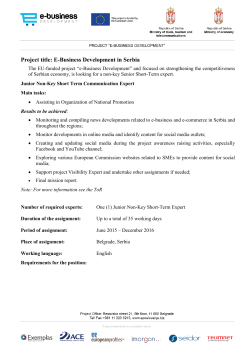

UNDG