Stefan Thomas, University of Augsburg, Germany Corresponding author:

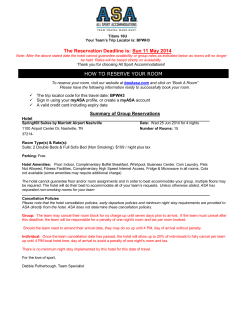

PAY WHAT YOU WANT: HOW TO AFFECT THE PRICE CONSUMERS ARE WILLING TO PAY Stefan Thomas, University of Augsburg, Germany Heribert Gierl, University of Augsburg, Germany Corresponding author: Heribert Gierl University of Augsburg Department of Marketing Universitaetsstrasse 16 86159 Augsburg Email: [email protected] Phone: +49 821-598 4051 Fax: +49 821-598 4216 Abstract: Recently, some studies compared the revenues from regular prices to the revenues from paywhat-you-want pricing and found mixed results. Because pay-what-you-want pricing campaigns can be accompanied by additional information, the question arises about what information can make pay-what-you-want pricing more profitable by increasing customers’ willingness to pay. We investigated the effect of reference prices (i.e., information about the obligatory minimum price or the price customers pay on average) and found that companies should refrain from communicating such reference prices. Moreover, we investigated whether nonprofit organizations benefit more from using pay-what-you-want pricing than profitoriented companies and found no effect. The authors wish to thank Michael Burek, Ebru Coskun, Tobias Dippner, Moritz Dittmar, Christian Dubil, Martin Halm, Andreas Heindl, Hans-Peter Kollmann, Antonia Kraus, Frederik Lotze, Elisabeth Rothemel, Janine Schäfer, Rebekka Steldinger, Charlotte Stiglmayr, Maximilian Tiso and Lars Uhl for helping us collecting the data. The authors would also like to thank the Research Center Global Business Management for the financial support. 1 PAY WHAT YOU WANT: HOW TO AFFECT THE PRICE CONSUMERS ARE WILLING TO PAY ABSTRACT Recently, some studies compared the revenues from regular prices to the revenues from paywhat-you-want pricing and found mixed results. Because pay-what-you-want pricing campaigns can be accompanied by additional information, the question arises about what information can make pay-what-you-want pricing more profitable by increasing customers’ willingness to pay. We investigated the effect of reference prices (i.e., information about the obligatory minimum price or the price customers pay on average) and found that companies should refrain from communicating such reference prices. Moreover, we investigated whether nonprofit organizations benefit more from using pay-what-you-want pricing than profitoriented companies and found no effect. INTRODUCTION The example of the online album “In Rainbows” of the pop artists Radiohead became a famous case of pay-what-you-want pricing. El Harbi, Grolleau, and Bekir (2011) report that 62% of downloaders did not pay anything for the album, 17% paid less than $ 4, 6% paid between $ 4.01 and $ 8, 12% paid between $ 8.01 and $ 12, and 4% paid between $ 12.01 and $ 20. Although the number of downloads is not indicated, the revenue probably was rather high. In this case, the costs per unit (i.e., download) were extremely low and each customer who paid any price directly increased profits. The same effect results when zoos, museums, operas, or football stadiums use pay-what-you-want pricing as long as these facilities do not operate at full capacity. In other cases, when each customer causes additional costs (e.g., customers of a restaurant or a hotel), inviting customers to pay what they want is a risky measure. In Figure 1, we show some examples of advertisements used to promote pay-what-you-want pricing. Prior research in the field of pay-what-you-want pricing mainly focused on the revenues and the profits resulting from pay-what-you-want prices compared to regular prices. The studies provided mixed results. From these findings, we conclude that additional information may be helpful to make pay-what-you-want pricing (more) profitable. In our study, we investigate the effectiveness of two measures. First, we analyze the effect of providing information about a reference price (i.e., an obligatory minimum price or the price most customers actually pay for the product or service) on the willingness to pay and, thereby, on the price customers actually pay in pay-what-you-want conditions. Second, we investigate whether pay-want-youwant pricing is more effective for nonprofit organizations compared to profit-oriented companies. FINDINGS FROM PRIOR RESEARCH In this section, we summarize findings from prior research that compared consumer responses to regular prices to their responses to pay-what-you want pricing. Comparing revenues resulting from regular prices versus pay-what-you-want prices A first stream of research varied the price schema and investigated its effect on units sold, revenues, and profits in real-world settings (Kim, Natter, and Spann, 2009; Gneezy et al., 2 2010; Gneezy et al., 2012; Kim, Kaufmann, and Stegemann, 2013). The findings of these studies are summarized in Table 1. Kim, Natter, and Spann (2009) considered a restaurant, a cinema, and a shop that offers hot beverages. The authors assessed the units sold (i.e., the meals, the tickets, and the cups of hot beverages) in both pricing conditions. They found mixed results. In the case of the cinema, pay-what-you-want prices reduced revenues dramatically (-50%). For the hot beverages, there was no effect, and for the meals, a remarkable increase of revenue due to the pay-what-you-want pricing (+32%) was revealed. In a replication study, Kim, Kaufmann, and Stegemann (2013) considered a restaurant and a cafeteria offering sandwiches and found that consumers paid less in the pay-what-you-want condition compared to the regular-price condition for high-price meals and for the sandwiches. Unfortunately, they did not report the units sold. Gneezy and colleagues (2010, 2012) analyzed the response of consumers to the offer of a photographer to buy a photo of oneself in an amusement park and on a boat tour, respectively, and varied the offered price (regular price vs. pay what you want). For the photo taken in an amusement park, the pay-want-you-want offer reduced the paid price dramatically from the regular price of $ 12.95 to $ 0.92 while the units sold strongly increased from 141 to 2,365 within a two-day period. However, despite this increase of units sold, the pay-what-you-want price turned out to be disadvantageous because the costs per unit equaled the average price paid ($ 0.92) and, thus, profits were zero. For the case of the photo taken on a boat tour, the regular price and the pay-what-you-want price resulted in the same amount of revenues. Moreover, Gneezy et al. (2012) found that promising that half of the price will be donated to a charity organization is an effective measure for increasing profits in the pay-what-you-want condition. Comparing prices paid in pay-what-you-want environments depending on the payment mode and additional price information There are also studies that compared the real price paid under different pay-what-you-want conditions in real-world settings (see Table 2). First, the mode of payment (face-to-face to the staff or anonymous payment) was varied expecting that payments are higher in the face-toface condition due to the lower social distance to the staff. Second, the authors analyzed the effect of additional pieces of price information (e.g., the availability of the price that is paid on average). We should note that the studies of Kim and her colleagues also had varied these factors; however, they did not provide detailed results. For a restaurant, Gneezy et al. (2012) found that customers paid less for the ordered meals in the face-to-face condition compared to the condition of anonymous payment which contradicts expectations. For a coffee drink, Jang and Chu (2012) showed that the average price consumers actually pay is lower when they get the information that most of the customers did not pay for the product compared to the condition in which the consumers were informed that most of the customers paid more than the unit costs of the product. This finding indicates that consumers take information about other customers’ payments into account when deciding about the price they actually pay. Effect of reference prices on the willingness to pay in pay-what-you-want settings Using a laboratory setting, Johnson and Peng Cui (2013) investigated the effects of the presence of reference prices (e.g., the information about an obligatory minimum price or the information about what most of the customers pay) on the willingness to pay. However, their findings were rather inconsistent and, thus, are not suitable to gain insights into the effect of reference prices on willingness-to-pay and, as a consequence, on the price paid in pay-whatyou-want environments. 3 HYPOTHESES Reference prices Following the ideas of Johnson and Peng Cui (2013), we investigate the effect of providing reference-price information in the context of pay-what-you-want pricing. First, information about a (low) obligatory minimum price could be given by the company. Referring to the approach of the anchoring and adjustment heuristic (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974), we presume that this piece of information serves as an anchor and the price consumers are willing to pay is adjusted to this low anchor. We test: H1a: Consumers’ willingness to pay in a pay-what-you-want setting is lower if a minimum price is provided compared to the condition where this information is absent. Second, information about what customers pay on average can be provided. We presume that the willingness to pay is also assimilated to this kind of reference price. Because the minimum price is lower than the average price, we hypothesize: H1b: Consumers’ willingness to pay in a pay-what-you-want setting is lower if a minimum price is provided compared to the condition where the price customers pay on average is given. Profit versus nonprofit orientation Gneezy et al. (2010) found that consumers’ payment in a pay-what-you-want setting was much higher when the purchasers could support a charitable organization. Referring to this finding we expect that the willingness to pay is higher under nonprofit conditions and test: H2: Consumers’ willingness to pay in a pay-what-you-want setting is higher if the seller is nonprofit oriented compared to profit-oriented sellers. EXPERIMENT We assessed the willingness to pay in a laboratory setting and used this measure as the dependent variable. As experimental factors, we used the reference-price information and the profit orientation of the seller. Our experiment is based on a 2 (perspective) × 3 (reference-price information) × 3 (profit orientation) between subjects × 2 (service category) within subjects design. Service category. As a first factor, we considered the service category (pizza restaurant/delivery service and hotel double bedroom). Self/other perspective. Kim, Kaufmann and Stegemann (2013) found that the willingness to pay differs from the price consumers actually pay in a pay-what-you-want environment. When consumers were asked to indicate the price they were willing to pay they indicated higher prices than they actually paid. The deviations ranged from 9% to 25% (see Table 3). Probably this finding is due to the phenomenon of the social desirability bias. Hence, we included a second factor in the experimental design by varying the self/other perspective. In the self-perspective, the test participants were asked to indicate their own willingness to pay, and 4 in the other-perspective, they were asked to estimate the price their friends are willing to pay. We consider both perspectives when the effects of the experimental factors are tested. Manipulation of the experimental factors. The third factor, reference-price information, was varied in three levels (no reference price; obligatory minimum price; and information about what customers pay on average). The fourth factor, the company’s profit orientation, was also varied in three levels. In the case of the pizza, we considered one type of nonprofit- and two types of profit-oriented sellers; in the case of the hotel accommodation, we included two types of nonprofit hotels and one type of a profit-oriented hotel. Procedure. We used a student sample to investigate the effect of the experimental factors on the willingness to pay in pay-want-you-want scenarios. According to the experimental design explained above, each test participant was randomly exposed to one of 18 scenarios describing the purchase of two pizzas and to one of 18 scenarios describing hotel accommodations. The text elements used to describe the scenarios in the case of the pizzas are listed below. Imagine you want to eat a pizza with a friend. In your town, there is a new pizzeria. It is run by handicapped people and volunteers. All profits are going to a project that contributes to enable assisted living for mentally handicapped people. [nonprofit pizzeria] In your town, there is a new pizzeria. It is just around the corner, family-owned, and with a very personal atmosphere. You know the owner and some of the waiters. [profit-oriented pizzeria] In your town, there is a new pizza delivery service which has sent you the menu. You decide to order pizza. [profit-oriented pizza delivery service] You invite your friend and order one pizza with ham and one pizza margherita. The menu does not contain prices. The staff informs you that you can choose the price that you want to pay. The menu does only contain minimum prices. For a pizza with ham, the minimal price is € 2.00, and for a pizza margherita, it is € 1.70. This staff informs you that you can choose your own price; the prices indicated on the menu are only covering the pizzeria’s operating costs. The menu does not contain prices. While ordering the staff informs you that you can choose the price that you want to pay, however, they mention that most customers are paying € 6.00 for a standard pizza. You and your friend are very satisfied with the service and the dish. Please indicate the price that you are willing to pay for both pizzas. Please indicate the price most of your friends would pay for both pizzas. The same technique was used for creating 18 scenarios for the hotel accommodation. To manipulate the profit orientation, we considered a nonprofit hotel and a nonprofit youth hostel and a profit-oriented “design hotel”. The “design hotel” was described as a hotel with modern and stylish interior. The obligatory minimum prices were € 17 for the nonprofit hotel, € 12 for the nonprofit youth hostel, and € 34 for the design hotel. The information about the price that customers pay on average was € 50, € 35, and € 100, respectively. After reading one scenario, each test person either had to indicate his/her own or to estimate his/her friends’ willingness to pay. Sample. 16 student interviewers helped us collecting data from 570 students (48.2% female students, Mage = 24.29, SD = 3.001). Thus, there are approximately 31.7 test persons per experimental condition. Data were collected face-to-face at a German university in 2013. Results. We report the findings for the willingness to pay depending on the service category, the self/other perspective, the information about the reference price, and the profit orientation of the company in Table 4 and Table 5. Table 4 contains the mean values of the willingness to pay. Because this scale’s upper end is not limited, the mean values are outlier-sensitive. Thus, 5 we also calculated the median values for the willingness to pay and show these findings in Table 5. Test of H1a. We postulated that the information about an obligatory (low) minimum price reduces the willingness to pay. When information about the minimum price was absent, the average willingness to pay was € 14.99 (two pizzas) and € 58.19 (hotel). When providing the minimum price of € 3.70 (two pizzas) or a low price for the hotel accommodation (between € 12 and € 34), the average willingness to pay was reduced to from € 14.99 to € 9.73 (t206 = 7.968, p <.001) for the pizzas and from € 58.19 to € 35.04 (t208 = 5.605, p < .001) for the hotel accommodation in the self-perspective condition. The same pattern of results was found for the other-perspective and when the median values were compared instead of comparing mean values. The findings provide support to H1a. Test of H1b. Next, we expected that the information about the price which is paid on average results in higher prices consumers are willing to pay compared to the information about a lower obligatory minimum price. For the pizzas, the willingness to pay was higher in the average-price condition compared to the minimum-price condition (€ 12.23 > € 9.73, t208 = 4.766, p < .001). The same effect was observed for the hotel accommodation (€ 54.86 > € 35.04, t209 = 6.174, p < .001) in the case of asking the test participants to indicate their own willingness to pay. For the other-perspective the same pattern of results was observed. In sum, the findings are also in line with H1b. Test of H2. We expected that the willingness to pay in a pay-what-you-want scenario is higher for a product or a service from a nonprofit seller compared to products and services from profit-oriented companies. For the pizzas, we held products (a pizza margherita and a pizza with ham) constant across the profit-orientation conditions (i.e., the nonprofit pizzeria, the profit-oriented pizzeria around the corner, and the profit-oriented pizza delivery service). Thus, the results for these conditions are most suitable for testing H2. Interestingly, the findings depend on the self/other-perspective. In the self-perspective, the average willingness to pay for the pizzas from the nonprofit pizzeria was € 18.11 which exceeded the willingness to pay for pizzas from the profit-oriented companies (€ 18.11 > € 14.88, t66 = 2.405, p < .05; € 18.11 > € 11.97, t68 = 4.781, p < .001). However, when the test participants put themselves in their friends’ perspective, the effect of the profit orientation disappeared (nonprofit: € 10.54, profit-oriented: € 11.61 and € 11.09, F2; 83 = .731, p > .40). These findings indicate that higher values of one’s willingness to pay for products and services from nonprofit sellers that use pay-what-you-want pricing may result only from the social desirability effect of answers provided in questionnaires. Our findings awake doubts about the presumption that the profit orientation actually reduces consumers’ willingness to pay. Therefore, we reject H2. IMPLICATIONS FOR ADVERTISING PRACTICE Our findings show that companies which decided to use pay-what-you-want pricing should refrain from asking for low obligatory minimum prices or providing information about the price consumers pay on average if this price is comparatively low. Moreover, our analysis does not provide evidence to the presumption that this pricing technique is more effective for nonprofit organizations than for profit-oriented companies. Marketers simply should inform that customers can pay what they want. Additional information about reference prices should be avoided when pay-what-you-want campaigns are announced. 6 TABLES AND FIGURES Table 1: Results on the effect of regular vs. pay-what-you-want pricing on units sold and revenues Authors Regular price Price Units sold Kim, Natter, Meal in a restaurant € 7.99 157 and Spann Multiplex cinema € 6.81 394 2009 Hot beverages € 1.75 872 Kim, Kaufmann, and Stegemann 2013 Service Low-price meals € 4.29 Medium-price meals € 7.84 High-price meals € 12.40 Sandwich € 1.50 Revenue € 1,254 € 2,681 € 1,529 Pay what you want Payment Additional price mode information FtF none FtF RP FtF RP or none Average Units price sold € 6.44 253 € 4.87 273 € 1.94 813 FtF or anon FtF or anon FtF or anon FtF or anon € 4.20 € 7.63 € 10.29 € 1.19 RP or none RP or none RP or none RP or none Revenue € 1,660 € 1,329 € 1,577 Gneezy et Photo in an $ 12.95 141 $ 1,823 FtF none $ 0.92 2,365 $ 2,176 al., 2010 amusement park $ 12.95 180* $ 2,331* $ 5.33* 1,168* $ 6,224* $ 3.2×N Gneezy et Photo on a boat tour $ 5 64%×N FtF none $ 6.43 55%×N $ 3.5×N al., 2012 23%×N $ 3.4×N $ 15 Notes. FtF: payment of the customer face-to-face to the waiter, Anon: payment can happen anonymously. RP: information about the regular price was available to the customers. N: Number of the participants of the boat tour. * Results when the photographer promised to donate 50% of the price to a charity organization. Table 2: Results on the effect of payment mode and additional piece of price information on the price paid in real-world pay-what-you-want environments Authors Service Gneezy et Restaurant al., 2012 Jang and Coffee Chu 2012 drink Payment mode Face-to-face Face-to-face Anonymously Anonymously Anonymously Anonymously Anonymously Additional price information none “on average, customers pay € 6” none “on average, customers pay € 6” “unit costs are $ 0.25” “unit costs are $ 0.25 but 72% pay nothing” “72% paid more than the units costs of $ 0.25” Average price paid € 4.66 € 5.44 € 5.37 € 5.20 $ 0.37 $ 0.30 $ 0.42 Table 3: Comparison of the willingness to pay and the price paid in real-world pay-what-youwant environments Willingness to pay assessed in questionnaires Restaurant Low-price meals € 4.71 Medium-price meals € 8.61 High-price meals € 11.18 Cafeteria Sandwich € 1.49 Source: Kim, Kaufmann, and Stegemann (2013) Average price actually paid in the paywhat-you want condition € 4.20 € 7.63 € 10.29 € 1.19 7 Table 4: Mean values of the willingness to pay in € depending on price information and the self/other-perspective Nonprofit pizzeria Own willingness to pay No price Information informati- about the on minimum price 18.11 11.25 (MP = 3.70) Information about the average price 13.53 (AP = 12) Estimated willingness to pay of friends No price Information Information information about the about the minimum average price price 10.54 7.44 6.34 (MP = 3.70) (AP = 12) Pizzeria around the corner 14.88 8.07 (MP = 3.70) 12.34 (AP = 12) 11.61 7.79 (MP = 3.70) 8.93 (AP = 12) Pizza delivery service 11.97 9.87 (MP = 3.70) 10.81 (AP = 12) 11.09 6.03 (MP = 3.70) 11.17 (AP = 12) Overall 14.99 9.73 (MP = 3.70) 12.23 (AP = 12) 11.03 7.20 (MP = 3.70) 8.48 (AP = 12) Nonprofit hotel 57.46 30.23 (MP = 17) 51.64 (AP = 50) 74.14 42.38 (MP = 17) 46.86 (AP = 50) Nonprofit youth hostel 40.76 24.72 (MP = 12) 33.51 (AP = 35) 36.04 20.93 (MP = 12) 35.82 (AP = 35) Design hotel 75.86 50.46 (MP = 34) 79.43 (AP = 100) 75.61 44.00 (MP = 34) 85.26 (AP = 100) Overall 58.19 35.04 54.86 62.13 35.55 53.53 Notes: MP = given obligatory minimum price; AP: given price that is paid by customers on average. Table 5: Median values of the willingness to pay in € depending on price information and the self/other-perspective Nonprofit pizzeria Own willingness to pay No price Information informati- about the on minimum price 17 10 (MP = 3.70) Information about the average price 14 (AP = 12) Estimated willingness to pay of friends No price Information Information information about the about the minimum average price price 10 5 6 (MP = 3.70) (AP = 12) Pizzeria around the corner 15 6 (MP = 3.70) 13 (AP = 12) 12 6 (MP = 3.70) 7 (AP = 12) Pizza delivery service 12 10 (MP = 3.70) 12 (AP = 12) 11 5 (MP = 3.70) 12 (AP = 12) Overall 15 10 (MP = 3.70) 13 (AP = 12) 12 6 (MP = 3.70) 7 (AP = 12) Nonprofit hotel 60 25 (MP = 17) 50 (AP = 50) 75 35 (MP = 17) 50 (AP = 50) Nonprofit youth hostel 40 15 (MP = 12) 35 (AP = 35) 40 20 (MP = 12) 35 (AP = 35) Design hotel 70 50 (MP = 34) 80 (AP = 100) 60 40 (MP = 34) 90 (AP = 100) Overall 50 34 50 50 35 45 Notes: MP = given obligatory minimum price; AP: given price that is paid by customers on average. 8 Pay-what-you-want offer for an accommodation in a hotel Pay-what-you-want offer Pay-what-you-want offer for for a visit of a zoo a meal in a restaurant Figure 1: Real-word examples of advertisements promoting pay-what-you-want pricing 9 REFERENCES El Harbi, S., Grolleau, G., Bekir, I. (2011). Substituting piracy with a pay-what-you-want option: Does it make sense? European Journal of Law and Economics, doi: 10.1007/s10657-011-9287-y. Gneezy, A., Gneezy, U., Nelson, L. D., Brown, A. (2010). Shared social responsibility: A field experiment in pay-what-you-want pricing and charitable giving, Science, 329(5989), 325-327. Gneezy, A., Gneezy, U., Riener, G., Nelson, L. D. (2012). Pay-what-you-want, identity, and self-signaling in markets, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120893109 Jang, H., Chu, W. (2012). Are consumers acting fairly toward companies? An examination of pay-what-you-want pricing, Journal of Macromarketing, 32(4), 348-360. Johnson, J. W., Peng Cui, A. (2013). To influence or not to influence: External reference price strategies in pay-what-you-want pricing, Journal of Business Research, 66(2), 275-281. Kim, J.-Y., Kaufmann, K., Stegemann, M. (2013). The impact of buyer-seller relationships and reference prices on the effectiveness of the pay what you want pricing mechanism, Marketing Letters, forthcoming, DOI 10.1007/s11002-013-9261-2 Kim, J.-Y., Natter, M., Spann, M. (2009). Pay what you want: A new participative pricing mechanism, Journal of Marketing, 73(1), 44-58. Tversky, A., Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases, Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.

© Copyright 2026