How To Spot CV Fraud

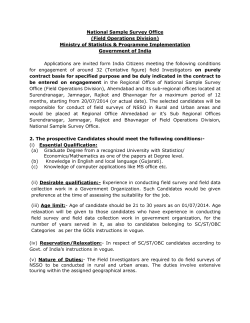

How To Spot CV Fraud (and when a candidate is lying on social media) HOW TO SPOT CV FRAUD (and when a candidate is lying on social media) We live in desperate times; a larger pool of candidates is chasing a small number of job opportunities and employers, faced with a bountiful supply of applicants, are only willing to hire the very best. The temptation for candidates to exaggerate their skills or experience has seldom been higher, while the risk for recruiters to fall victim to CV fraud is on the up. Figures provided by pre-employment screening firm HireRight, which primarily focuses on financial services, suggest that 36% of candidates securing roles in 2011 had “some sort of discrepancy” on their CV. Candidates bending the truth on their CVs is nothing new, but as in-house recruitment teams now have fewer opportunities to hire and third-party recruiters are operating in an ever-more competitive environment, the costs of taking on the wrong person are arguably higher. What should alert you to a rogue candidate and what are the risks of recruiting someone via social media? Where candidates are most likely to lie There have been some high profile or extreme cases of CV fraud recently. Most notably, Yahoo CEO Scott Thompson whose faked degree in computer science went unchecked until his latest position and Paul Gwinnell, who managed to secure a role as deputy chief executive of Middle Eastern bank, Ahli United Bank, before it was discovered he’d falsified degrees from Oxford and Harvard as well as lying about working for J.P. Morgan for 20 years. Most candidates are more subtle in the ways they look to dupe employers, however. Ironically, considering the large number of redundancies in the financial sector over the past five years and the potential for unexplained employment gaps, candidates are more likely to lie about their education. According to HireRight, 25% of candidates looked to falsify their grade, qualification type or the date of the award in 2011, up from 19% in 2010. “When providing educational information, candidates can say that they attended a particular university, when they were never actually awarded a degree, or upgrade a high 2:2 award into a 2:1,” says Dan Shoemaker, senior managing director at HireRight. “Or often they can change the university name to put a better brand on their CV – Oxford Brooks to Oxford University, for example.” “Falsifying degrees happens within the senior ranks more than you would think, with some candidates putting it on their CV for so long they assume no one would check,” adds Tim Rooney, commercial director at Experian Consumer Information Services. “However, we also see a lot of GSCE and A-Level grades exaggerated or faked because again it’s assumed that this isn’t something employers check up on. Generally, it’s more common for junior candidates to lie about academic qualifications, however.” Don’t be blinded by jargon When it comes to employment history, many candidates think they can impress (or confuse) recruitment professionals with technical terminology, with the assumption that their knowledge of financial markets or a particular job role is perfunctory enough for discrepancies to slip through unchecked. “Candidates may try to use jargon to baffle a recruiter, assuming that they won’t understand the technical details of their role,” says Sarah Kennedy, manager at Hays Financial Markets. “This is not the case; we will drill down into the details of their professional assessments to make sure everything is as it should be.” Some sectors are easier to verify than others, however. For example, it’s difficult for a trader to lie about their performance, as this is something that can easily be checked. However, if relationship manager overstates their connection to a client, or a technologist claims that they have a deeper understanding of a particular programming language than is really the case, this is hard to dispute without further testing. In investment banking, it’s common for applicants to exaggerate their involvement in particular deals. Something that looks too good to be true on a CV very often is. “One example is when we’ve encountered someone working in M&A with a very impressive deal list, who claimed to have been instrumental in the transactions, but on further investigation it turned out they only had a very administrative role,” says Shoemaker. “This is something that’s not easy to check, particularly at the more junior end.” Mind the gaps Gaps on CVs shouldn’t necessarily be viewed as a negative. After all, the Centre for Economics and Business Research suggests that 99,000 roles have been eliminated from the City of London since 2007 and getting back into job market in the current climate is no easy task. However, any gaps still need to be treated with scepticism. “If someone has a number of short-term jobs on their CV it should be investigated,” says Rooney. “In the current climate people are falling victim to redundancy or could have left voluntarily if the role wasn’t right for them, but it’s still possible that the gap was because they were fired for incompetence or were under criminal investigation.” It’s now increasingly important for any recruiter to check the exact day and months of prior employment at a particular company. Thoroughly quiz candidates at an early stage and don’t just rely on the references provided. Call their previous employer to double check any concerns you may have, suggests Shoemaker. Should checks be carried out earlier on? Assuming no red flags have been raised on the CV, a candidate has sailed through the interview process, made it through the final shortlist and then been handed the offer, this is the point that most verification checks are made. Is this too late? After all, as well as the cost of advertising and promotion, there’s also the use of HR staff and recruiters’ time – across all industries, on average employers pay £5.3k for each new hire, according to research firm Bersin & Associates. “Typically, the most thorough checks, those that uncover undisclosed detrimental information, are made at the point of offer,” says Rooney. “At this point, I would argue it’s too late and the company has made a commitment of both time and money. I would like to see the industry perform these checks at the shortlisting phase, for the final five candidates for instance. “ What to bear in mind when using social media for recruitment It’s an undeniable fact of life that the use social media for recruitment is increasing. LinkedIn, Facebook and, to a lesser extent, Twitter can provide a lot of information about a potential recruit. On the one hand it’s a handy pre-screening tool – if someone claims to be a director of a particular investment bank, for instance, and has no connections to colleagues from that organisation on LinkedIn, alarm bells will inevitably be raised. However, there are a few things to bear in mind. “There are a lot of risks when recruiting through social media,” says Shoemaker. “On the one hand you see a lot of personal information that could put the recruiter in a tough position on discrimination – theoretically, you could find out their race, disability, sexuality or even political leanings, all of which could unfairly influence the recruitment process. “On the other, it’s impossible to verify the information on a social media profile. People can put as little or as much data about themselves as they like, they could link themselves to a particular employer without checks and position themselves as a more attractive candidate than is actually the case. It’s a grey area as a screening tool,” he says. More recently, there’s been a storm of controversy around employers asking for potential recruits’ Facebook passwords in an attempt to vet applicants. Aside from issues about the legality of the practice, it’s questionable how much value any employer would gain from this. HireRight tells us that it reviewed the Facebook pages of 5,000 applicants (without having access to their passwords). More than half of people displayed no public information on their Facebook page and, of those that did allow access, the majority had ‘neutral information’. Less than 1% had some sort of information that would be deemed ‘actionable’, says Shoemaker.

© Copyright 2026