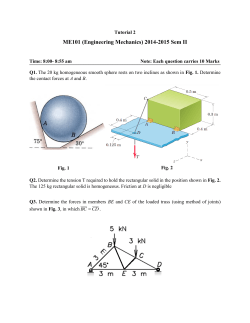

Methods of Analysis and Selected Topics (dc)