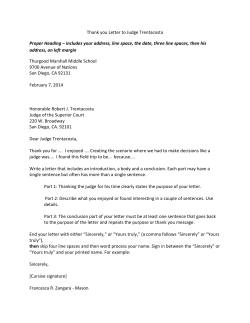

The Circuit Rider