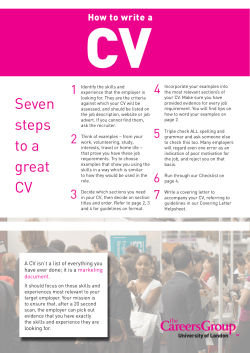

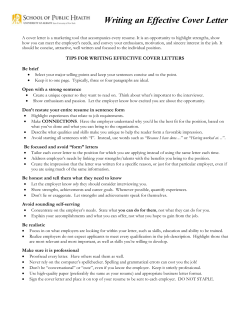

Document 168106