HOW TO USE A LEARNING GOAL WORKSHEET TO SUPPORT INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN 8

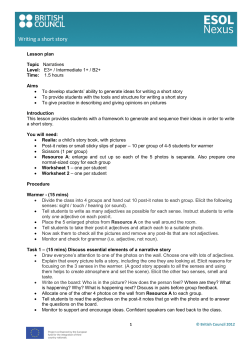

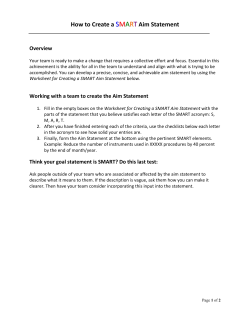

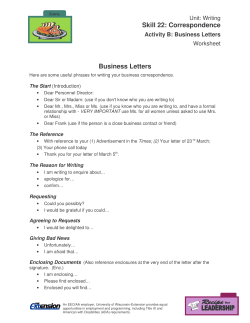

Guide 8 HOW TO USE A LEARNING GOAL WORKSHEET TO SUPPORT INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN Randy Hollandsworth Randy Hollandsworth, PhD serves as director for Radford University’s Center for Leadership and Professional Development in Radford, Virginia. Randy has served as a member and a board member for both the Valleys of Virginia ASTD chapter and the North American Simulation and Gaming Association. Randy worked in executive development with Norfolk Southern Corporation and American Freightways, Inc. He has presented programs on conflict management, communications, leadership, instructional design, and team building for organizations and conferences across the United States. He codesigned a team effectiveness game, TeamSpirit, with Dr. Charles Petranek of the University of Southern Indiana. Randy received his PhD in curriculum and instruction/ instructional technology from Virginia Tech in 2005, with a research emphasis on leadership training design and postinstructional follow-up. Randy is also a frequent contributor to the Sourcebooks. Contact Information: Center for Leadership and Professional Development Radford University’s Business Assistance Center P.O. Box 6953 Radford, VA 24142 540.831.6712 or 540.831.6735 [email protected] www.bac.radford.edu The Learning Goal Worksheet was created to support instructional design for professional training and development initiatives. It serves as a tool to support initial training needs analysis meetings between clients and designer/trainers. The worksheet applies concepts from Gagne’s Learning Outcomes for instructional design (Gagne, Briggs, and Wager, 1988), Kirkpatrick’s Levels of Training Evaluation (Kirkpatrick, 1994), and Gagne et al. (1988) writing effective performance-learning objectives. The Learning Goal Worksheet also serves to document needs, structure learning, and fully define the stakeholder’s learning outcomes 217 for any training initiative. Furthermore, the worksheet provides a template to develop good performance learning objectives for the new or seasoned instructional designer. This tool supports the classic instructional design approach with assessment, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (ADDIE). The information defined in the Learning Goal Worksheet serves as a compass for development, implementation, and assessment, ensuring alignment with the “true” learning goals for the client or key stakeholder. This guide provides an outline for using the Learning Goal Worksheet for assessing training needs and creating performance learning objectives. Defining Learning Goals The resources for defining and writing learning goals are essentially too vast to explore in this guide. However, as a professional designer, trainer, or training manager, you are called on to determine and achieve various learning goals. Theoretically, establishing learning goals falls to the responsibility of whoever is conducting the training needs analysis. The alignment between an effective analysis and defining the learning goals ensures that the correct intervention is applied. The alignment also ensures that needs analysis data involves the client and is not constructed by trainers distanced from the performance. However, in many scenarios, experience has shown that designers and trainers meet with the key stakeholders requesting changes in performance, behavior, or attitude. The Learning Goal Worksheet serves as a reminder for those meetings that maybe training is not the answer to the problem. It also serves as a reminder that learning goals must be broken down into functional performances or skills and that these skills should achieve some level of mastery through various instructional strategies. 218 PRACTICAL GUIDES The use of the Learning Goal Worksheet ensures that these processes are considered and that the initial discussion is documented. In application, define the learning goals documented from a very broad perspective of the performance need. The goal should then be broken down into individual skills or learning performances. For each defined learning goal, a separate Learning Goal Worksheet has to be completed. Defining Levels of Measurement Kirkpatrick’s (1998[AU: or 1994?]) set of measurement classifications have become a standard for the training and development community. The American Society for Training and Development (ASTD) applies these measurement categories into empirical research conducted for the field and ASTD reports on the levels annually. The application of Kirkpatrick’s Levels requires for the purposes of this article requires only a brief review of these categories of measurement: • Level 1 measures perception (class evaluations, focus groups, oneon-one interviews). • Level 2 measures comprehension (practical and written assessments). • Level 3 measures application (observations, self-surveys, 360-degree assessments). • Level 4 measures impact or return (ROI analysis, performance measures). In the Learning Goal Worksheet, a box for Levels of Measurement serves as a reminder to the designer/trainer to engage the key stakeholder in a discussion on what measurement is required early in the design process. GUIDE 8: HOW TO USE A LEARNING GOAL WORKSHEET TO SUPPORT INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN 219 Defining Learning Outcomes Determining learning outcomes, as defined by Gagne, Briggs, and Wager (1988), involves considering hierarchical outcomes applied during the learning event. The key outcomes that are represented by Gagne et al. (1988) are intellectual skills, cognitive strategies, verbal statements, psychomotor skills, and attitudes. The levels of intellectual skill begin with the ability to discriminate between elements at the lowest level, then to identify elements, to demonstrate how to use the elements, to classify the elements, and finally to generate a solution to a problem applying all of the previous intellectual skills (Gagne et al.). Cognitive strategies represent any strategy or tool that supports learning, such as mathematical formulas, conversational models, pneumonic, or other learning aids. Verbal statements represent simple rote learning, such as memorizing key safety rules or customer service center locations. Psychomotor skills reflect more technical performance of skills, such as removing a filter from a machine, replacing a hard drive on a computer, or replicating a shutdown process for a complex computer system. Finally, attitude skills represent seeking to influence an employee’s perception of a new manufacturing process or impacting employee’s attitudes toward customer service. Consider that one learning outcome reflects a single performance learning objective, so checking three boxes of learning outcomes represents three written learning objectives. Experience has shown that the use of the Learning Goal Worksheet serves the designer and developer extremely well but can create confusion with clients or the key stakeholder. Consider that your background in instructional design, in most cases, outweighs that of the stakeholder or subject matter expert. I use the tool to drive design questions and direction of the goals, needs, and how outcomes will appear. However, I limit my involving the stakeholder directly in ISD terminology and concepts both for efficiency and as a courtesy. 220 PRACTICAL GUIDES Writing Effective Performance Learning Objectives A second use for the tool is its ability to support the creation of effective performance learning objectives. This capability of the tool has proven helpful in coaching new designers in writing performance objectives. As defined by Gagne, Briggs, and Wager (1988), performance learning objectives consist of four parts: Performance, Condition, Outcomes, and Criterion. As noted on the Learning Goal Worksheet, reading a specific skill from left to right provides all four parts. The skills are recorded vertically on the Learning Goal Worksheet in the first left-hand column. The second part of a performance learning objective is the condition for learning, or the learning environment. Prior to making this decision, I normally focus on the learning outcomes to determine which outcome is required. As many have found with distance learning, sometimes the technology or medium drives the condition—the opposite of the standard ADDIE approach. Finally, the criterion for learning defines the available learning tools, assessment restrictions, and levels of success or failure in demonstrating comprehension. The Learning Goal Worksheet serves as a template for writing an effective performance learning objective consisting of all four parts. An example of a performance learning objective from the LGW segment is: While performing in dyad and small group role-plays, the participant will demonstrate how to actively listen, with direct feedback provided by participants and the instructor. This objective reflects all four components of a performance learning objective and applies the verbs reflective of a midlevel intellectual skill. Gagne et al. (1988) define specific verbs that highlight the learning outcomes represented: • Intellectual skills: Verbs—discriminates, identifies, demonstrates, classifies, and generates • Cognitive strategies: Verb—adopts • Verbal information: Verb—states • Motor skills: Verb—executes • Attitudes: Verb—chooses Designing with the Learning Goal Worksheet New professionals might seek answers to questions that many of you have already sought, such as, how do I learn more on instructional GUIDE 8: HOW TO USE A LEARNING GOAL WORKSHEET TO SUPPORT INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN 221 design and apply the concepts to my training? The answers are not always easily available except through experience, education, and training. The holistic nature of instructional design and the number of theories and techniques out there provide both the answers and contribute to the confusion. Regardless of the design approach you apply, the use of an instructional systems development (ISD) approach provides systematic and deliberately planned outcomes. It offers controls for instructional strategies and ultimately aligns with the learning goals. Effective instructional design ensures continuity and focus for the designer and the learner. One of the strongest barriers to effective learning is a focus on the process versus the outcomes by designers. This focus may explain some of the low levels of measurement and program follow-up performed by many organizations. The ASTD Annual Report states that surveyed organizations conduct Level 1 measures at 91 percent, Level 2 at 36 percent, Level 3 at 17 percent, and Level 4 at 9 percent (Thompson, Koon, Woodwell, and Beauvais, 2003, p. 32). My hope is that the Learning Goal Worksheet will help shift that focus from the process to learning outcomes. The Learning Goal Worksheet offers fundamental support to a complex process for complex learners. It initiates customer involvement and applies validated theories and tools. The tool offers documentation for the inevitable “returning to the blackboard” that is sometimes required. Finally, it supports the most fundamental instructional design question, how do I best prepare learners to successfully meet the established learning objectives? REFERENCES Gagne, R. M., Briggs, L. J., and Wager, W. W. Principles of Instructional Design, 3rd ed. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1988. Kirkpatrick, D. L. Evaluating Training Programs. The Four Levels. BerrettKoehler Organizational Performance Series. San Francisco, CA: BerretKoehler, 1994. Thompson, C., Koon, E., Woodwell, W., and Beauvais, J. (2003). Training for the Next Economy: An ASTD State of the Industry Report on Trends in Employer-Provided Training in the United States. www.astd.org (accessed August 21, 2003). [AU: Excluded second image of worksheet, same as on page 219] 222 PRACTICAL GUIDES

© Copyright 2026