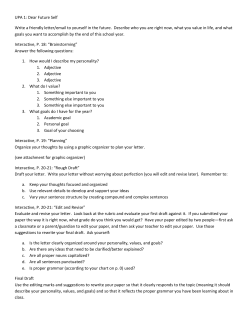

Establishing explicit perspectives of personality for a sample of by