Altonji, Joseph G., Blank, Rebecca M., 1999. Race and gender in the labor market. In: Orley, A., Card, D. (Eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 3, C. Elsevier, pp. 3143–3259 (Chapter 48). Altonji, Joseph G., Blom, Erica, Meghir, Costas, 2012. Heterogeneity in human capital investments: high school curriculum, college major, and careers. Annu. Rev. Econ. 4, 185–223. Arcidiacono, Peter, 2004. Ability sorting and the returns to college major. J. Econ. 121 (1–2), 343–375. Arcidiacono, Peter, Aucejo, Esteban M., Spenner, Ken, 2012. What happens after enrollment? An analysis of the time path of racial differences in GPA and major choice. IZA J. Labor Econ. 1 (1), 1–24. Ayalon, Hanna, 2008. Who study what, where and why? The consequences of the expansion of the Israeli higher education system. Israeli Sociol. 2, 33–60 (in Hebrew). Blau, Francine D., Beller, Andrea H., 1992. Black–white earnings over the 1970s and 1980s: gender differences in trends. Rev. Econ. Stat. 74 (2), 276–286 Bowen, William G., Chingos, Matthew M., McPherson, Michael S., 2009. Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities. Princeton University Press, NJ. Carnevale, Anthony P., Strohl, Jeff, Melton, Michelle, 2011. What’s It Worth?: The Economic Value Of College Majors. Center on Education and the Workforce. Georgetown University. <https://cew.georgetown.edu/whatsitworth>. Cohen, Yinon, Haberfeld, Yitchak, 1998. Second-generation Jewish immigrants in Israel: have the ethnic gaps in schooling and earnings declined? Ethnic Racial Stud. 21 (3), 507–528. Cohen, Yinon, Haberfeld, Yitchak, Kristal, Tali, 2007. Ethnicity and mixed ethnicity: educational gaps among Israeli-born Jews Ethnic Racial Stud. 30 (5), 896–917. Dahan, Momi, Mironichev, Natalia, Dvir, Eyal, Shye, Shmuel, 2002. Have the educational gaps narrowed? Econ. Q. (Hebrew) 49 (1), 159–188. Des Jardins, Stephen L., Ahlburg, Dennis A., McCall, Brian P., 2002. A temporal investigation of factors related to timely degree completion. J. Higher Educ. 73 (5), 555–581 (Sep.–Oct., 2002). DiPrete, T.A., Buchmann, C., 2013. The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and what it Means for American Schools. Russell Sage Foundation, New York. DiPrete, Thomas A., Eirich, Gregory M., 2006. Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: a review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 32, 271–297. Fisher, A., Margolis, J., 2002. Unlocking the Clubhouse: the Carnegie Mellon experience. SIGCSE Bull. 34 (2), 79–83. Friedlander, Dov, Okun, Barbra S., Eisenbach, Zvi, Elmakias, Lilach L., 2002. Immigration, social change and assimilation: educational attainment among birth cohorts of Jewish Ethnic Groups in Israel, 1925–29 to 1965–69. Popul. Stud. 56 (2), 135–150. Gshur, Binyamin, Okun, Barbara S., 2003. Generational effects on marriage patterns: Jewish immigrants and their descendants in Israel. J. Marriage Family 65 (2), 287–301. Haberfeld, Yitchak, Cohen, Yinon, 2007. Gender, ethnic, and national earnings gaps in Israel: the role of rising inequality. Soc. Sci. Res. 36 (2), 654–672. Hällsten, Martin, 2010. The structure of educational decision making and consequences for inequality: a Swedish test Case1. Am. J. Sociol. 116 (3), 806–854. Hearn, James C., Olzak, Susan, 1981. The role of college major departments in the production of sexual inequality. Sociol. Educ. 54, 195–205. Hoxby, Caroline M., Avery, Christopher, 2012. The Missing ‘‘One-Offs’’: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low Income Students. Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS), 2009. Table 15: Recipients of a First Degree from Universities by Sex, Population Group, Religion, Origin and Field of Study. Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem, Israel. Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS), 2010. Table 2.22: Jews, by Continent of Origin, Sex and Age. Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem, Israel. 478 S. Alon / Social Science Research 52 (2015) 465–478 Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS), 2012. Characteristics of Studies and Integration into the Labour Market among First-Degree Recipients from Institutions of Higher Education in Israel, 1999–2008. Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem, Israel. Publication No. 1471. Jayanti, Owens, Lynch, Scott M., 2012. Black and Hispanic immigrants’ resilience against negative-ability racial stereotypes at selective colleges and universities in the United States. Sociol. Educ. 85 (4), 303–325. Juhn, Chinhui, Murphy, Kevin M., Pierce, Brooks, 1991. Accounting for the slowdown in black–white wage convergence. In: Kosters, M. (Ed.), Workers and their Wages. AEI Press, Washington, DC, pp. 107–143. Leppel, Karen, 2001. The impact of major on college persistence among freshmen. High. Educ. 41, 327–342. Lucas, Samuel R., 2001. Effectively maintained inequality: education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. Am. J. Sociol. 106 (6), 1642– 1690. Manski, Charles F., 1983. College Choice in America Harvard University Press. Margolis, J., Estrella, R., Goode, J., Holme, J., Nao, K., 2008. Stuck in the Shallow End: Education, Race, and Computing. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. McFadden, Daniel, 1974. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka, P. (Ed.), Frontiers in Econometrics. Academic Press, New York, pp. 105–142. Montmarquette, Claude, Cannings, Kathy, Mahseredjian, Sophie, 2002. How do young people choose college majors? Econ. Educ. Rev. 21 (6), 543–556. Okun, Barbra S., 2004. Insight into ethnic flux: marriage patterns among Jews of mixed ancestry in Israel. Demography 41 (1), 173–187. Okun, Barbara S., Friedlander, Dov, 2005. Educational stratification among Arabs and Jews in Israel: historical disadvantage, discrimination, and opportunity. Popul. Stud. 59 (2), 163–180. Okun, Barbara S., Khait-Marelly, Orna, 2008. Demographic behaviour of adults of mixed ethnic ancestry: Jews in Israel. Ethnic Racial Stud. 31 (8), 1357– 1380. Price, J., 2010. The effect of instructor race and gender on student persistence in STEM fields. Econ. Educ. Rev. 29 (6), 901–910. Reimer, David, Pollak, Reinhard, 2005. The Impact of Social Origin on the Transition to Tertiary Education in West Germany 1983 and 1999. Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung Mannheim. Riegle-Crumb, Catherine, King, Barbara, 2010. Questioning a white male advantage in STEM examining disparities in college major by gender and race/ ethnicity. Educ. Res. 39 (9), 656–664. Roksa, Josipa, Levey, Tania, 2010. What can you do with that degree? College major and occupational status of college graduates over time. Soc. Forces 89 (2), 389–415. Rumberger, Russell W., Thomas, Scott L., 1993. The economic returns to college major, quality and performance: a multilevel analysis of recent graduates. Econ. Educ. Rev. 12 (1), 1–19. Schneider, Barbara, 2009. College Choice and Adolescent Development: Psychological and Social Implications of Early Admission. National Association for College Admission Counseling, Discussion Paper. Schneider, B., Stevenson, D., 1999. The Ambitious Generation: American’s Teenagers, Motivated but Directionless. Yale University Press. Steele, C.M., 1997. A threat in the air – how stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am. Psychol. 52 (6), 613–629. Steele, C.M., Aronson, J., 1995. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test-performance of African-Americans. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69 (5), 797–811. Suresh, R., 2006. The relationship between barrier courses and persistence in engineering. J. College Stud. Retent. 8 (2), 215. Suzzman, Noam, Furman, Orly, Caplan, Tom, Romanov, Dmitri, 2007. The Quality of Israeli Academic Institutions: What the Wages of Graduates Tell about it? The Economics of Higher Education (EHE). Van de Werfhorst, Herman G, De Graaf, Nan D., Kraaykamp, Gerbert, 2001. Intergenerational resemblance in field of study in the Netherlands. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 17 (3), 275–293. Weinberger, Catherine J., 1998. Race and gender wage gaps in the market for recent college graduates. Ind. Relat. 37, 67–84. Wiswall, Matthew, Zafar, Basit, 2013. How do College Students Respond to Public Information about Earnings. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report (516). Xie, Yu, Shauman, Kimberle A., 2003. Women in Science: Career Processes and Outcomes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Yaish, Meir, 2001. Class structure in a deeply divided society: class and ethnic inequality in Israel, 1974–1991. Br. J. Sociol. 52 (3), 409–437. Yashiv, Eran, Kasir, Nitsa, 2009. Arab Israelis: Patterns of Labor Force Participation. Research Department, Bank of Israel.

© Copyright 2026