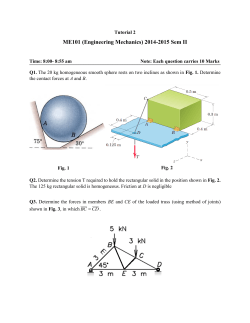

- UM Repository

Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 38 (2015) 113–118 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mssp Synthesis of vertically aligned flower-like morphologies of BNNTs with the help of nucleation sites in Co–Ni alloy Pervaiz Ahmad, Mayeen Uddin Khandaker n, Yusoff Mohd Amin Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia a r t i c l e i n f o PACS: 81.07.De Keywords: h-BN BNNTs Vapor deposition Vertically aligned abstract A Co–Ni alloy deposited at the top of Si substrate produces nucleation sites when etches with ammonia. The as-produced nucleation sites are used as a pattern to grow flower-like morphologies of vertically aligned Boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) in the present study. HR-TEM micrographs show black-blur like morphology on the outer part of the BNNTs. The sample contains BNNTs with and without internal bamboo like structures. XPS survey shows B 1s and N 1s peaks at 191 eV and 398 eV that indicate the presence of Boron and Nitrogen components in the synthesized sample. Raman spectrum shows a major peak at 1370 cm 1 that corresponds to E2g mode of h-BN. The as-synthesized BNNTs can be used for its potential applications without any further purification. & 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction BNNTs are one of the basic building blocks in nanotechnology. Their diameter independent electronic properties have covered the deficiencies of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) for different applications in the field of microelectronic mechanical systems (MEMs) [1]. The properties of BNNTs are almost similar to CNTs, however, CNTs can be conductor or semiconductor depends on the chirality or helicity, whereas BNNTs are wide band gap semiconductor independent of helicity [2–4]. The excellent electrical and mechanical properties of the BNNTs have made it a very important material for different applications in the scientific world of nanotechnology. It has been successfully explored for its potential applications in the field of engineering ceramics and polymeric composites [5]. The possible role of BNNTs as an insulating protective shield has also been observed in the development of nanocables from semiconductor nanowires [6–12]. It is experimentally observed that the superplasticity of engineering ceramics increases to a great extent with the addition of BNNTs [13]. Due to the bipolar nature of B–N n Corresponding author. Tel.: þ60 1115402880; fax: þ 60 379674146. E-mail address: [email protected] (M.U. Khandaker). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2015.04.017 1369-8001/& 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. bond, BNNTs showed stronger adsorption of hydrogen. Therefore, they are considered a very important material for hydrogen storage applications [14–18]. Furthermore, BNNTs can also be used for changing optical properties of materials in the systems [19,20]. The potential use of BNNTs for any of the above applications depends on its purity, size, morphology and alignment. Purity of the BNNTs is one of the most important factors for its use in any of its potential application. Therefore, the main target of the earlier researchers was not only the quantity but also the quality of the final product [21]. After it has been proposed that vertically aligned BNNTs can be used for its potential applications without further purification, researchers have tried to obtain this format of the BNNTs. However, in this regard no appreciable success has been achieved as compare to its structure counterpart CNTs. In this regard, some of the earlier work seems to be no more than a claim. In which, vertically aligned BNNTs bundles have claimed via plasma enhanced pulse laser deposition (PE-PLD) at a lower temperature of 600 1C [22]. The reported SEM morphology of the asclaimed BNNTs bundle is seem to be no more than an upward blur from a point-like structure on the substrate. In spite of high magnification SEM analysis, the vertical aligned morphology was so un-cleared that a separate 114 P. Ahmad et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 38 (2015) 113–118 sketch was drawn and shown with SEM micrographs to indicate the vertical alignment [22]. The reported BNNTs had not only un-cleared morphology (via SEM) but also had a shorter length in the range of a few hundred's nanometers. Furthermore, the experimental set up utilized in the synthesis technique (PE-PLD) is so complex and expensive to be hardly utilized by new researchers with limited budget or research funding. Therefore, until now, almost no further progress has been shown via purely this technique in the synthesis of aligned BNNTs. Pattern growth of BNNTs was obtained via combination of pulse laser deposition (PLD) and thermal CVD technique. PLD was used to deposit a uniform thin film of MgO on Si substrate and thermal CVD technique was used to grow BNNTs from B, MgO and FeO as precursors. Though BNNTs were grown in a particular pattern, however, they were only partially vertically aligned and were not strong enough to stand against a slight mechanical compression [23]. In our previous study [24], we have successfully grown vertically aligned BNNTs on Si substrate by combining the logic of vertically aligned CNTs [25] and Pattern growth of BNNTs [23]. In that technique, a uniform thin film of 1.5 mm was first deposited at the shining surface of Si substrate. B, MgO and γ-Fe2O3 were used as precursors in a temperature of 1000–1200 1C. Vertically aligned BNNTs were grown on the alumina deposited Si substrate in the presence of Argon gas flow as a reaction atmosphere. Though, BNNTs were synthesized in vertically aligned format, however, the diameter of the as synthesized BNNTs was highly nonuniform in the range of below 100 to 580 nm. The size and density of nucleation sites formed in the alumina deposited thin film on the substrate due to ammonia etching were thought to be the main factors responsible for this reason (irregular diameter). Therefore, it has been tried to search for such a type of catalysts or their alloys (to be deposited at the top of Si substrate) which have high etching rate with ammonia to produce nucleation sites with higher density. In this regard the previous work on vertically aligned CNTs [25] was further searched and Co–Ni alloy is found to be the most suitable materials to help in the synthesis of vertically aligned BNNTs. Thus, a thin layer of Co–Ni alloy is deposited at the shining surface of Si substrate. During the NH3 etching, the nucleation sites produced in the deposited alloy is followed by the BNNTs as a pattern to grow in the vertical aligned format. The detail methodology, obtained results and growth mechanism are fully described in the coming sections. 2. Experimental details A sample of vertically aligned flower-like morphologies of BNNTs is synthesized on Si substrate coated with a thin Fig. 1. FESEM micrographs of vertically aligned flower-like morphologies of BNNTs. (a) Lower magnification top view of the BNNTs. (b) Higher magnification top view shows BNNTs below the flower-like morphologies. (c) Higher magnification FESEM micrograph shows vertically aligned BNNTs wrapped up in flower-like morphologies. (d) Separate higher magnification micrograph of flower-like morphologies. P. Ahmad et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 38 (2015) 113–118 115 Fig. 2. Cross-sectional FESEM view of vertically aligned flower-like morphologies of BNNTs. layer of Co–Ni alloy. A mixer (200 mg) of Boron, MgO, and γ-Fe2O3 powder in a 2:1:1 weight ratio is used as a precursor. These precursors are put in alumina boat. The boat is covered with a few Si substrates and placed inside one end closed quartz tube. The quartz tube is then pushed into the horizontal quartz tube chamber of the furnace in such a way that the opened end of the tube is toward the gas inlet. The furnace is tightly sealed to prevent the effects of outside environment on the experimental parameters inside the furnace. Before the experiment, argon (Ar) gas is passed through the system to remove air and dust particles and to create an inert atmosphere. At the same time, the precursors are heated up to 1000 1C in the presence of Argon gas flow. At 1000 1C, argon flow is stopped, and NH3 gas is introduced into the system at a flow rate of 100–200 sccm. In the presence of NH3 flow, the system is further heated up to 1200 1C and kept for 1-h. After 1-h, NH3 flow is stopped, and the system is allowed to cool down to room temperature in the presence of Ar gas. At room temperature white color BNNTs are found deposited on Si substrate with good quality of adhesion and on the inner walls of alumina boat. 3. Results and discussion Fig. 1(a) shows the low magnification FESEM micrograph (top view) of the BNNTs synthesized in the present study. The top view shows flower-like morphologies with some empty spaces in-between. The flower-like morphologies can clearly be viewed in high magnification FESEM micrograph as shown in Fig. 1(b). The higher magnification micrograph not only gives a clear view of the flower-like morphologies but also of BNNTs in the empty space. The BNNTs in the empty spaces are indicated with the help of white circles in Fig. 1(b). The observation showed that most of the flower-like morphologies lied at the top surface of the BNNTs. Due to these morphologies BNNTs cannot be clearly identified in the current micrograph. Therefore, it was strongly felt to separately analyze both BNNTs and the flower-like morphologies in higher magnification. The results thus obtained are shown in Fig. 1(c) and (d). Fig. 1(c) shows high magnification FESEM micrograph of the BNNTs. The micrograph shows that all the BNNTs are covered or wrapped in cotton-like morphologies. These morphologies seem like the growth species that were still in process to become the part of the BNNTs in the form of hBN layers, however, due to incomplete growth it remains stuck with BNNTs and appeared in the current shape. Most of the BNNTs seemed to be vertically aligned. These aligned BNNTs can be used for its potential applications without further purification [26]. Some flower-like morphologies can also be found in Fig. 1(c) indicated by white circles. These flower-like morphologies are separately analyzed and shown in higher magnification in Fig. 1(d). It seems that the flower-like morphologies are under-developed BNNTs. In other words, h-BN species combine and make layers tubular structures of nanoscale h-BN. The mechanism thus developed during the growth of BNNTs is described at the end of the paper and schematically shown via a sketch in Fig. 6. FESEM is also employed to take a cross-sectional view of the as-synthesized flower-like morphologies of BNNTs to further verify its vertically aligned format. For this purpose, a small portion of the BNNTs on the substrate is carefully scratched from one side with the help of a sharp blade and analyzed with FESEM. The as-obtained FESEM micrograph is shown in Fig. 2. The figure shows vertically aligned BNNTs. No flower-like morphologies can be seen or observed in the current micrograph. Since, it is a crosssectional view in which mostly the lower part of the BNNTs is observed, therefore, the undeveloped or flowerlike structures at the top cannot be seen here. Most of the aligned BNNTs are straight, however, some of them can also be found with a bit curve parts. Some of the BNNTs are bent after their growth to a certain point. These bent or curved parts suggest that, after grown to a certain point, BNNTs need support to remain vertically align. This support can only be provided with the nearby BNNTs, which in other words depend on the density of nucleation sites i.e. higher the density of nucleation sites, the more align BNNTs will grow [25]. Along with BNNTs some broken species can also be found in the current micrograph which might have formed or included due to scratching of sample with blade. 116 P. Ahmad et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 38 (2015) 113–118 Fig. 3. TEM analysis of flower-like BNNTs sample. (a) Low and (b) high resolution TEM images show BNNT internal bamboo like structure. (c) Low and (d) high resolution TEM images of another BNNT without bamboo like structure. (e) Higher resolution TEM image shows lattice fringes on BNNT surface. (f) BNNT has interlayer spacing of 0.34 nm. Fig. 3 shows transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs of the synthesized BNNTs in low and high resolution. Fig. 3(a) shows the low resolution TEM micrograph of an individual BNNT characterized from the present sample. The micrograph shows a black-blur like morphology on the outer part of the BNNT. The internal part of the tube is found to contain an irregular bamboo-like structure. Due to this irregular shape of the bamboo-like structure, the wallthickness or external diameter of the BNNT varies in the range of 40–70 nm, whereas the total diameter is found to be 128 nm. A high resolution TEM micrograph of the same BNNT is also obtained (and shown in Fig. 3(b)) to further clarify its internal and external morphology. The micrograph shows a clear view of the BNNT internal bamboo like structure with a variable diameter [21,27]. The black-blur like structure can still be seen or viewed at this resolution. Fig. 3(c) shows low resolution TEM micrograph of another BNNT from the same sample. No internal bamboo like structure can be seen in the current BNNT. The tube has almost uniform wall-thickness and an internal diameter of 34 nm and total diameter of 100 nm. The black-blur like morphologies can also be found attached with BNNT. This BNNT is also viewed in high resolution and shown in Fig. 3(d). The high resolution micrograph confirmed the structure of the BNNT illustrated in Fig. 3(c) with black-blur like morphologies and without internal bamboo like structure. Its external part is separately shown in further higher resolution in Fig. 3(e). At this resolution lattice fringes can P. Ahmad et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 38 (2015) 113–118 be seen on the BNNT surface. These lattice fringes are further clarified in Fig. 3(f), which shows that the BNNT has multilayers structure with an interlayer spacing of 0.34 nm. This interlayer spacing is the characteristics of d(002) spacing of hBN [28] and its highly crystalline nature. This crystalline nature of the BNNT is found to be of great interest in the development of a solid state neutron detector [29]. The elemental composition of the synthesized BNNTs is analyzed with the help of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The as-obtained XPS survey is shown in Fig. 4. XPS survey shows B 1s and N 1s peaks at 191 eV and 398 eV that confirmed B and N elemental composition of the synthesized BNNTs [30,31]. The smaller intensity O 1s peak at 533 eV shows content of oxygen which may either be due to as-used Si substrate, B2O3 or B(OH)3 [32]. The composition and phase of the BNNTs are find out with the help of Raman spectroscopy. The as-obtained Raman spectrum is shown in Fig. 5. Raman spectrum shows a major peak at 1370 cm 1 that corresponds to E2g mode of h-BN [33]. Along with the major peak, a smaller intensity peak is also detected in the Raman spectrum at 1126.33 cm 1 for the presence of B(OH)3, which might have formed by the spontaneous reaction of boron and B2O3 (left during the synthesis of BNNTs) with moisture and oxygen in the air due to laser interaction [34]. 117 The mechanism for the synthesis of vertically aligned flower-like morphologies of BNNTs in the present study is described via a sketch shown in Fig. 6. The precursors at higher temperature ( 1000 1C) produce growth species (B2O2). When NH3 is introduced in to the system at 1000 1C, it plays a dual role [24]. On one side it acts as an etching agent and on the other side provides N2 for the formation of h-BN species. As an etching agent it etches away the Ni particles from the deposited Co–Ni alloy (because Ni has higher etching rate as compare to Co) on the Si substrate and produces nucleation sites in the Co particles. The density of the nucleation sites is dependent on the etching rate of NH3 i.e. the higher the etching rate the more nucleation sites will be prodeced [25]. The N2 from decomposed NH3 reacts with already formed B2O2 (from the reaction of B and metal oxides precursors) and synthesize h-BN species in the form of vapors. These vapors are deposited on the substrate and grow in the tubular structure following the nucleation sites as pattern. The density of nucleation sites and starting diameter of the tubes are playing a key role in its vertical align format [25]. Because of this, the nearby BNNTs are acting as a support for each other. The increasing length of the tubes causes a gradual decrease in the diameter which in other words effect the alignment of the BNNTs [24]. 4. Conclusions Fig. 4. XPS survey shows B 1s and N 1s peaks at 191 eV and 398 eV that indicate h-BN nature of the BNNTs. The O 1s peak at 533 eV shows content of oxygen which may either be due to substrate, B2O3 or B (OH) 3. Synthesis of vertically aligned BNNTs with the help of Co–Ni alloy deposited at the top of Si substrate showed that the substrate's nature and the types of catalysts has a key role in controlling the size, morphology and alignment of BNNTs. The alignment of the BNNTs during the synthesis is found to depend on their support to each other, which in other word depends on the density of nucleation sites and diameter of the tubes. Flower-like and black-blur like morphologies observed during FESEM and HR-TEM microscopies indicates continues layer growth of the BNNTs. Changes in the experimental parameters like: separate NH3 etching of the catalysts deposited substrate, temperature, growth duration and annealing of precursors are further be helpful to grow high quality vertically align BNNTs. The synthesized BNNTs are found to be of great Fig. 5. Raman spectrum shows a major peak at 1370 (cm 1) that corresponds to E2g mode of h-BN. 118 P. Ahmad et al. / Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 38 (2015) 113–118 Fig. 6. A sketch of the growth mechanism for the BNNTs synthesized in the present study. interest for its potential application in the field of biomedical, microelectronic mechanical system, targeted drug delivery and solid state neutron detector. Acknowledgments We are extremely grateful to University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia, Project number: RG37515AFR, for providing funds and facilities for our research work. References [1] P. Ahmad, M.U. Khandaker, Y.M. Amin, Indian J. Phys. 89 (2015) 209–216. [2] M. Ishigami, S. Aloni, A. Zettl, Properties of boron nitride nanotubes, in: Proceedings of the AIP Conference, 2003, pp. 94–99. [3] A. Maguer, E. Leroy, L. Bresson, E. Doris, A. Loiseau, C. Mioskowski, J. Mater. Chem. 19 (2009) 1271–1275. [4] Y. Huang, J. Lin, J. Zou, M.-S. Wang, K. Faerstein, C. Tang, Y. Bando, D. Golberg, Nanoscale 5 (2013) 4840–4846. [5] N.P. Bansal, J.B. Hurst, S.R. Choi, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 89 (2006) 388–390. [6] C. Tang, Y. Bando, T. Sato, K. Kurashima, Adv. Mater. 14 (2002) 1046–1049. [7] W.S. Jang, S.Y. Kim, J. Lee, J. Park, C.J. Park, C.J. Lee, Chem. Phys. Lett. 422 (2006) 41–45. [8] L.W. Yin, Y. Bando, Y.C. Zhu, D. Golberg, M.S. Li, Adv. Mater. 16 (2004) 929–933. [9] Y.-C. Zhu, Y. Bando, D.-F. Xue, F.-F. Xu, D. Golberg, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (2003) 14226–14227. [10] Y. Zhang, K. Suenaga, C. Colliex, S. Iijima, Science 281 (1998) 973–975. [11] K. Suenaga, C. Colliex, N. Demoncy, A. Loiseau, H. Pascard, F. Willaime, Science 278 (1997) 653–655. [12] J. Wang, C.H. Lee, Y.K. Yap, Nanoscale 2 (2010) 2028–2034. [13] Q. Huang, Y. Bando, X. Xu, T. Nishimura, C. Zhi, C. Tang, F. Xu, L. Gao, D. Golberg, Nanotechnology 18 (2007) 485706. [14] A. Leela Mohana Reddy, A.E. Tanur, G.C. Walker, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35 (2010) 4138–4143. [15] G. Mpourmpakis, G.E. Froudakis, Catal. Today 120 (2007) 341–345. [16] S. Hu, E.-J. Kan, J. Yang, J. Chem. Phys. 127 (2007) 164718. [17] S. Shevlin, Z. Guo, Phys. Rev. B 76 (2007) 024104. [18] E. Durgun, Y.-R. Jang, S. Ciraci, Phys. Rev. B 76 (2007) 073413. [19] B. Akdim, R. Pachter, X. Duan, W.W. Adams, Phys. Rev. B 67 (2003) 245404. [20] B.-C. Wang, M.-H. Tsai, Y.-M. Chou, Synth. Met. 86 (1997) 2379–2380 . [21] C. Zhi, Y. Bando, C. Tan, D. Golberg, Solid State Commun. 135 (2005) 67–70. [22] J.S. Wang, V.K. Kayastha, Y.K. Yap, Z.Y. Fan, J.G. Lu, Z.W. Pan, I.N. Ivanov, A.A. Puretzky, D.B. Geohegan, Nano Lett. 5 (2005) 2528–2532. [23] C.H. Lee, M. Xie, V. Kayastha, J.S. Wang, Y.K. Yap, Chem. Mater. 22 (2010) 1782–1787. [24] P. Ahmad, M.U. Khandaker, Y.M. Amin, Mater. Manuf. Process. (2014). [25] C.J. Lee, D.W. Kim, T.J. Lee, Y.C. Choi, Y.S. Park, Y.H. Lee, W.B. Choi, N.S. Lee, G.-S. Park, J.M. Kim, Chem. Phys. Lett. 312 (1999) 461–468. [26] J. Wang, M. Xie, Y. Khin Yap, Optimum growth of vertically-aligned boron nitride nanotubes at low temperatures, in: Proceedings of the APS Meeting Abstracts, 2007, pp. 31008. [27] Z. Zhang, B. Wei, G. Ramanath, P. Ajayan, Appl. Phys. Lett. 77 (2000) 3764–3766. [28] D. Golberg, Y. Bando, C. Tang, C. Zhi, Adv. Mater. 19 (2007) 2413–2432. [29] P. Ahmad, N.M. Mohamed, Z.A. Burhanudin, A review of nanostructured based radiation sensors for neutron, in: Proceedings of the AIP Conference, 2012, pp. 535. [30] S. Sinnott, R. Andrews, D. Qian, A. Rao, Z. Mao, E. Dickey, F. Derbyshire, Chem. Phys. Lett. 315 (1999) 25–30. [31] C.-Y. Su, W.-Y. Chu, Z.-Y. Juang, K.-F. Chen, B.-M. Cheng, F.-R. Chen, K.-C. Leou, C.-H. Tsai, J. Phys. Chem. C 113 (2009) 14732–14738. [32] J.F. Moulder, W.F. Stickle, P.E. Sobol, K.D. Bomben, Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, Perkin-Elmer, Eden Prairie, MN, 1992. [33] C.H. Lee, J.S. Wang, V.K. Kayatsha, J.Y. Huang, Y.K. Yap, Nanotechnology 19 (2008) 455605. [34] R. Arenal, A. Ferrari, S. Reich, L. Wirtz, J.-Y. Mevellec, S. Lefrant, A. Rubio, A. Loiseau, Nano Lett. 6 (2006) 1812–1816.

© Copyright 2026