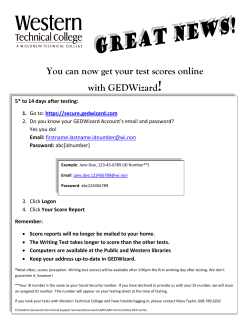

C S P