How to Summarize and Synthesize Research Reports A Handbook

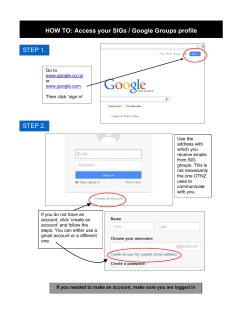

How to Summarize and Synthesize Research Reports for use in Policy Decision-Making A Handbook Prepared by: Nadine Wathen & Gillian Watson For the Women’s Health Unit Ontario Ministry of Health & Long-Term Care May 2007 Running Head: Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Background 2 Context 2 Problem 2 Solution 2 Purpose of this document 2 Figure 1: Overview of the Process 3 Step One: Identify Topics & Set Priorities 4 Step Two: Identify End Users & Their Needs 5 Step Three: Develop Data Collection Tools 7 Step Four: Data Extraction, phase one 9 Step Five: Data Extraction, phase two - Develop Draft Summaries 10 Step Six: Research and Literature Update 12 Step Seven: Product Design & Completion Incorporating User Feedback 13 Step Eight: Dissemination 15 Step Nine: Maintenance and Updating 16 Appendix 1: OWHC KT Project - Priority-Setting Survey Tool 17 Appendix 2: OWHC KT Project – User Focus Group Guide 21 Appendix 3: OWHC KT Project – Sample Interview Guide 24 Appendix 4: OWHC KT Project - Content Extraction Tool 25 -1- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Background Context Accessing and using evidence-based research is a goal of the health care system and health policy decision-makers. • Government and non-government organizations expend significant resources commissioning and conducting research and development projects that lead to large paper-based reports. Problem Shelves filled with paper-based reports and documents that are inaccessible and/or unused. Even when available online, these reports are often unused due to length, format and reporting style. Solution Short, user-friendly information products that provide key messages and… … are based on an understanding of end user needs and work contexts, … are designed according to these needs, … help users find, understand and implement the evidence in their daily decisions, … are made available in easy-to access formats and places, both print and electronic. Purpose of this document To provide a step-by-step guide to converting program evaluation and research findings into user-friendly and accessible policy-oriented summaries. The process description will use the example of the Ontario Women’s Health Council (OWHC) Knowledge Translation (KT) Project, which developed brief, accessible lay summaries, designed with and by end users on: • seven content-specific topics in women’s health, and • two program processes and ‘lessons learned’ The overall project period was 9 months; estimated times for each step are provided, and some steps took place concurrently. -2- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Figure 1: Overview of the Process Step 1: Identify topics & set priorities Step 2: Identify users & their needs Step 3: Develop tools to extract relevant information from the reports Step 4: Extract key information from reports and related documents Step 6: Search for new information on topic Step 5: Draft summary incorporating: report data, user needs and new information Step 7: Product design incorporating feedback from end users (e- and print versions) Step 8: Disseminate summaries to users (strategies for electronic and paper delivery) Step 9: Maintain and update summaries (as required) -3- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step One: Identify Topics & Set Priorities In cases where there are too many topics to feasibly synthesize, a topic identification and priority setting stage is essential. Depending on time and resources, this step is needed to determine what topics should be considered – on the basis, for example, of the quality and/or importance of the evidence provided - for further development, and prioritize amongst them. One way to prioritize the topics is to conduct a survey with available experts using a purpose-designed survey tool (e.g., Appendix 1). Experts selected for consultation will depend on the project’s interest group, and may include some or all of: research sponsors/funders; end users; external experts or others with an interest/stake in the process. The results of the survey are collated to determine the main topics to be included in the knowledge synthesis and product development process. Alternate methods to identify priority topics include letting the funders or sponsors decide, or basing the decision on other factors, such as internal priorities, feasibility, or resources. The OWHC KT Project Experience: The OWHC (“council”) funded a broad spectrum of women’s health research which resulted in findings of relevance to clinical and policy decision-makers in Ontario and beyond. More than 75 completed reports, as well as numerous projects and programs covering a broad range of topics, were available to translate into policy-oriented documents. However, it was not feasible to synthesize this many topics for the KT project. Therefore, a systematic process of topic identification and priority setting took place as follows: 1) A table of topics and related documentation was prepared. 2) A process for surveying current and former council members was developed, including a data collection tool (Appendix 1). 3) Members of council completed the survey and the results were collated to determine the 6-7 main topic areas to be included in the knowledge synthesis and product development process. Of the topics selected, two were deemed to be process-related (i.e. providing valuable “lessons learned” regarding implementation of specific activities of council) while the others provided specific research findings of interest to potential users. Estimated time for this step: The table of completed topics and related documentation stage took approximately 1 day to complete. The priority setting stage took three to four months to survey eleven current and former council members, to tabulate results and to have council formally ratify the priority topics. -4- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Two: Identify End Users & Their Needs To ensure that that the products created are maximally relevant and usable to the target audience, it is vital to be clear about who the end users of the products are likely to be, what information they would find most useful, and how they would like to receive the information. How to identify users: The end user is usually determined by the mandate and scope of the project – i.e., those who commissioned the project should be able to advise who the products are for. If this is not clear, consulting with those who initiated the project should help clarify this. How to identify users’ needs: There are several ways to determine user needs. Below are common approaches used to consult end users; the method selected will depend on specific project goals and available resources. Consulting existing literature: There may be published tools and guides for developing knowledge products for specific audiences. For example, the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF) offers helpful tips on how to create different end products for different policy-specific uses, including: • a 1-page summary for the bottom-line messages • a more detailed 3-page summary, and • a comprehensive 25 page document for those requiring more detail Tip: See the CHSRF KEYS for more information on providing research evidence to policy audiences: http://www.chsrf.ca/keys/index_e.php Informal discussions: An important part of knowledge translation is building relationships between those providing the research information and end users. Starting informal discussions with end users at any point in the development process (but the earlier the better!) will make the end product more useful. Focus groups: The primary purpose of an initial focus group is to understand exactly what users expect and want from the product that is being created. It is also an excellent opportunity to explain what the project is about, introduce the knowledge translation process, and make users aware that the products are under development for them. The following should be included: • participants who represent the end users; • an expert facilitator guiding discussion and a project representative available to introduce the project and provide clarification or additional detail about content or process; • a draft approach for extracting, summarizing and synthesizing the available information; • an outline of various options for the look and feel of the end products. -5- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Formal interviews: Formal interviews with experts in the field or with key representatives of the end user group may be useful to have to gain insight on specific aspects of the knowledge or its use not captured in the focus group (for example, any political or other less obvious consequences of the work). Individual interviews might target end users at a “higher” level than would the focus groups. The OWHC KT Project Experience: Identification of end users: the target group was determined by the OWHC to be policy personnel (manager and analyst levels) in the Ministry of Health & Long Term Care and other provincial ministries as appropriate. Identification of user needs: these were determined by informal discussions, formal interviews and focus groups with end users; review of available literature on knowledge translation and research dissemination; and consultation with experts in this area. The focus group guide is found in Appendix 2. Estimated time for this step: The identification of end users was determined through discussion at a meeting with council. The process for identifying user needs took approximately three months, and included a review of current knowledge translation literature, several informal discussions, two focus groups, and two formal interviews. -6- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Three: Develop Data Collection Tools Once end user needs are identified, the next step is to develop and refine the data collection tools. There are several ways to extract or collect information from projects according to project type. If it is a process topic, a useful way to gather, understand and synthesize “lessons learned” is to conduct interviews with key informants who were involved with the implementation of the project/ program being described. If the topic is content or results-oriented, the main data collection approach is a content extraction tool to guide the selection of pertinent content/data from the research reports. Interview Guides Key informants to consult regarding a process topic are ideally the main report author(s), and/or the program/project lead (depending upon the type of process involved). A semi-structured interview guide, with several probes regarding the project’s main process and outcome-related accomplishments and shortcomings should be used. The goal of these interviews is to determine the best practices that could be applied by those attempting to develop and implement similar programs or projects, and what practices should be avoided. Content Extraction Tool A key step in developing the content that will ultimately be synthesized into the knowledge product(s) is to determine what to extract from the existing reports. The following are tips to developing a useful content extraction framework: • If there are a series of reports, they should be reviewed to get an idea of the different sections available for extraction. • Design an initial draft with what to extract from each section. Someone familiar with the general content and structure of the reports should review this initial draft. • Test the initial content extraction tool by extracting information from one of the documents to see if it includes all of the sections and necessary data. • Present the draft framework at the initial end user focus group; incorporate changes suggested by participants. -7- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports The OWHC KT Project Experience: Development of interview guide: The OWHC KT project had two processrelated topics. In consultation with OWHC staff, it was determined that the best approach for collecting and documenting this information was to conduct in-depth interviews with some of those closely involved with the topics. Interview guides were created for each topic and are attached in Appendix 3. Development of content extraction tool: The same content extraction tool was used for both process and content-specific research summaries. A draft of this was reviewed at the end-user focus groups to ensure that all required information was included. The final content extraction tool can be found in Appendix 4. Estimated time for this step: The development of both the interview guide and content extraction tool took approximately three weeks. -8- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Four: Data Extraction, phase one Once the data collection tools have been created and refined, the next step is to conduct the interviews and extract the content from the reports. Interviews: There is no initial stage of data extraction from the interview notes. Content extraction: At this stage it is important to be very inclusive to avoid excluding potentially valuable information. At the end of the first extraction phase it is possible to have many more pages of information than will ultimately be included in the final summary. Since the reports can be lengthy, the first phase of data extraction may be somewhat time consuming, and time and resources should be allocated accordingly. Here are some tips that can guide the data extraction phase: • Read the executive summary first and extract the necessary information based on the content extraction tool. If there is insufficient information in the executive summary, the full text must be reviewed. • Often it is not necessary to read the details of the results section. This is because the most significant results will be summarized at a higher level in the discussion – ideally in the form of key messages or findings. • If the executive summary does not provide sufficient information on study implementation, then the methods section must be reviewed to understand the procedures used, and, importantly, the population to which the findings can (or cannot) be generalized. • The discussion and conclusion are key places to find the most important results and their implications. • It is useful to write down the page number of the extracted information, in case further clarification of any of the information extracted during the next step is required. The OWHC KT Project Experience: Due to the length of the reports, the initial content extraction phase in the OWHC KT Project was one of the more time consuming phases. The most challenging part of this process was finding the most relevant main findings and conclusions. Some of the reports included most of the required information in the executive summary, whereas others required reading most or all of the discussion and conclusion sections to understand the main findings related to women’s health. Estimated time for this step: The duration of data extraction ranged depending on the length of the reports. For example, if a report was 200 pages long, this process took approximately 4-6 hours. -9- Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Five: Data Extraction, phase two - Develop Draft Summaries The development of the initial draft capsules should include the sections that were suggested by end users. This process is highly iterative and allocating sufficient time for rounds of refinement and editing is recommended. Interviews: After completion of the interviews, the notes should be sent back to the interviewees for any additional comments and clarifications. The content for the initial draft of the process-oriented summaries should come from the interview notes. If there is more than one interview conducted, go through the interview notes and find all the similarities. The similarities in the key lessons learned should be emphasized. Content extraction: Essentially, drafting the initial summary document is the second stage of data extraction, but this time from a much smaller amount of data (the content extracted in phase one). At this stage more than one report could be included in the summary if the topics are related. Useful tips include: • Put as much information as possible in bullet points rather than narrative paragraphs. • When possible, avoid reporting complicated statistics (e.g. p-values, t-test results, etc. that may be meaningless to those without a research background), rather use percentages or simple descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations and odds ratios. • When preparing more than one summary, keep the look and feel consistent, for example through the use of similar headings, especially if the end products will be distributed as a “package.” • Use lay rather than technical language; avoid jargon and acronyms. • Include a section on ‘how to cite’ the document, and who the summary authors are. • Include the author of the original report and their contact information. Prior to doing this, the report author should be given the opportunity to review the material and permission obtained to include their name and contact information. • Include information on how to access the full report(s) and any other materials that were used or cited to prepare the summary. - 10 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports The OWHC KT Project Experience: There were two types of drafts made for this project, one for the contentoriented summaries and the other for the process-oriented summaries. The process-oriented drafts were developed based on information from the interviews. Estimated time for this step: The length of time it took to extract information from the phase one extraction file into an initial draft summary depended on the number of reports being combined. A summary that included one report took approximately three hours, whereas a summary that combined more than one report took up to eight hours. The revisions at this stage took 2-3 weeks depending on how many people were editing the draft. - 11 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Six: Research and Literature Update Depending on the topic and the time elapsed since project completion, a research and literature update might be required. This is particularly true in cases where: there is more recent research or data on the topic that reinforces or refutes the report(s) being summarized; or there have been related policy or program decisions made on the topic in other jurisdictions (e.g., other provinces) of interest to end users. If there is a significant amount of new information, a professional librarian may need to conduct a comprehensive search. Other ways to determine whether there may be new and relevant information include asking experts in the field, consulting recent policy decisions, or (for a very general overview) conducting an online search using specific keywords. The OWHC KT Project Experience: Several of the summaries may require additional/recent information sections, for example when the report was older and new evidence had emerged since it was released; or to assist in context-setting; provide background or related information, etc. Examples of the types of new information that were included in some of the research summaries are: • new guidelines on a procedure or intervention • information on similar or different new programs started in other provinces or states • links to other more recent evidence-based reviews or reports on a topic • description of policy and practice-related controversies or uncertainties Estimated time for this step: This was an ongoing phase of the development of the capsules, which took place over approximately three months. - 12 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Seven: Product Design & Completion Incorporating User Feedback If budget permits, it is advisable to involve a graphic designer to develop a summary that is visually appealing and easy to read. At the final draft stage of the summary, a series of design and user feedback iterations generally follows and time and resources should be budgeted accordingly. Focus group: A focus group can be used as a form of usability testing once there is a near final draft of the summary. The following steps for the focus group should be included: • Email the draft(s) to participants one week prior to the focus group so that they have a chance to read the summaries and are then prepared to comment on the content and format. • Everything from content to structure to aesthetics should be discussed. • Have an external facilitator run the focus group with a project representative to answer specific topic-related questions; however if budget is a concern, a project representative can probably run it alone. • Every participant should have a colour-printed version of the near final draft of each summary. Final Version: the process of finalizing the summary includes: • incorporating all relevant feedback from end users and report authors • adding any new information retrieved • a round of final text editing by those preparing the summary, and one or two others who have yet to view the product, if possible • professional layout in an appropriate design software package • selection of a professional printer and discussion of colours, logo and final layout between the designer, printer and someone from the summary team. - 13 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports The OWHC KT Project Experience: A focus group was held with the same users consulted in the initial focus group. There were many suggestions for the aesthetics and structure. All of the suggestions that were feasible were included in the final design. Final production of the summaries was conducted by a graphic designer using Adobe InDesign software. Print and e-versions (pdf) were prepared, with careful attention paid to such issues as colour-matching with the OWHC logo, length, layout, etc. Estimated time for this step: The design and user feedback stage took approximately three weeks. Preparing the final versions of the nine summaries took approximately two weeks including final editing and review by the team, layout by the graphic designer for both electronic and print versions, and printing. - 14 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Eight: Dissemination The dissemination strategy will depend on the identity and information seeking patterns of the end users. There are a variety of ways to disseminate the summaries, including: • email the intended users the summaries in portable document format (pdf); and/or • post the summaries on a website with links to the various topics, if more than one. Then email the intended users the web link; and/or • send the print versions of the summaries by mail; and/or • present them at a conference or other relevant venue. The OWHC KT Project Experience: Several methods were used to disseminate the summaries. This project might be unique because the summaries were presented at a farewell reception for the OWHC. They were printed in colour and were two to four pages long. Following this initial release, the pdf versions of the summaries were posted on the OWHC website: http://www.womenshealthcouncil.on.ca/English/Knowledge-TranslationTools.html. They were also sent to an identified end user group including CEOs and Planning Directors of Local Health Integration Networks and community health centres. Estimated time for this step: The dissemination of the summaries took approximately two weeks. - 15 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Step Nine: Maintenance and Updating Whether and how to maintain and update research summaries is something that should be considered as early as possible in the development process, as it will have significant resource implications. An initial decision is whether the project is “one time only” (as was the OWHC KT Project) or is expected to provide “living” summaries. If the project intends to maintain and update summaries, the following issues should be considered: 1) Determine the time-frame for reviewing topics for update. This can be yearly, however the intensity of work in the topic area may dictate more or less frequent reviews. 2) Decide if updates will consist of augmentation of the existing summary with new information only (e.g., “add-on”), significant revision to several sections (e.g. “update”), or complete overhaul of the topic – essentially starting from scratch. The decision will depend on the topic, but having an a priori protocol outlining which factors lead to which decision is helpful. Such factors include: a. the amount of new information; b. the type of new information (i.e., does it support or contradict the previous conclusions); c. new controversies or other contextual factors that may require a different treatment of the issue. 3) Determine who will make decisions regarding whether updating is required and who will conduct the topic reviews. Ideally, some of those who were on the original review and summary team will be part of the updating process. 4) Develop a protocol for how to search for new information (sources, tools, etc.) and how much time will be spent doing this. 5) Decide what will happen in cases where searches for new information yield nothing of note (i.e., nothing that changes the conclusions of the original summary). For example, will the same summary be re-released with a note indicating when it was last checked for new relevant information? The OWHC Knowledge Translation Project Experience: The OWHC KT Project was “one time only” and did not build this step into its process. - 16 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Appendix 1: OWHC KT Project - Priority-Setting Survey Tool Instructions: Please use the information to guide you in assigning a “significance” rating to each of the main topic areas. If an important topic area has been missed, please include it at the end. This is a subjective process, based on your experience with council. “Significance” can include any combination and weighting of criteria including: the breadth of scope of the available work; quantity; quality; how current the work is; how applicable it is to policy; practice and public decision-making, etc. Since it is not feasible to capture each of these criteria separately, we ask that you provide an overall impression of each topic. Your ratings will help council decide the ultimate question: “what 5 or 6 topics are the most significant and valuable contributions that OWHC has made, and should ensure are developed into userbased “knowledge products” and featured as legacy items?” Please rate each topic area by circling the number corresponding to its “significance” on the 5-point scale, where 1 = less significance and 5 = more significance. 1. Maternity Care Reports: Attaining and Maintaining Best Practices in the Use of Caesarean Sections: An analysis of four Ontario hospitals (2000); Caesarean Section Best Practices Project: Impact and Analysis (2002); Maternity Care in Ontario: Emerging Crisis, Emerging Solutions (2006) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 2. Emergency Contraception Projects: ECP through pharmacists (2001); Survey re: ECP availability (2006); Advocacy: ECP public awareness campaign (2006) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 3. Cancer Projects: BRCA testing (2006); HPV testing in primary care (2007); Cervical cancerscreening program recommendations (2006); Report: The Quality of Cancer Services for Women in Ontario (2006) 1 less sig. 2 3 - 17 - 4 5 more sig. Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports 4. Abortion Project: Studies on Access to Abortion Services (2007) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 5. Mental Health Report: A Literature Review of Depression Among Women: Focusing on Ontario (2006) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 6. Building Research Capacity Projects: Endowed chairs, various awards programs, Research days conference 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 7. Women’s Health Reporting Reports: Ontario Women’s Health Status Report (2002); Accountability in Women’s Health (2005); Projects: Hospital Reports and related (various); Project for an Ontario Evidence-Based Report Card (POWER) (2009) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 8. Woman Abuse Projects: Dissemination of stalking educational materials (2002);CME for family physicians (2005); HIV-PEP (2006); SADVTC protocols for drug facilitated sexual assault (2007); McMaster VAW Research Program (2008) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 4 5 more sig. 9. Demonstration Projects 20+ individual projects plus process learnings. 1 less sig. 2 3 - 18 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports 10. Osteoporosis Reports: A Framework and Strategy for the Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis, (2000); Development of a Model for Integrated Post-Fracture Care in Ontario (2003); Projects: Public awareness campaign (2003) CME on osteoporosis and falls prevention (2005) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 11. Chronic Conditions Report: Literature Review – Behavioural Guidelines for Adjusting to Medical Conditions (2001); Project: Burden of Illness and Disability (2007) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 12. Health Risk Behaviours Report: Literature Review on the Best Mechanisms to Influence Health Risk Behaviours (2000); Projects: Healthy Eating Roundtable (2001); Healthy Measures toolkit (2003); Translation of Canada’s Food Guide (2003); Healthy eating intervention evaluation (2003) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 13. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Report: Achieving Best Practices in the Use of Hysterectomy (2002); Project: CME on best practices for abnormal uterine bleeding (2007) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 14. Homelessness and Social Isolation Reports: Health Status of Homeless Women – An Inventory of Issues (2002); Models and Practices in Service Integration and Coordination for Women Who are Homeless or At-Risk of Homelessness: An Inventory of Initiatives (2003) 1 less sig. 2 3 - 19 - 4 5 more sig. Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports 15. Incontinence Projects: Survey (2004); “Improving Continence Care in Complex Continuing Care (IC5)” quality improvement model (2005) 1 less sig. 2 3 4 5 more sig. 16. Other _________________________________________________________________ 1 less sig. 2 3 - 20 - 4 5 more sig. Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Appendix 2: OWHC KT Project – User Focus Group Guide Preamble: • • • Welcome [Facilitator] Self-introduction by group members Introduce the Knowledge Capsules project [Project Assistant] Stage One – Orientation Objective: Orients group members to the subject matter under discussion. Identify unmet needs and unsolved problems associated with the topic under discussion. Questions 1. Do you use research results in your policy development work? Please describe how and when. Probe for specific examples, if appropriate. 2. What are the main benefits of using research results? Probe for additional benefits and/or specific examples of when the process of using research has been especially valuable. 3. What are the main challenges? Probe for additional challenges and/or specific examples of when the process of using research has been especially difficult. 4. What makes it easy for you to use research results? 5. What makes it hard? Stage Two – Exposure Objective: Determine initial reactions to the product concept • bullet-point descriptions printed on large flip chart or PowerPoint slides can be used to display our initial concepts; this should be structured around the content extraction framework. Preamble: Now we’d like to get your reaction to some of the ways we’ve been thinking about presenting brief summaries developed specifically for the types of policy development activities you might be involved with. These have been drafted based on what we know from the research literature on how policy-makers seek and use research evidence, and we’ve had input from experts in the field. That said, it won’t be a user-centred product until we hear from users – that’s you. So please be very honest – whether positive or negative – since your feedback will very much determine what the final products look like. 6. From the research reports commissioned by the OWHC, we can extract and summarize the following type of content. - 21 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Background: • How the project came about • What the problem is and why it’s important • Scope, context & purpose of the research in the Ontario and/or Canadian context • Definitions where necessary Methods: • Very brief description of the approach and sample (i.e., “this survey was conducted in March 2005 with 642 randomly sampled Ontario women.”) Key Findings • key findings stated at a very high level, avoiding use of statistics, except basic percentages, proportions, or odds (i.e., “women with depression were 4 times more likely to also indicate current exposure to partner violence” or “32% of women in group X had outcome A, compared to 12% of women in group Y”, or, “32% of women …, however the true effect can range anywhere from 27% to 37%”) Interpretation & Recommendations • What the study adds to what we know • Recommendations/implications of the new data for policy, practice, research, and education and gaps in knowledge that may require future research • cost implications (if available) • the researchers’ view of what the ideal situation would be and what is needed to make the problem better 7. After identifying and summarizing the contents of the report, a next step is to try to add value to what’s available in the report by incorporating the following elements • Summary of the assessment of the quality of the report – i.e., can these results be trusted? • New and relevant information available on the topic since completion of the report. • Recommendations framed in terms of the implications for the four areas identified: policy, practice, research, education: o either re-iterate those from the report if there’s congruence with new or external evidence, or o state different recommendations and be explicit about why they differ from those of the report (e.g., new evidence) • What other policy makers have decided around the topic in relevant jurisdictions. • Controversies related to the topic (brief summary citing key materials) • Who to contact for more information, and/or where to look for more information - 22 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports 8. How long do you think these should be? is there a minimum length? maximum? 9. What the best way to get these types of summaries to you? Probes re: push/pull; online or other; timing/frequency 10. Is there anything else you can think of at this point that would help us draft some samples for you to review online? Wrap-Up • reminder re: online space – we’ll send email notification when drafts are available for review, with links and instructions for accessing and providing feedback • reminder re: focus group in the new year – maybe try to book the date while people are in the room? target mid-late January • thanks and give project representative’s contact info in case they think of anything they want to add in the next couple of days - 23 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Appendix 3: OWHC KT Project – Sample Interview Guide Preamble: In a recent poll of current and former OWHC members, the topic of <topic> was identified as a priority for inclusion in the knowledge capsules project. It is felt that key messages arising from the work in this area might benefit those who work in areas related to women’s health (e.g. MOHLTC, the government of Ontario and the new Women’s Health Institute). The learnings from the <topic> project are process-oriented rather than content-specific research findings. For this reason, we are conducting in-depth interviews with those familiar with these projects in order to document the key “lessons learned” related to the process of developing and implementing this kind of initiative. Interview Guide: Please tell me about the OWHC <topic> initiative, and your role within it. Probes: when did it start? What were its stated goals and objectives? When did you become involved? What specific activities were undertaken in this initiative? What were the initiative’s main accomplishments? Probe (if more than one listed): can you rank these? What were the initiative’s main shortcomings (if any)? Probe (if more than one listed): can you rank these? To what do you attribute these shortcomings? (e.g., internal factors, such as resourcing; external factors such as the wider political climate, etc.) If you were going to do this over again, what aspects would you keep? Probe: why were these especially valuable? What would you do differently? Probe: why? What was the most surprising thing to you regarding this initiative? If you were giving advice to someone thinking about conducting an awareness-raising initiative for a women’s health topic, what would it be? Since the completion of the project, as you continue to work in your field, are there any other recommendations for people conducting this type of awareness-raising initiatives in the future? Would you do this again? Probe: why or why not? If not, what would be required to change your mind? - 24 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports Appendix 4: OWHC KT Project - Content Extraction Tool Purpose: This framework guides identification and extraction of key content from the identified priority areas for this project. Also included is a section on “value-added” information incorporated into the final information product to make it more relevant and accessible to decision-makers. Content is extracted from reports available for each topic and when unavailable, the gaps are flagged and a decision made regarding whether/ how to find and include this information. NOTES: 1) This framework was developed iteratively, with input from end users sought during planned focus groups and incorporated using an online revision process. 2) It has two parts: a) the first sections guide the extraction of specific content from the reports themselves; b) the separate “value-added” section at the end is for the information sought, created and integrated to formulate recommendations (or reiterate those of the report) and implications for policy (practice, research, education). This includes comments related to assessment of the methodological quality (and hence utility, generalizability, etc.) of the content. From the “Background” Section: • How the project came about – what were the factors that led to the study (when relevant, e.g. because of a controversy) • Define the problem, including why it’s important – 1-3 lines • Scope/ Context & Purpose of the available content within the Ontario and/or Canadian context • Definitions where necessary From the “Methods” Section: • Very briefly describe the approach and sample (i.e., “this survey was conducted in March 2005 with 642 randomly sampled Ontario women.”) Summary of Key Findings • This can vary significantly from report to report in terms of the type of findings available, and how they are reported. • In general, key findings should be stated at a very high level and avoid use of statistics, except basic percentages, proportions, or odds (i.e., “women with depression were 4 times more likely to also indicate current exposure to partner violence” or “32% of women in group X had outcome A, compared to 12% of women in group Y”). Where available, include 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and a sentence that interprets them (i.e., “32% of women …, however the true effect can range anywhere from 27% to 37%”) From the “Discussion” Section: • What the study adds to what we know about the issue for women’s health in Ontario (1-2 lines). • Describe any specific limitations to the methods or the generalizability of the findings as stated by the authors themselves (1-2 lines). - 25 - Handbook for Synthesizing Research Reports From the Report’s “Recommendations” • Extract all recommendations/implications of the new data for: 1. 2. 3. 4. policy practice research education • Extract all recommendations/implications for future research based on identification of existing gaps in knowledge. • Extract all information related to cost implications. • Extract all information related to the authors’ statement of what the ideal situation would be and what is needed to make the problem better Notes on this section: i. In the reports under review, there are at least two types of recommendations depending on the type of study. Some reports identify the problem while others provide recommendations. ii. This information is often included in the report’s executive summary, but is often quite vague. Therefore, more concrete examples from the full text might need to be sought. iii. There are different levels to the recommendations (i.e., broader health care system, program development, clinical level HCP enhanced practice) – it is important to be explicit about what the report is and is not recommending and for whom. iv. Not all reports provide explicit guidance for each of the 4 areas identified above, but this should be made clear – if there’s nothing re” “education” then there should be a heading with “no specific recommendations available” indicated. “Value-added” information: (to be generated by the summary team, and/or sought from external sources, including responding to what the end users indicate) • The summary team’s assessment of the methodological quality of the report [NOTE: how this will be done (what criteria), who will do it, and how it will be reported need to be decided a priori] • New and relevant information available on the topic since completion of the report. • The summary team’s recommendations framed in terms of the implications for the four areas identified: policy, practice, research, education: o either re-iterate those from the report if we agree and there’s congruence with new or external evidence, or o state different recommendations and be explicit about why they differ from those of the report (e.g., new evidence) • What other policy makers have decided around the topic in other relevant jurisdictions. • Controversies related to the topic (briefly summarize and cite any key materials) • Who to contact for more information, or where to look for more information - 26 -

© Copyright 2026