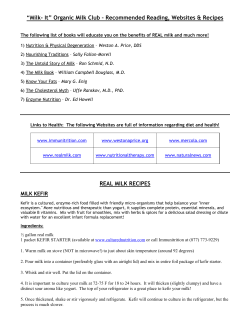

Document 163008