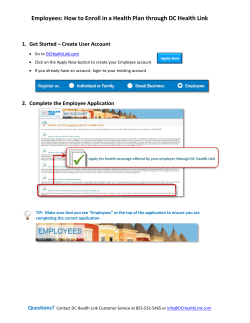

How to obtain more information