What Is the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Dental Student Clinical Performance?

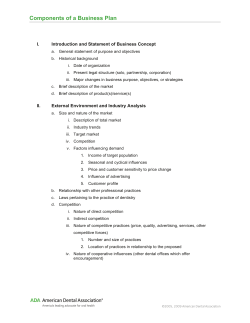

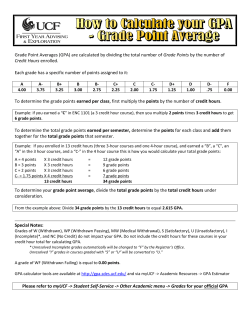

What Is the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Dental Student Clinical Performance? Kristin Zakariasen Victoroff, D.D.S., Ph.D.; Richard E. Boyatzis, Ph.D. Abstract: Emotional intelligence has emerged as a key factor in differentiating average from outstanding performers in managerial and leadership positions across multiple business settings, but relatively few studies have examined the role of emotional intelligence in the health care professions. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and dental student clinical performance. All third- and fourth-year students at a single U.S. dental school were invited to participate. Participation rate was 74 percent (100/136). Dental students’ EI was assessed using the Emotional Competence Inventory-University version (ECI-U), a seventy-two-item, 360-degree questionnaire completed by both self and other raters. The ECI-U measured twenty-two EI competencies grouped into four clusters (Self-Awareness, Self-Management, Social Awareness, and Relationship Management). Clinical performance was assessed using the mean grade assigned by clinical preceptors. This grade represents an overall assessment of a student’s clinical performance including diagnostic and treatment planning skills, time utilization, preparation and organization, fundamental knowledge, technical skills, self-evaluation, professionalism, and patient management. Additional variables were didactic grade point average (GPA) in Years 1 and 2, preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2, Dental Admission Test academic average and Perceptual Ability Test scores, year of study, age, and gender. Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted. The Self-Management cluster of competencies (b=0.448, p<0.05) and preclinical GPA (b=0.317, p<0.01) were significantly correlated with mean clinical grade. The Self-Management competencies were emotional self-control, achievement orientation, initiative, trustworthiness, conscientiousness, adaptability, and optimism. In this sample, dental students’ EI competencies related to Self-Management were significant predictors of mean clinical grade assigned by preceptors. Emotional intelligence may be an important predictor of clinical performance, which has important implications for students’ development during dental school. Dr. Victoroff is Associate Dean for Education and Association Professor of Community Dentistry, School of Dental Medicine, Case Western Reserve University; Dr. Boyatzis is Distinguished University Professor and Professor in the Departments of Organizational Behavior, Psychology, and Cognitive Science, Case Western Reserve University. Direct correspondence and requests for reprints to Dr. Kristin Zakariasen Victoroff, School of Dental Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44106-4905; 216-368-6616 phone; 216-368-3204 fax; [email protected]. Keywords: dental education, dental students, clinical education, emotional intelligence Submitted for publication 12/29/11; accepted 6/17/12 T he work professionals do is of great importance to society because it impacts the health, security, and well-being of those served.1,2 Educators in the professions are faced with the challenge of selecting individuals for admission to professional education programs who are most likely to perform in a superior manner. Cognitive ability has traditionally been the primary measure upon which such decisions are based. Although educators agree that cognitive ability is necessary in professional work, they have expressed concern that it is not a sufficient condition to guarantee professional excellence. Emmerling and Goleman have noted that “traditional measures of intelligence, although providing some degree of predictive validity, have not been able to account for a large portion of the variance in work performance.”3 Research in the area of emotional intelligence has provided important insights regarding what else 416 is required for superior professional performance. Emotional intelligence, as defined by Goleman, refers to “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions well in ourselves and in our relationships. It describes abilities distinct from, but complementary to, academic intelligence, the purely cognitive capacities measured by IQ.”4 Emotional intelligence forms the basis for an individual to develop and use emotional intelligence competencies.5 These competencies enable an individual to, for example, accurately read and respond to the moods of others, remain calm in stressful situations, remain optimistic in the face of setbacks, adapt to changing circumstances, seek out opportunities, and work effectively in groups.4 Emotional intelligence has been linked to performance in a variety of managerial and executive positions across multiple business settings and has Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 77, Number 4 emerged as a key factor in differentiating average from outstanding performers.6 Although there is a great deal of evidence linking emotional intelligence to superior performance in managerial and leadership roles, there have been fewer studies to date examining emotional intelligence in the health care professions. Many behaviors that characterize exemplary professional practice in health care may reflect underlying abilities related to emotional intelligence. For example, exemplary professionals are expected to put patient needs ahead of their own interests, strive to perform to a high standard at all times, continually self-assess their knowledge and skills, know their limitations, and act with integrity.1 Educators and researchers in medicine, dentistry, and nursing have expressed interest in emotional intelligence as a potentially important factor in student selection and in student, resident, and practitioner training, as well as a predictor of clinician performance and patient outcomes.7-22 There is a need for additional empirical studies. In dental education, the literature reveals long-standing interest in predictors of dental student performance. Traditional cognitive measures, such as undergraduate grade point average (GPA) and standardized Dental Admission Test (DAT) scores, are useful in predicting performance in the didactic components of the curriculum. However, these measures have been less helpful in predicting how a student will perform in the clinical setting.23-26 There is, therefore, significant interest in identifying noncognitive factors that may be associated with clinical performance. There are good reasons to investigate emotional intelligence as a possible noncognitive predictor of dental student clinical performance. In a significant portion of the curriculum, students spend their time providing patient care in the clinical setting. Many of the skills and abilities now considered important for clinical effectiveness appear to be related to the emotional intelligence competencies articulated by Goleman4 and Goleman et al.6 These include communication skills, patient management skills, ability to work with a multicultural patient population, and ability to collaborate with others and lead teams.27 In the clinical environment, students must engage in complex management of both themselves and others (patients, clinical instructors, support staff, and peers) as they apply the knowledge and skills gained during the didactic and preclinical portion of the curriculum. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between emotional April 2013 ■ Journal of Dental Education intelligence and dental student clinical performance. The two main hypotheses tested were the following: 1) there is a relationship between students’ cognitive ability and didactic academic performance, and 2) there is a relationship between students’ emotional intelligence and clinical performance. Models of Emotional Intelligence The prevailing models of emotional intelligence have been articulated by Goleman,4 Goleman et al.,6 Boyatzis,28 Mayer et al.,29 and Bar-On.30 Although the models differ in the specific ways in which emotional intelligence is conceptualized, all focus on the recognition and management of emotions in self and others.3 There is agreement among these theorists that emotional intelligence is distinct from traditional intelligence (IQ). The Goleman and Boyatzis model has its roots in the work of Boyatzis, who developed a theory of managerial competencies that differentiate average from superior performers.31 Emmerling and Goleman noted that “though not originally a theory of social and emotional competence, as research on ‘star’ performers began to accumulate, it became apparent that the vast majority of competencies that distinguish average performers from ‘star performers’ could be classified as falling into the domain of social and emotional competencies.”3 The Goleman and Boyatzis model is unique among the prevailing theories of emotional intelligence in its focus on developing a “theory of work performance based on . . . emotional competencies.”3,28 In this model, emotional intelligence is defined as “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions effectively in ourselves and others,” and an emotional competence is “a learned capacity based on emotional intelligence that contributes to effective performance at work.”32 The Goleman and Boyatzis model consists of emotional competencies grouped into four clusters.6 The model continues to be refined (the current model can be found at www.eiconsortium.org). The twentytwo competencies included in the model at the time of this study, grouped into four clusters, are shown in Table 1. The instrument associated with the Goleman and Boyatzis model is the Emotional Competence Inventory-University version (ECI-U). The ECI-U is a seventy-two-item, 360-degree assessment ques- 417 Table 1. Goleman and Boyatzis model of emotional intelligence: clusters and competencies Self-Awareness Knowing one’s internal states, preferences, resources, and intuitions Emotional Awareness: Recognizing one’s emotions and their effects. Accurate Self-Assessment: Knowing one’s strengths and limits. Self-Confidence: A strong sense of one’s self-worth and capabilities. Self-Management Managing one’s internal states, impulses, and resources Emotional Self-Control: Keeping disruptive emotions and impulses in check. Adaptability: Flexibility in handling change. Achievement: Striving to improve or meeting a standard of excellence. Initiative: Readiness to act on opportunities. Optimism: Persistence in pursuing goals despite obstacles and setbacks. Trustworthiness: Maintaining integrity. Conscientiousness: Taking responsibility for personal performance. Social Awareness How people handle relationships and awareness of others’ feelings, needs, and concerns Empathy: Sensing others’ feelings and perspectives, and taking an active interest in their concerns. Organizational Awareness: Reading a group’s emotional currents and power relationships. Service Orientation: Anticipating, recognizing, and meeting customers’ needs. Cultural Awareness: Respecting and relating well to people from varied backgrounds. Relationship Management Skill or adeptness at inducing desirable responses in others Developing Others: Sensing others’ development needs and bolstering their abilities. Inspirational Leadership: Inspiring and guiding individuals and groups. Change Catalyst: Initiating or managing change. Influence: Wielding effective tactics for persuasion. Conflict Management: Negotiating and resolving disagreements. Communication: Listening openly and sending convincing messages. Building Bonds: Nurturing instrumental relationships. Teamwork and Collaboration: Working with others toward shared goals and creating group synergy in pursuing collective goals. Source: Sala F. Emotional competence inventory (ECI) technical manual. Boston: Hay Group, 2002. At: www.eiconsortium.org/measures/eci_360.htm. Accessed: June 26, 2006. tionnaire completed by both self and other raters.32 This instrument has been used extensively for both developmental and research purposes in work and academic settings. The ECI-U was selected for use in this study because of its focus on the work setting, which is consistent with the study’s focus on dental students’ performance in the professional setting. In addition, the ECI-U utilizes a 360-degree assessment based on observations of the individual’s behavior by others, instead of relying solely on self-reported data. Methods All Year 3 (sixty-nine) and Year 4 (sixty-seven) students enrolled in the four-year D.M.D. program 418 at the School of Dental Medicine at Case Western Reserve University were invited to participate in the study. All third- and fourth-year students were actively engaged in the clinical aspect of the curriculum, spending an average of thirty hours per week in the clinical setting. Each student received a letter of invitation to participate. In addition, the investigator described the study in person during a class session. Participation was voluntary, and the study protocol was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Each student participant signed a consent form and completed an ECI-U Self-Assessment Questionnaire. Individuals identified as other raters (patient care coordinators, clinical preceptors, and peers) also received a letter describing the study and inviting their participation, a consent form, and Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 77, Number 4 an ECI-U Other Assessment Questionnaire for each student they were asked to assess. Year of study, age, gender, DAT academic average and Perceptual Ability Test (PAT) scores, didactic GPA, preclinical GPA, and clinical grades assigned by clinical preceptors are on file with the dental school registrar and were released for those students who had agreed to participate in the study. Data were analyzed using SPSS 14.0. The study constructs were cognitive ability, perceptual ability, didactic performance, preclinical performance, clinical performance, and emotional intelligence. The corresponding study variables were DAT academic average and PAT scores, didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2, preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2, clinical grades assigned by clinical preceptors, and ECI-U ratings. Cognitive ability, the first construct, was measured using the DAT academic average score, which is the arithmetic mean of the biology, general chemistry, organic chemistry, quantitative reasoning, and reading comprehension subtest scores.33 This score is accepted as a measure of general cognitive ability. Smithers et al. noted that, “In particular, the DAT academic average is a measure of general cognitive ability. . . . Individuals with high cognitive ability should have more success in academic components of their programs.”26 Perceptual ability, the second construct, was measured using the DAT PAT score. Didactic performance, the third construct, was measured using the weighted GPA from all didactic courses in Years 1 and 2. Preclinical performance, the fourth construct, was measured using the weighted GPA from all preclinical laboratory courses in Years 1 and 2. Clinical performance, the fifth construct, was measured using clinical grades assigned by clinical preceptors. Students are assigned two types of grades in the clinical component of the curriculum. One set of grades is derived from individual clinical competency examinations designed to determine a student’s proficiency in performing specific clinical procedures. These grades are almost exclusively a measure of technical skill, so an association between emotional intelligence and these grades was not predicted. These grades were not included in the analyses. The second set of grades is assigned by clinical preceptors based on their overall rating of a student’s clinical performance. In assigning these grades, the preceptors take a more holistic view of the student’s performance based on multiple April 2013 ■ Journal of Dental Education observations over many weeks. Assessment criteria focus on such aspects of clinical performance as diagnosis and treatment planning skills, work ethic and time utilization, preparation and organization, fundamental knowledge, technical skills, self-evaluation, professionalism, and patient management. An association between these grades and emotional intelligence was predicted. These grades are the dependent variable in this study. In the clinical setting, each student works closely with two clinical preceptors who supervise the student’s patient care activities and a patient care coordinator who is responsible for patient scheduling. Students are assigned two grades (one from each clinical preceptor) in December and May of the third and fourth years. The average of the preceptor grades was used. Emotional intelligence (EI), the final construct, was measured with the ECI-U, which is designed to assess “how a person expresses handling of emotions in life and work settings.”32,34 In addition to the twenty-two EI competencies, the instrument measures two cognitive competencies, with three items per competency. Each item describes a specific behavior, and the rater is asked to indicate how often the individual demonstrates, shows, or uses the behavior. Possible ratings range from 1 (never shown) to 5 (consistently shown). If a rater has not had the opportunity to observe a behavior, it is recorded as “n” (have not had the opportunity or don’t know). The two cognitive competencies were not included in the analyses for this study. Administration of the ECI-U results in two sets of ratings: self-ratings and others’ ratings. In the ECI-U technical manual, Sala notes that ECI selfratings may be used for developmental purposes, but “they do not provide valid and reliable measures of emotional intelligence for research purposes.”32 The analyses conducted for our study included only the ratings of others: patient care coordinators, clinical preceptors, and dental student peers. The mean other ratings for each of the twenty-two competencies and each of the four clusters were calculated as specified in the ECI-U technical manual. The four “other rater” cluster ratings (Self-Awareness, Self-Management, Social Awareness, and Relationship Management clusters) were included in the study analyses. Since the sample consisted of two cohorts of students (one in the third year and one in the fourth year), year of study was included in the analyses as a control variable. Age and gender were also included in the analyses as control variables. 419 *p<0.05, **p<0.01, two-tailed test Note: Spearman’s rho was calculated for correlations between year of study or gender and other study variables. Pearson’s r was calculated for correlations between all other study variables. Year of study is dummy coded as Year 3=0 and Year 4=1. Gender is dummy coded as female=0 and male=1. 0.058-0.041 -0.246* -0.112-0.019 0.1110.183 0.380** 0.427**0.434** 1.00 0.1070.061-0.043 -0.0800.0260.0050.261** 0.377** 0.416** 0.436** 0.839** 1.00 0.045-0.011 -0.090-0.130-0.033 0.0330.189 0.255*0.146 0.289** 0.763**0.831** 1.00 0.062 -0.141 -0.129 -0.120 -0.028 0.200* 0.216* 0.329** 0.329** 0.370** 0.827** 0.770** 0.800**1.00 0.44 0.41 0.44 0.51 3.96 3.95 4.05 3.77 — — 1.00 — — -0.013 1.00 27.67 3.00 0.205* 0.305** 1.00 18.48 1.70 -0.076 0.136 0.092 1.00 18.62 1.81 0.051 0.235* 0.014 0.266** 1.00 3.21 0.42 -0.037 -0.057 0.024 0.419** 0.119 1.00 3.41 0.33 -0.0710.153 0.056 -0.0510.364** 0.276** 1.00 3.25 0.48 -0.068 -0.055 -0.198* 0.005 -0.046 0.192 0.292** 1.00 3.74 0.33 — 0.000 -0.190 0.102 0.033 0.138 0.409* 0.618** 1.00 3.36 0.43 0.210* -0.042 -0.178 -0.059 -0.027 0.142 0.271** 0.921** 0.840** 1.00 Year of study Gender Age (years) DAT academic average PAT Didactic GPA Preclinical GPA Clinical GPA Year 3 Clinical GPA Year 4 Clinical GPA Years 3 and 4 EI Self-Awareness EI Self-Management EI Social Awareness EI Relationship Management Year DAT Clin Clin of Acad Didactic Preclin GPA GPA Clin EIEIEI EI Mean SD Study Gender Age Average PAT GPA GPA Year 3 Year 4 GPA SA SM SocA RM Table 2. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations (N=100) 420 Results The participation rate was 74 percent (100/136). Of the participating students, 62 percent (62/100) were third-year students, and 38 percent (38/100) were fourth-year students. These numbers reflect a participation rate of 90 percent (62/69) for third-year students and 57 percent (38/67) for fourth-year students. Data collection began in March, and the variation in rate of participation can be attributed primarily to senior students’ proximity to graduation in the month of May. As graduation approached, seniors focused on completing mandatory tasks and were less inclined to complete optional tasks, such as participation in the study. Participating students were 77 percent (N=77) male and 23 percent (N=23) female. The gender distribution of the student body at the time of the study was 73 percent male and 27 percent female. Mean age of participating students was 27.7±3.0 years, with a minimum of 22.5 years and a maximum of 38.5 years. A total of 453 ECI-U Other Assessment questionnaires were completed by other raters (clinical preceptors, peers, and patient care coordinators). Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the study variables are shown in Table 2. Bivariate correlations were calculated using Pearson’s r, with the exception of correlations involving year of study or gender, for which Spearman’s rho was calculated. Clinical grades in Year 3 and Year 4 were highly correlated (r=0.618, p<0.01). Therefore, for fourth-year students the average of Year 3 and Year 4 clinical grades was calculated and used in all subsequent analyses. For third-year students, average Year 3 clinical grade was used in all subsequent analyses. Year of study was entered as a control variable in all subsequent analyses. A t-test was performed to determine if the two cohorts of students differed in their clinical performance in Year 3. There was no significant difference between mean Year 3 grade of third-year students (M=3.29, SD=0.43) and mean Year 3 grade of fourth-year students (M=3.20, SD=0.55, t[98]=0.942, p=0.348). Multivariate Analyses Didactic performance. Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the contri- Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 77, Number 4 bution of the DAT scores (academic average and PAT) and the four ECI-U cluster ratings (Self-Awareness, Self-Management, Social Awareness, and Relationship Management) in predicting didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2. Control variables were year of study, age, and gender. In all multiple linear regression analyses, year was dummy coded as Year 3=0 and Year 4=1. Gender was dummy coded as female=0 and male=1. The results of these analyses are shown in Table 3. Model 1 is the regression of didactic grades in Years 1 and 2 on year of study, gender, age, DAT academic average score, and PAT score. DAT academic average score was positively correlated with didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2 (ß=0.424, p≤0.001). Model 2 is the regression of didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2 on year of study, gender, age, DAT academic average score, PAT score, and the four ECI-U cluster ratings. DAT academic average score (ß=0.442, p≤0.001) and the Relationship Management cluster rating (ß=0.507, p≤0.01) were positively correlated with didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2. The Self-Management cluster rating was negatively correlated with didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2 (ß=-0.398, p≤0.05). Preclinical performance. Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the contribution of the DAT scores (academic average and PAT), didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2, and the four ECI-U cluster ratings in predicting preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2. Control variables were year of study, age, and gender. The results of the analyses are shown in Table 4. Model 1 is the regression of preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2 on year of study, gender, age, Table 3. Regression of didactic GPA on DAT scores, ECI-U cluster scores, and control variables (N=100) Independent Variable Standardized Regression Coefficients Model 1 Model 2 Year of study -0.009 -0.011 Gender -0.138-0.070 Age 0.017 0.083 DAT academic average 0.424*** 0.442*** PAT 0.038 0.041 EI Self-Awareness 0.186 EI Self-Management -0.398* EI Social Awareness -0.123 EI Relationship Management 0.507** R2 Change in R2 0.193 — 0.314 0.121** *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 Table 4. Regression of preclinical GPA on DAT scores, didactic GPA, ECI-U cluster scores, and control variables (N=100) Independent Variable Standardized Regression Coefficients Model 1 Model 2 Year of study -0.077 -0.074 Gender 0.114 0.167 Age 0.054 0.048 DAT academic average -0.180 -0.342*** PAT 0.388*** 0.373*** Didactic GPA 0.383*** EI Self-Awareness EI Self-Management EI Social Awareness EI Relationship Management R2 Change in R2 0.179 — 0.297 0.118*** Model 3 -0.089 0.139 0.019 -0.336*** 0.360*** 0.402*** -0.204 0.430* -0.045 0.002 0.357 0.061 *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 April 2013 ■ Journal of Dental Education 421 DAT academic average score, and PAT score. PAT score was positively correlated with preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2 (ß=0.388, p≤0.001). Model 2 is the regression of preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2 on year of study, gender, age, DAT academic average score, PAT score, and didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2. DAT academic average score was negatively correlated with preclinical GPA (ß=-0.342, p≤0.001). PAT score was positively correlated with preclinical GPA (ß=0.373, p≤0.001). Didactic GPA was positively correlated with preclinical GPA (ß=0.383, p≤0.001). Model 3 is the regression of preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2 on year of study, gender, age, DAT academic average score, PAT score, didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2, and the four ECI-U cluster ratings. DAT academic average score was negatively correlated with preclinical GPA (ß=-0.336, p≤0.001). PAT score (ß=0.360, p≤0.001), didactic GPA (ß=0.402, p≤0.001), and Self-Management cluster rating (ß=0.430, p≤0.05) were positively correlated with preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2. Clinical performance. Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the contribution of the DAT academic average score, PAT score, didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2, preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2, and the four ECI-U cluster ratings in predicting clinical grade. Control variables were year of study, age, and gender. The results of the analyses are shown in Table 5. Model 1 is the regression of clinical grade on DAT academic average score, PAT score, and the control variables. Year of study (ß=0.236, p≤0.05) was positively correlated with clinical grade. Age (ß=-0.212, p≤0.05) was negatively correlated with clinical grade. Model 2 is the regression of clinical grade on DAT academic average score, PAT score, didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2, preclinical GPA in Years 1 and 2, and the control variables. Year of study (ß=0.264, p≤0.01) and preclinical GPA (ß=0.341, p≤0.01) were positively correlated with clinical grade. Age (ß=-0.232, p≤0.05) was negatively correlated with clinical grade. Model 3 is the regression of clinical grade on DAT academic average score, PAT score, didactic GPA, preclinical GPA, the four ECI-U cluster ratings, and the control variables. Year of study (ß=0.221, p≤0.01), preclinical GPA (ß=0.229, p≤0.05), and Self-Management cluster rating (ß=0.490, p≤0.05) were positively correlated with clinical grade. Discussion This study explored the relationship between emotional intelligence and dental students’ clinical performance by examining the empirical association between students’ ECI-U cluster ratings and clinical grades. The results provide empirical support for a relationship between cognitive ability and didactic performance and between emotional intelligence and clinical performance. An empirical association between DAT academic average score and didactic GPA in Years 1 and 2 was found, providing support for the hypothesized relationship between cognitive ability and academic Table 5. Regression of clinical GPA (Years 3 and 4) on DAT scores, didactic GPA, preclinical GPA, ECI-U cluster scores, and control variables (N=100) Independent Variable Standardized Regression Coefficients Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Year of study 0.236* 0.264** 0.221** Gender 0.001 -0.028 -0.058 Age -0.212* -0.232*-0.184 DAT academic average -0.012 0.018 0.012 PAT -0.028 -0.163-0.134 Didactic GPA 0.074 0.087 Preclinical GPA 0.341** 0.229* EI Self-Awareness 0.133 EI Self-Management 0.490* EI Social Awareness -0.313 EI Relationship Management 0.027 R2 Change in R2 *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01 422 0.088 — 0.203 0.116** 0.349 0.146** Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 77, Number 4 performance in the first two years of dental school. Neither DAT academic average score nor didactic GPA was correlated with clinical grade. These findings are consistent with prior research.24-26,33 An empirical association between ECI-U SelfManagement cluster rating and clinical grade was found, providing support for the hypothesized relationship between emotional intelligence and clinical performance. Students who were rated higher by others on the Self-Management cluster of competencies (which includes emotional self-control, achievement orientation, initiative, trustworthiness, conscientiousness, adaptability, and optimism) were more likely to perform well in the clinical setting. There was not a significant correlation between the Relationship Management cluster rating and clinical grade. In the clinical and preclinical settings, students primarily work on their own tasks (e.g., seeing their own patients, completing their own laboratory projects), rather than working on a group task. It seems reasonable to conclude that management of self (Self-Management cluster) would be more important than management of relationships with others (Relationship Management) in this particular context. Associations between Self-Awareness cluster rating and Social Awareness cluster rating and clinical grade were not found. Although the correlation between Social Awareness cluster rating and clinical grade was not statistically significant, it approached significance and therefore merits discussion. The near-significant negative correlation between Social Awareness cluster and clinical grade was unexpected but not inexplicable. The nature of the providerpatient relationship in the educational setting is unique, and this may influence the extent to which the competencies in the Social Awareness cluster are demonstrated. Christakis and Feudtner discuss the transient nature of the social relationships experienced by medical students and residents in training and the problems this creates.35 Student relationships with patients are generally of short duration in the educational setting, and, given multiple demands on the student’s time, the goal becomes the provision of treatment in the most efficient manner possible. This typically means that a patient’s immediate health problems are addressed (task orientation), but students do not spend a significant amount of time “getting to know” the patient (process orientation). Christakis and Feudtner observed that these transient interactions cause “patients and physicians to feel emotionally disconnected, and lead to care that too often is coldly competent.”35 April 2013 ■ Journal of Dental Education Sherman and Cramer examined empathy in dental students across the four years of training.36 First-year students’ scores on the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Health Professionals version (JSPE-HP) were significantly higher than scores of second-, third-, or fourth-year students. These authors concluded that “the timing in decline in empathy levels corresponded to increasing patient exposure.” In the educational setting, patient care goals may conflict with educational goals. Patients’ emotional needs are seen as an impediment to getting the “real work”—the exam or procedure—done. Pressures unique to the educational setting may push for behaviors that crowd out demonstration of Social Awareness competencies, although these competencies may prove to be valuable to students in their clinical practices after graduation. Two interesting correlations were found with respect to the association between ECI-U clusters and didactic GPA. The Relationship Management cluster was a predictor of didactic GPA, and the Self-Management cluster was negatively correlated with didactic GPA. Three conditions may explain the empirical association between the Relationship Management cluster and didactic GPA. First, the relationship management cluster is associated with an individual’s ability to influence others.6 It may be that those with stronger relationship management competencies were able to influence instructors in some way, perhaps by having their questions answered more frequently or by negotiating course logistics such as the timing of examinations. Second, in the dental school there is a tradition of more senior students’ helping junior students to succeed in didactic courses, by, for example, passing along lecture notes and offering advice about instructor expectations and how to study for a particular examination. There is no formal, standardized mechanism for the senior students to pass this information on to more junior students, so it can be expected that those who establish broader social networks among fellow students are likely to have greater access to such informal curricular resources. Finally, in a qualitative study of characteristics of effective learning experiences in dental school, studying in groups and learning from peers were found to be characteristics of effective learning experiences for some students.37 Again, those who display higher levels of more of the competencies in the Relationship Management cluster may be more likely to successfully form and sustain such study groups and will benefit from learning from their peers, perhaps leading to better didactic performance. 423 It is unclear why Self-Management cluster ratings were negatively correlated with didactic GPA. It may be that the nature of the task in the didactic setting differs significantly from the nature of the task in preclinical and clinical settings. In the didactic setting, in which basic sciences are taught, there is no end point in terms of the amount of material to be learned, and the amount of time in which it must be learned is limited. Therefore, a strategy adopted by many students for dealing with the massive amounts of information and limited time is to learn a topic “well enough” and then move on to the next topic, instead of aiming for perfect mastery of every topic. Displaying too much achievement orientation or conscientiousness may, in fact, work against students by leading them to try to master everything and become overwhelmed. In the preclinical setting, on the other hand, the goal is mastery of a well-defined set of tasks. Those with competencies such as achievement orientation, conscientiousness, and emotional self-control are likely to persist in trying to complete the task to a level of excellence, whereas others may hand in a product that is merely adequate. Limitations of the study must be considered. First, the validity and reliability of the outcome measure—clinical grades assigned by clinical preceptors—are somewhat unclear. Ranney et al. noted that the “generally unknown reliability of dental school grades included in studies” is a problem common to nearly all studies examining predictors of performance in dental school.23 Inclusion of grades assigned by more than one grader (the average of grades from two clinical preceptors was used in this study) helped to address this problem. In addition, the grading practices of the clinical preceptors were closely monitored by the assistant dean for clinical education, who intervened with and provided guidance to preceptors whose grade assignments seemed to be outliers. Although not a formalized calibration process, it is likely that this process provided some degree of calibration between preceptors. When Epstein and Hundert conducted an evidence-based review of current methods of assessing competence of medical students and residents, they found subjective ratings by supervising physicians was one of the three most frequently used assessment methods and the major form of assessment in the clinical setting.38 These authors discussed the limitations of this assessment method, including possible halo effect, sex/racial bias, and interrater variability. However, they also noted that more controlled outcome measures, such as ratings of student performance 424 made by standardized (i.e., simulated) patients used in a study of EI and clinical skills by Stratton et al.,9 did not provide information about students’ performance in real clinical settings with real patients. Epstein and Hundert concluded that subjective evaluations by clinical instructors “often (include) the tacit elements of professional competence otherwise overlooked by objective assessment instruments.” For the purposes of examining the relationship between EI and students’ overall clinical performance (not just discrete tests of specific skills but how students put all of their skills into practice in real clinical settings), clinical grades assigned by instructors were the best outcome measure available for use in our study. A second limitation of the study is that the sample of dental students was limited to students enrolled in one institution and one curriculum. The extent to which these findings can be generalized to dental students in other schools is not clear. Despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to the dental literature in that it examines the relationship between emotional intelligence and dental student clinical performance. It establishes the importance of noncognitive factors in students’ clinical performance, providing support for the role of emotional intelligence in clinical performance. However, additional studies are needed. For example, future studies could benefit from the inclusion of additional outcome variables, such as patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction data were collected for our study but ultimately were not included in the final analyses due to restriction in the range of responses. In the data collected, nearly all patients were completely or nearly completely satisfied, with a median satisfaction score of 24 on a 25-point scale and a mean score of 23.3±2.7. Seventy-five percent of responses indicated that the patient was completely satisfied (5 on a scale of 1 to 5), and 93 percent of responses were a 4 or 5. Restriction of range has been a problem in other studies that use patient satisfaction as an outcome measure.39,40 It will be an important challenge for future researchers to develop patient satisfaction measures that yield a range of patient responses and target specific aspects of satisfaction that may be expected to be related to provider emotional intelligence. This study focused on dental students, but future studies should also focus on dentists in clinical practice. In their literature review focusing on evaluation of applicants for admission to dental school, Ranney et al. noted that “we could not find Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 77, Number 4 studies that attempted to relate admissions criteria to success in practice, however that may be defined, or to serving populations of particular need, leadership positions, academic positions, or other needed service to society.”23 Such studies could include a variety of outcome variables, including, for example, new patient flow and patient retention, patient satisfaction, efficiency and financial viability of the practice, dentist career satisfaction, productivity and job satisfaction of the dental team members, and, ultimately, patient health outcomes. Given the relatively greater complexity of the clinical practice environment in comparison to the dental school clinical environment, we hypothesize that several of the EI clusters will be associated with superior performance in clinical practice. This hypothesis, however, remains to be tested. Do these findings minimize the role of cognitive ability and acquisition of knowledge in graduate and professional education? No. Several authors have concluded that cognitive ability and knowledge are threshold aspects of professional work, necessary but not sufficient for outstanding professional performance.3 Given that students are selected for admission based largely on evidence of cognitive ability (undergraduate GPA, DAT scores) and that admission is highly competitive, the student body is relatively homogeneous with respect to cognitive abilities. All are capable of gaining the requisite knowledge, and indeed all of the students who participated in our study passed all of their courses and advanced to the next year and/or graduated. One can conclude that all these students had the threshold amount of knowledge necessary for effectiveness in the clinical setting and that what differentiated them in terms of clinical performance was in large part related to differences in their emotional intelligence competencies—specifically, their Self-Management competencies. This does not minimize the role of knowledge in dental students’ effectiveness in the clinical setting, but it does point to the important role that emotional intelligence competencies may play in enabling dental students to excel in the clinical setting. The major finding of this study—that emotional intelligence is a predictor of dental students’ clinical performance—has important implications for health professions education. First, the results should encourage other educational researchers in the health professions to examine the role of emotional intelligence in student performance. Second, as evidence for the role of emotional intelligence in health professions student and practitioner effectiveness April 2013 ■ Journal of Dental Education accumulates, curriculum designers should consider implementing and evaluating components designed to help students develop emotional intelligence competencies. Health professions students invest a great deal of time, effort, and financial resources in their training. It is the responsibility of educators, then, to equip them in the best way possible. It is increasingly clear that this means not only providing knowledge, but helping students to develop the competencies they will need to best serve their patients and to prosper in their chosen careers. Finally, these findings may have implications for the health professions admissions process in the future. Educators have discussed the possibility of including consideration of ratings of applicants’ emotional intelligence in the admissions process,41-43 but this prospect must be approached with caution. Emotional intelligence in the health professions is a relatively new line of inquiry. Additional work will be required to confirm and elaborate the role of emotional intelligence in health professions student and practitioner performance. In addition, an easily administered, valid, and reliable instrument must be available to measure applicants’ emotional intelligence. Currently available measures of emotional intelligence were not developed for use in the admissions process. For example, the ECI-U was developed for developmental and research purposes and was not designed for use in administrative decision making.32 Although it is likely that current instruments could be adapted for use in the admissions process, more study will be required to establish the predictive validity of the instruments for this purpose. REFERENCES 1. Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching medicine as a profession in the service of healing. Acad Med 1997;72:941-52. 2. Ozar DT, Sokol DJ. Dental ethics at chairside: professional principles and practical applications. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994. 3. Emmerling RJ, Goleman D. Emotional intelligence: issues and common misunderstandings, 2003. At: www. eiconsortium.org/reprints/ei_issues_and_common_misunderstandings.html. Accessed: June 19, 2006. 4. Goleman D. Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books, 1998. 5. Goleman D. An EI-based theory of performance. In: Cherniss C, Goleman D, eds. The emotionally intelligent workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001. 6. Goleman D, Boyatzis RE, McKee A. Primal leadership: realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002. 7. Gerbert B, Bleecker T, Saub E. Dentists and the patients who love them: professional and patient views of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 1994;125:264-72. 425 8. Kulich KR, Ryden O, Bengtsson H. A descriptive study of how dentists view their profession and the doctor-patient relationship. Acta Odontol Scand 1998;56:206-9. 9. Stratton TD, Elam CL, Murphy-Spencer AE, Quinlivan SL. Emotional intelligence and clinical skills: preliminary results from a comprehensive clinical performance examination. Acad Med 2005;80:S34-7. 10.Borges NJ, Stratton TD, Wagner PJ, Elam CL. Emotional intelligence and medical specialty choice: findings from three empirical studies. Med Educ 2009;43:565-72. 11.Todres M, Tsimtsiou Z, Stephenson A, Jones R. The emotional intelligence of medical students: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Med Teacher 2010;32:42-8. 12.Carr SE. Emotional intelligence in medical students: does it correlate with selection measures? Med Educ 2009;43:1069-77. 13.Arora S, Ashrafian H, Davis R, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Sevdalis N. Emotional intelligence in medicine: a systematic review through the context of the ACGME competencies. Med Educ 2010;44:749-64. 14.Talarico JF, Metro DG, Patel RM, Carney P, Wetmore AL. Emotional intelligence and its correlation to performance as a resident: a preliminary study. J Clin Anesth 2008;20:84-9. 15.Taylor C, Farver C, Stoller JK. Perspective: can emotional intelligence training serve as an alternative approach to teaching professionalism to residents? Acad Med 2011;86(12):1551-2. 16.Weng HC, Steed JF, Yu SW, Liu YT, Hsu CC, Yu TJ, Chen W. The effect of surgeon empathy and emotional intelligence on patient satisfaction. Adv Health Sci Educ 2011;16:591-600. 17.Weng HC. Does the physician’s emotional intelligence matter? Impacts of the physician’s emotional intelligence on the trust, patient-physician relationship, and satisfaction. Health Care Manage Rev 2008;33(4):280-8. 18.Beauvais AM, Brady N, O’Shea ER, Griffin MTQ. Emotional intelligence and nursing performance among nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2011;31:396-401. 19.Smith KB, Profetto-McGrath J, Cummings GG. Emotional intelligence and nursing: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Studies 2009;46:1624-36. 20.Pau A, Rowland M, Naidoo S, AbdulKadir R, Makrynika E, Moraru R, et al. Emotional intelligence and perceived stress in dental undergraduates: a multinational survey. J Dent Educ 2007;71(2):197-204. 21.Hannah A, Lim BT, Ayers KMS. Emotional intelligence and clinical interview performance of dental students. J Dent Educ 2009;73(9):1107-17. 22.Azimi S, AsgharNejad AA, Kharazi Fard MJ, Khoei N. Emotional intelligence of dental students and patient satisfaction. Eur J Dent Educ 2010;14:129-32. 23.Ranney RR, Wilson MB, Bennett RB. Evaluation of applicants to predoctoral dental education programs: review of the literature. J Dent Educ 2005;69(10):1095-106. 24.Gray SA, Deem LP, Straja SR. Are traditional cognitive tests useful in predicting clinical success? J Dent Educ 2002;66(12):1241-5. 25.Park SE, Susarla SM, Massey W. Do admissions data and NBDE Part I scores predict clinical performance among dental students? J Dent Educ 2006;70(5):518-24. 426 26.Smithers S, Catano VM, Cunningham DP. What predicts performance in Canadian dental schools? J Dent Educ 2004;68(6):598-613. 27.Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental education programs. At: www.ada. org/sections/educationAndCareers/pdfs/predoc.pdf. Accessed: December 14, 2011. 28.Boyatzis RE. Competencies as a behavioral approach to emotional intelligence. J Management Dev 2009;28(9):749-70. 29.Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P. Selecting a measure of emotional intelligence: the case for ability scales. In: Bar-On R, Parker JDA, eds. The handbook of emotional intelligence: theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000. 30.Bar-On R. Emotional and social intelligence: insights from the emotional quotient inventory. In: Bar-On R, Parker JDA, eds. The handbook of emotional intelligence: theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000. 31.Boyatzis RE. The competent manager: a model of effective performance. New York: John Wiley, 1982. 32.Sala F. Emotional competence inventory (ECI) technical manual. Boston: Hay Group, 2002. At: www.eiconsortium.org/measures/eci_360.htm. Accessed: June 26, 2006. 33.American Dental Association, Department of Testing Services. Dental admissions testing program user manual, 2005. At: www.ada.org/prof/ed/testing/dat/datusermanual. pdf. Accessed: May 19, 2006. 34.Boyatzis RE, Sala F. Assessing emotional intelligence competencies. In: Geher G, ed. Measuring emotional intelligence: common ground and controversies. New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2004. 35.Christakis DA, Feudtner C. Temporary matters: the ethical consequences of transient social relationships in medical training. JAMA 1997;278:739-43. 36.Sherman JJ, Cramer A. Measurement of changes in empathy during dental school. J Dent Educ 2005;69(3):338-45. 37.Victoroff KZ, Hogan S. Students’ perceptions of effective learning experiences in dental school: a qualitative study using a critical incident technique. J Dent Educ 2006;70(2):124-32. 38.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA 2002;287:226-35. 39.Wagner PJ, Moseley GC, Grant MM, Gore RJ, Owens C. Physicians’ emotional intelligence and patient satisfaction. Fam Med 2002;34:750-4. 40.Gotler RS, Barzilai DA, Kikano GE, Stange KC. Does health habit advice affect patient satisfaction? Prev Med 2001;33:595-9. 41.Sefcik DJ. Attention applicants: please submit emotional intelligence scores. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2005;105:401-2. 42.Elam CL. Use of emotional intelligence as one measure of medical school applicants’ noncognitive characteristics. Acad Med 2000;75:445-6. 43.Cadman C, Brewer J. Emotional intelligence: a vital prerequisite for recruitment in nursing. J Nursing Management 2001;9:321-4. Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 77, Number 4

© Copyright 2026